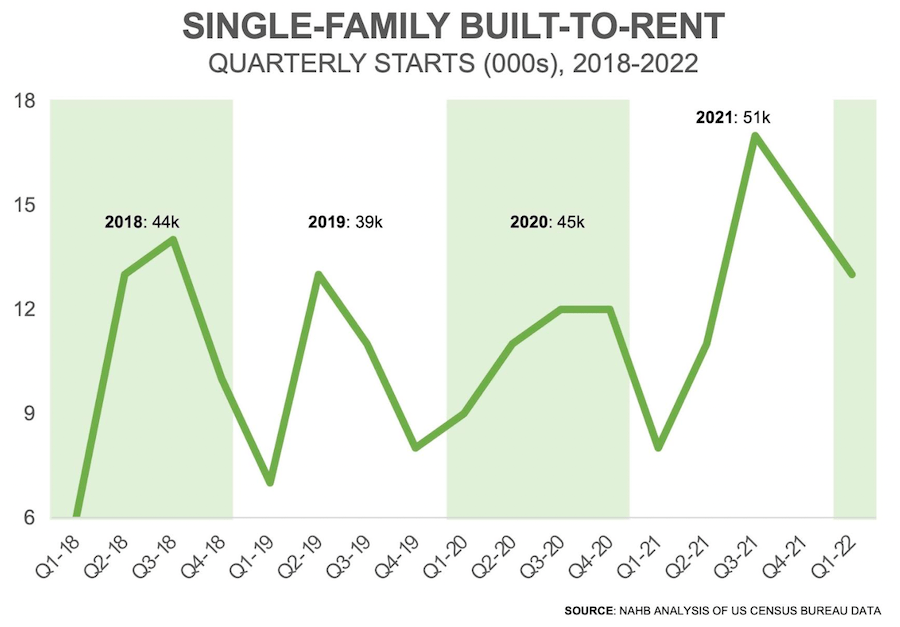

Since 2017, builders started an estimated 190,000 single-family built-to-rent (SFB2R) homes—about 64,000 of those in 2021 and in the first quarter of 2022, with all signs pointing upward.

That’s been enough of a sustained blip on the radar to garner attention not only within the housing industry but among consumers, the general news media, and investors—the latter pouring $45 billion into the segment in 2021, according to John Burns Real Estate Consulting (JBREC), which currently counts more than 560 SFB2R communities in its database, 27% of which were built within the previous two years.

In the fourth quarter of 2021, the National Rental Home Council (NRHC), in Washington, D.C., reported that new construction accounted for 26% of properties added to the portfolios of single-family rental home providers, compared with just 3% in the third quarter of 2019.

For now, the hype about built-to-rent appears to match the reality, and its future is being described in equally rosy terms, such as “blue skies,” “incredible runway,” and “here to stay” by home builders, developers, investors, property managers, and other market watchers.

“The historic model for building and selling homes is no longer sufficient,” says David Howard, executive director of NRHC. Built-to-rent, he says, “brings a new supply of homes online, which is something we haven’t seen in this space for a while.”

Single-Family Built-to-Rent Still in the Early Stages

With so much buzz, it’s easy to forget that the SFB2R market is still relatively new to the arena ... and pretty small compared with, say, the 460,000 multifamily units started last year.

“It’s the Wild West out there, and headlines can make it look a lot bigger than it actually is,” says Mitchell Rotta, senior managing director, Build-For-Rent at TruAmerica Multifamily, which last February launched a B2R development division to build townhome and single-family rental communities in suburban submarkets.

Through its database, JBREC estimates there are 15 million single-family rentals scattered across the U.S., from individual existing homes (the traditional model and vast majority of the segment) to entire communities (the new model). “We’re still in the early stages,” says Don Walker, the firm’s president of strategic planning and forecasting. He asserts that the segment isn’t so much expanding the housing market as it is “shifting demand” from existing homes and apartments.

Attempting to nail down actual new SFR home construction, though, is elusive. While the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) arrived at 51,000 SFB2R starts in 2021 by analyzing Census data, apartment search website RentCafe’s take on data from its sister company Yardi Matrix estimates that 6,740 new built-to-rent homes were completed last year and another 13,900 are about to hit the market.

Then there’s Hunter Housing Economics’ 2022 forecast of at least 110,000 B2R housing starts, including single-family detached, townhomes, and so-called “horizontal multifamily”—one-bedroom units with common walls. That’s about 6% of the projected 2.1 million housing starts this year and nearly twice the number of units NAHB estimated were built in the last 12 months through March.

A Reality Check for Single-Family Built-to-Rent?

But what about the segment’s long-term future when the white-hot hoopla eventually recedes?

The answer depends on several factors, such as whether large institutional owners (which currently control only about 2% of existing and new rental homes, including apartments and one-off single-family units) and production builders and community developers see the sector as a short- or long-term play.

Right now, the market is skewed by players eager for a quick return on investment enabled by high-volume production and demand from an increasing number of consumers who can’t afford homes or who choose to rent. That frenzy is causing some to overpay for land and enter markets without the requisite knowledge.

“Capital tends to follow capital, but you don’t have $85 billion in expertise out there behind the capital,” cautions Chris Bley, co-president and chief investment officer for residential investment firm IHP Capital Partners. He’s quoting a figure that Alan Ratner, managing director at housing sector research firm Zelman & Associates, gave in a Bloomberg article published earlier this year. IHP is currently an investment partner with Arizona-based TerraLane Communities, a developer of luxury single-family rental homes, and is looking to back other builders and developers in the space.

RELATED: MORE 2022 HOUSING GIANTS ARTICLES AND DATA

- Housing Giants 2022: What Now? The Housing Industry Post-Pandemic

- Housing, Industrialized: Marketing Industrialized Construction to Consumers

- 2022 Housing Giants List: U.S. Home Builder Rankings by 2021 Revenue and Closings

- 2022 Housing Giants rankings by housing type and region

He adds that SFB2R “is still a residential play, but a lot of people don’t understand the ‘build’ part of it.” In their pursuit of this particular golden goose, he says, “some ducklings could get run over,” meaning investors charging ahead without a builder wingman to guide them.

The presence of well-managed and capitalized operators would ideally force all players in the B2R space to up their game when it comes to financing, leasing, marketing, production, property management, and maintenance. “You have to be able to do all of these things well,” says Steven LaTerra, CEO of TerraLane Communities, which is seeking developers and general contractors as strategic partners to fill in some of those blanks.

Other factors that will help shape (or sour) the sector’s sustainability as a worthwhile multiyear investment include land availability, rent-to-income ratio escalations, and adequate SFB2R community and property management and maintenance services ... and the money to continue servicing them at a level that keeps rents high and vacancies low.

The locations of new SFB2R communities are of particular concern to Mark Wolf, founder and CEO of San Antonio-based AHV Communities, which has 16 communities and 2,100 homes under its “Built-For-Rent” trademark. “Too many investors and developers are going to the farthest outskirts of markets to purchase inexpensive land, almost blindly,” he says. “There’s a rush to buy anything they can get their hands on, and that’s a recipe for disaster.”

Respecting the Risk in B2R

Vertically integrated, from land acquisition through property management and maintenance, AHV strives to find and build in what Wolf deems “A-plus” locations, creating highly amenitized communities with clubhouses, pools, dog parks, and other features found in for-sale developments—the key hedge, he says, against declining value over time. His company also looks at a 10-year ownership window for its properties. After that, it may sell, refinance, or hold an asset.

NexMetro Communities, celebrating its 10th year in SFB2R, has a similar view. The Phoenix-based company started out as a merchant builder, “but now the sector is more of a long-time hold for us,” says Jacque Petroulakis, EVP for marketing and investor relations.

As of March 2022, NexMetro had 42 for-rent neighborhoods with 6,755 homes either completed or under construction and is expanding into several new markets this year, including Austin, Texas, and is searching for opportunities in secondary markets where values may not be as high but there’s still demand, she says.

Other sources agree that long-term players are more likely to be sector winners. “Right now, if you have [the asset] and can sell it, you do it. And we’re looking for opportunistic returns,” says IHP’s Bley. “But we also like the idea of building and holding.”

Finding land and construction labor when both are scarce and expensive for any type of construction also could put a crimp in the B2R dreams of investors, developers, and builders.

“The historic model for building and selling homes is no longer sufficient.”

—David Howard, executive director, National Rental Home Council

TruAmerica’s Rotta, who lives in Phoenix, says that market’s contractors are already stressed out trying to keep pace with building permits that he says fall far short of meeting demand for for-sale and for-rent houses. (It’s one reason that Invitation Homes, a real estate investment trust [REIT] with more than 80,000 SFR units across 16 markets in its portfolio, launched its Step Up, Stand Out program in partnership with SkillsUSA to bolster the pipeline of qualified tradespeople last fall.)

Others say the long-term outlook for SFB2R rests on the willingness of municipalities to accept an asset class for which relatively few have specific zoning allowances, or where NIMBYism against rental housing is palpable. (To help educate municipal officials, NRHC recently built a website, buildforrenthomes.com.)

However, some see the rental stigma abating. “This is the first time that people can rent a home they can be proud of,” says Sudha Reddy, founder and managing principal at Haven Realty Capital, in El Segundo, Calif. And he’s betting big on that premise: By mid-2023, he expects to double the value of Haven’s portfolio of 34 communities in nine states with about 4,500 homes valued at more than $1.1 billion.

Of course, all bets are off if a serious economic downturn hits the country. “We would expect that a recession accompanied by significant job loss would affect rental collections and certain operating metrics,” Reddy says. “We don’t see [a downturn] as something the industry can control, but participants will have to navigate through it.”

He’s also conscious of oversupply in some markets, hoping builders and investors will make sound judgments on where supply and demand are relative to an equilibrium scenario. “Avoiding a heavily oversupplied market will be important in the future,” he says, while adding, “there is nowhere near an oversupply situation anytime soon.”

It’s a familiar guessing game that many for-sale home builders and developers are applying to SFB2R. Consider Taylor Morrison, the nation’s sixth-largest home builder by revenue in our 2022 Housing Giants rankings. The company is now in its third year of a branding pact with Mesa, Ariz.-based Christopher Todd Communities to acquire and develop land and build rental homes.

Darin Rowe, the builder’s national president for build-to-rent, says that at the end of last year, Taylor Morrison had 20 projects approved, with five under development, in Austin, Dallas, and Houston, in Texas; in Phoenix; and in Orlando, Sarasota, and Tampa, in Florida, and intends to expand to other markets this year.

But he also concedes there’s not much construction going on in the built-to-rent sector yet, primarily because it takes between 12 and 18 months to get land entitled for this product, and another year to develop the land. He expects construction on these projects to begin sometime in 2023, counting on continued high demand by the time those homes are finished and ready to lease.

RELATED

- The Synergy of Industrialized Construction and Built-for-Rent Housing

- Are You Ready for Build to Rent?

- What’s Driving the Demand for Single-Family Rental Homes?

- Single-Family Rent Prices Are Surging to New Highs Across the U.S.

A Bullish Outlook for the SFB2R Sector

So far, those obstacles and potential hazards have neither slowed the sector’s growth nor diminished the exuberance for single-family rental homes among investors, developers, and builders.

In large part, that’s because the SFB2R product itself appeals to a broad mix of consumers, including Millennials, young families, and seniors—a growing number of whom rent by choice, say industry experts. And, as the average sales price of a new home continues to climb ($570,300 as of April, according to the U.S. Census Bureau) fewer folks are able to afford to buy a home, making the segment an increasingly essential element for attaining a single-family detached lifestyle.

That’s music to the ears of some of the country’s largest builders (and land owners and investors) eyeing SFB2R or engaging the sector more aggressively to fuel their growth and bottom lines.

Among those leading that charge is Lennar, the nation’s No. 2 builder among our Housing Giants, which provided details this past March about its intention to spin off three businesses—multifamily, land strategy, and SFB2R—into a separate operating entity. Its SFB2R business, called Upward America Venture (UAV), had $1.9 billion in assets at the end of the first quarter 2022.

With an equity commitment of $1.25 billion led by Centerbridge Partners, UAV will have access to Lennar’s 300,000 home sites and is positioned to acquire more than $4 billion in new single-family and townhomes from Lennar’s home building division and other builders.

Right now, the market is skewed by players eager for a quick return on investment enabled by high-volume production and demand from an increasing number of consumers who can’t afford homes or who choose to rent.

“Smart people figured out that it was better to sit on land with houses on it because the return on rentals is almost as good as for-sale housing right now,” says George Casey, president and CEO of Maine-based consulting firm Stockbridge Associates, which consults with several production home builders.

Sometime this year, PulteGroup (the No. 3 Housing Giant) is expected to start delivering homes to Invitation Homes as part of the builder’s five-year strategic agreement to supply the REIT with 7,500 single-family houses for rental purposes.

A spokesperson for Invitation revealed that communities in Texas, Georgia, Southern California, North Carolina, and Florida will be the first to receive those homes from Pulte. She also adds that Invitation is working with other builders to help the REIT break ground on new for-rent communities.

Tricon Residential, a Canadian real estate company that owns about 31,000 rental properties across North America, is certainly bullish on SFB2R. In a 60 Minutes segment aired earlier this year, president and CEO Gary Berman revealed the company’s goal to acquire 18,000-plus SFB2R homes from regional and national builders across the Sun Belt within a three-year period, leveraging a $5 billion joint venture it formed with three institutional investors last July. It also plans to build 3,000 such units by 2024.

Multifamily 2.0?

Several developers and builders see SFB2R as a complementary piece of a larger strategy that “meets our customers on their housing journey,” says Rowe, including master plans that incorporate single-family rentals among for-sale homes, perhaps even side by side. One model for this strategy, suggests NRHC’s Howard, is Tricon Residential communities that include SFR, multifamily apartments, and entry-level and move-up for-sale houses.

Other builders and developers are following a similar path. Taylor Morrison’s 251-unit for-rent product for Christopher Todd Communities in Lavon, Texas, is part of the Elevon master plan that encompasses 4,500 single-family homes, 1,000 multifamily units, an 80-acre business park, and 100 acres of mixed-use retail.

TruAmerica Multifamily’s approach to B2R, says Rotta, is to create “mini master plans” with both for-rent and for-sale housing. Of the five deals in the company’s current pipeline poised to produce nearly 1,200 houses, three include for-sale homes.

With that, Richard Ross, CEO of Quinn Residences, an Atlanta-based owner/developer that entered the fray in 2020, believes institutions will steadily control more of the SFB2R market—a scenario he half-jokingly calls “Multifamily 2.0” because, he says, it’s just a matter of time before big operators in the apartment arena, such as Avalon-Bay Communities, Equity Residential, and Mid-America Apartment Communities, see the segment as a fat pitch in their strike zones.

For other SFB2R developers and builders, the sector reinforces a more traditional rent-to-buy progression. Case in point: In February, Invitation Homes became the lead investor in Pathway Homes, a new company that works with renters to purchase their homes outright.

Within four or five years of living in its rental homes, 30% of Tricon’s tenants buy a house. Earlier this year, the company launched Tricon Vantage, a program aimed at providing tenants with the tools and resources to set financial goals and enhance their economic stability. As part of Vantage, Tricon intends to launch a resident down-payment assistance program in the third quarter of this year, rewarding long-term residents in good financial standing.