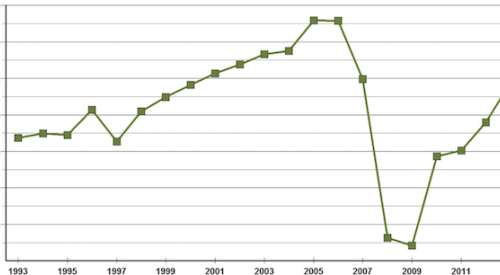

It’s a classic story about an immigrant in America who, through hard work and force of will, begins with next to nothing and creates a great firm. In this case, Orleans Homebuilders grew to build 2,300 units at its peak in 2006 with just short of a billion dollars in annual sales, ranking No. 42 on Professional Builder’s list of Housing Giants. Then came the devastation of the U.S. home building industry, which began in 2006 in some markets, picked up steam in 2007, accelerated in 2008, and became a veritable juggernaut in 2009. By 2010, the housing recession had taken down half the builders in America. Orleans joined those unenviable ranks in 2010, shedding assets and employees, culminating in a Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing, which saw the last of three generations of the Orleans family depart the firm. Although Orleans was in good company, what accounted for the demise of this 90-year-old institution when many of their competitors managed to work through the crisis and survive? And how did Orleans manage, against tremendous odds, to come back?

History

A.P. Orleans, a Russian immigrant, built and sold his first homes in northeast Philadelphia in 1918 and grew over the years to become a significant player in the Philly market. Marvin Orleans, A.P.’s son, led the company as they developed into a major builder in Philadelphia and South Jersey. Seeing even greater opportunities beyond their immediate environs in the early ‘70s, Orleans formed FPA Corp., and entered the Florida market as a public company traded on the American Stock Exchange. FPA built thousands of Florida homes primarily in the Pompano Beach area, including the Palm-Aire Resort and Country Club. Also under the FPA umbrella, the company opened Newtown Grant, the largest planned community in Bucks County, Pa. Beginning in 1985, after a 13-year legal battle over density, zoning, and entitlements, Newtown Grant developed into a community of 1,750 single-family homes, condominiums, and townhouses with recreational facilities.

All the while, Orleans Homebuilders remained privately held and continued to grow in its Pennsylvania and New Jersey markets, including Larchmont in Mount Laurel, N.J., a community of more than 10,000 homes plus shopping centers and office space built over two decades. When Marvin Orleans died in 1987, founder A.P.’s grandson Jeffrey Orleans took the helm of both FPA and Orleans. Shortly after, FPA left the Florida market. In 1993, the two companies were merged into FPA Corp., then changed the name to Orleans Homebuilders (OHB), a public company listed on the AMEX.

Orleans remained focused on its Pennsylvania and New Jersey core markets until 2000 when it expanded into Richmond and Tidewater Virginia along with Charlotte, Raleigh, and Greensboro, N. C., by acquiring Parker & Lancaster. The acquisition of Peachtree assets in 2004 expanded the Orleans presence in Charlotte. In 2003, the company returned to Florida entering the Orlando market by buying Masterpiece Homes, followed by a move west to Chicago with the acquisition of Realen Homes. In December 2005, Orleans entered the Phoenix market through a start-up that acquired two tracts of land for development. Orleans did not build any homes in the Phoenix market, however, and ultimately disposed of its Arizona assets at a substantial loss in December 2007 as the U.S. housing markets began to show real stress.

At its height in fiscal year 2006, the company delivered a well-diversified 2,303 homes with deliveries in Florida and the North, South, and Midwest regions. Revenue that year topped out at $975 million, with a stock price of $32 per share. To fund acquisitions, Orleans used a $650-million revolving credit line and issued trust preferred securities in the amount of $105 million with a secondary offering of $200 million priced at $24.75 per share. This was a company seemingly on its way to a top-10 ranking and, at least to the outside world, a builder to be reckoned with on the national scene, sure to pass $1 billion in sales the following year. But it was not to be.

Like many other home builders, Orleans was dealt a severe blow by the housing market collapse, resulting in their Chapter 11 filing in 2010. With a few years of hindsight and a fresh perspective, Larry Dugan, long-time Orleans executive vice president of land and general counsel, sums up the following key reasons for the bankruptcy filing:

1. Orleans was leveraged to the point of losing the ability to weather any market downturn.

2. Some expansion investments were ill-advised, such as the $60-million acquisition of Realen in Chicago followed by the $30 million in Phoenix land purchases, sold at a huge loss without producing a single unit.

3. Banks were in poor shape, feeling tremendous pressure to abandon real estate in a hurry and showing little patience or flexibility. During this time Wachovia, Orleans’ primary source of capital, was taken over by Wells Fargo.

4. Changes in leadership in 2009 contributed to a period of uncertainty.

5. Executive leaders changed product “weekly and sometimes daily,” creating a custom home operation with no connection among the floor plans, scopes of work, and specifications with the base house and option budgets.

6. Orleans became focused on generating cash leading up to and during bankruptcy. This practice created a culture of building spec homes with all the best options, and then offering huge discounts to move the units. The sales organization learned to discount in order to sell while Realtors become conditioned to Orleans negotiating all offers and routinely accepting low-balls. These habits impacted margins and appraisals and, more importantly, made it okay to lose money.

7. A lack of cash also impacted field morale, resulting in messy homes, sloppy job sites, and declining sales.

Rebirth

After the 2010 bankruptcy filing, several hedge funds acquired the distressed debt of the company and eventually converted the debt to equity and led the reorganization process. Contrary to popular expectations of Gordon Gekko-style management, the hedge funds, which prefer to be called sponsors, saw restarting the company as a viable alternative to merely selling the assets in a piecemeal fashion. This gave 150 experienced employees a second chance. The hedge funds syndicated a new term-loan to provide sufficient capital to operate and grow the company and established a new board with three outside directors.

Perhaps the most tangible outcome of the newly capitalized structure is the repositioning of the land owned and controlled by the new Orleans. “Over the last 24 months, Orleans has repositioned its operations in North Carolina, Illinois, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania to focus on first move-up, multi move-up, and active-adult buyers. Today, 33 percent of our sales come from communities we didn’t even own in 2011, and these new communities, along with repositioned legacy communities, are delivering margins averaging 800 bps better than when the company exited bankruptcy,” Dugan says.

Transition

Orleans executive team members, left to right: Trish Grayauskie, Vice President of Human Resources; Lee Darnold, Executive Vice President, Operations; Alan Laing, Chief Executive Officer; Gray Shell, Chief Financial Officer; and Larry Dugan, Executive Vice President, Land

Veteran industry executive Alan Laing took the helm as Orleans’ chief executive officer in November 2012, replacing George Casey who after leading the firm through the initial post-bankruptcy period was ready to move on. According to Laing, the recovery was not without pain. Sponsors and new executives alike underestimated how broken the systems and core processes were and the lasting impact of bankruptcy on the culture of the company. The employees who endured the process became survivors more than active participants in the recovery. Suppliers and trades were reluctant to engage with the new company based upon troubles of the past.

“This has been my leadership lesson of a lifetime,” Laing says. “The long upward run of the last housing cycle created successful companies that believed it was the quality of their strategy that created the large profits … meanwhile they forgot the fundamentals of running a good business. I wrongly assumed basic operating procedures were in place and the employees had fundamental experience, training, and skills to operate the everyday process of sales, starts, construction, closing, and warranty at an industry-standard level.”

With a fresh senior leadership team in place and fresh talent in the field at the division president and functional leadership levels, Orleans Homes tackled each operational issue with renewed vigor. “What I am most proud of at this point,” Laing says, “is the number of new leaders, combined with veteran talent that have delivered on aggressive plans over the last 18 months. 2013 was a year of reaping the benefits of what was sown and cultivated through hard days from 2011 on.” When asked what was most helpful in making the transition from a builder best known for its recent bankruptcy to a high-performing home builder, Alan describes an interesting journey. Here are his key takeaways:

• The value of leadership and talent. My experience at Pulte taught me that playing a major league sport takes major league talent. We have successfully rebuilt our talent base at every level, hiring from the very best public and private competitors. This has not been simple or easy, but the downturn impacted all companies and some high performers are simply fatigued from working for one company for a long time. They are interested in being part of something new, fun, and challenging and, more than anything, feeling like they make a difference.

• The hedge funds are an incredible asset. Despite public opinion our sponsors have been very helpful. They are extremely smart, experienced business people. They challenged me and our team to improve and take calculated risks. To a person, they have been fun and stimulating to work with.

• We invited our suppliers and trades to become involved in our business. They participate in the value-engineering of our plans, help define and implement online scheduling tools, provide feedback on what’s working and what needs our attention, and have shown patience while we work through our challenges. They have also helped identify top talent and in some cases helped us recruit them. We now do business with the vast majority of Orleans’ long-term trades. It took time to rebuild confidence, but it has been worth it.

A New Orleans

Alan Laing describes a remarkable mix of new management in the company with diverse backgrounds and strengths. Division presidents include former high-level stalwarts from NVR, Lennar, and Pulte, among others, with both land and financial backgrounds. Senior management in the home office includes Orleans veterans plus experienced hands from Centex, Lennar, NVR, and Pulte as well as strong players procured from such notable outside-the-industry firms as Bose and Nokia. Laing calls their selection criteria “basic”:

1. Proven performer

2. Willingness to work very hard

3. Willing to stand up for their beliefs

4. Deep appreciation for front-line employees and desire to selflessly support their success

5. Belief that customer satisfaction and quality are the core brand platform for all good businesses—especially home building

6. Looking for an adventure and not afraid to take risks

Whether you call those criteria merely basic or genuinely inspired, Orleans appears to have assembled a high-caliber team to lead the comeback. Not everyone left the company, Laing explains. “We have several holdovers in key roles. To a person they made it clear to me they wanted to be a leader in our transformation; they had more to offer; they felt our story was not finished, and our best days were ahead. They are key to our success and help us respect the positive parts of our history as well as provide the energy to create a better future.”

With the company now on an even keel, where do they go from here? Now building traditional single- and multi-family products in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York markets as well as Chicago, Raleigh, and Charlotte, Laing explains that they will restrict growth to those markets only “until we reach dominant market share in our targeted segments and submarkets.”

Orleans is hardly the first builder with a goal, as Laing describes, “to provide well-located communities, modern and fun to live in homes with great quality and customer satisfaction.” But Alan’s considerable experience leads him to define the means a bit differently than most home building executives. “We are guiding the Orleans culture to become the employer of choice for employees, suppliers, and trade contractors. We strive to create an expanded ‘culture of inclusion’ with all stakeholders—a team and performance-driven culture where all can learn, grow, and make a difference.” And the money? Laing is clear that top-quartile financial performance is a must to provide the required returns for Orleans shareholders. In their last fiscal year ending June 2013, Orleans grossed $192 million on 526 closings and projects $225 million on 628 units for the current fiscal year ending June 2014.

Summing up, Laing is quick to state the Orleans team has made many mistakes over the past two years, but that they are all learning together. “Our key performance measures are all improving. Sales, margins, quality, and customer satisfaction are all up significantly and are at commonly accepted industry standards. Our employees have been the difference; they have risen to the challenge and taken ownership for our continued success. They deserve the majority of the credit for our improved performance. Furthermore, we have taken some outstanding land positions, and have set the business up to continue to grow over the next few years.” Are the hedge fund sponsors happy? Laing replies with an emphatic “Yes!” Then adds, “Well, as happy as hedge funds get.”

The great housing industry crash took a tremendous toll in companies lost, fortunes squandered, and the decimation of the lives of people from many walks of life. So many of the money changers took the easy way out, shutting builders down and liquidating assets for what little they could. Orleans serves as a compelling example of how, with the visionary support of a few financiers, an inspired management team, and the willingness of a dedicated core group of employees to carry on, a home builder can resurrect itself from the dead. A hopeful message, and a fitting one for this time of year. PB