Changing the Rules New Models Praise Versus Punishment More Information

Ask any builder to list the obstacles to innovation, infill construction and transit-friendly communities and local zoning restrictions likely will rank near the top of the list, along with legal liability and land costs.

That could change. Many planning experts, both in the academic world and in the field, believe that traditional zoning must be — and will be — completely transformed.

Art Lomenick, president of Trammell Crow's High Street Residential subsidiary in Dallas, for example, says states and municipalities already have recognized the limitations of conventional zoning.

"One of the main things we do is work with public-private partnerships," Lomenick explains. "I'm seeing changes all the time. The really smart municipalities have done comprehensive plans that are multi-modal, and they're rapidly moving away from [traditional zoning]."

Replacing zoning means offering something better in its place, such as state, county or municipal comprehensive plans. But as economist and attorney Aaron Gruen of Gruen Gruen + Associates in Deerfield, Ill., points out, those plans can go wrong if they're based on opinion and not hard research.

"Everywhere we work, between Chicago and Southern California," he says, "we've seen a tendency for comprehensive plans to be based on individual rather than community-wide concerns."

Gruen explains that because local government doesn't have "checks and balances" the way the federal government does, development plans may be produced by small groups using arbitrary criteria instead of objective measures — such as the best way to boost the tax base or minimize maintenance over the long haul.

"Planning can be very faddish," he says. "For example, pedestrian malls were the big craze, but we never got into those. It's hard to make the numbers work. You have to look at objective measures — such as how setbacks will impact maintenance. For example, one of our [city] clients had changed setbacks [on the comprehensive plan] to provide more greenspace. But they didn't calculate the added costs of maintenance for residents. As a result, people stopped doing maintenance, and the neighborhood got worse and worse."

In other words, without careful analysis, even well-intentioned planning can simply codify inefficient zoning.

"If a municipality doesn't get it," Lomenick says, "If they don't understand good planning, we can't really help. It takes too long to educate them. But there's really no excuse for not getting up to speed, now that it's so easy for these municipalities to get information."

Zoning, instead of encouraging greater density or transit-oriented housing, frequently undercuts efforts to use land more efficiently and prevents mixed housing types. It also slows the permitting process to a crawl. How and when did zoning go astray?

"Most of the highest quality development in this country predates zoning," notes Brian Stone, assistant professor of city and regional planning at Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. "People like to say that sprawl is the product of unplanned settlement. But that's not the case. Every dimension of a suburban neighborhood is regulated (through local zoning)."

In the 1920s, Stone explains, city planners made rules aimed at keeping automobiles out of neighborhoods, for example, and created what later was adopted and changed into one of the familiar targets of smart growth — the dead-end cul de sac.

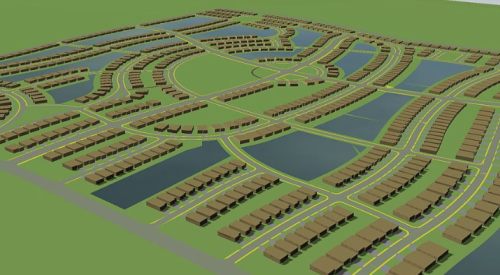

"We've been talking this way [about better ways of development] for a century," notes Emily Talen, professor and planning expert at the University of Illinois at Urbana—Champaign. "But planners kind of fell into a black hole in the 1950s and 1960s. Local zoning has not been a good thing for diversity. It has effectively separated people into housing 'pods.'"

Joseph Schilling, a land-use expert with the Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Va., says "Zoning's traditional framework did not address new issues, such as the exclusionary intent behind some ordinances; the process of developing large tracts of land; environmental and habitat protection; and the advent of suburban sprawl."

Stone says he entered his own field of research — regional heat zones — to test some of the claims of new urbanism as a more environmentally sound way to build. His work supports the need for zoning reform. "I've found that most of the claims about new urbanism's benefits are actually true," he notes. "For example, in Atlanta, the greatest increases in urban heat are caused by residential lawn areas. That's largely because (to meet zoning of lot sizes and setbacks), developers are cutting down so many trees. We could greatly reduce the impact simply by reducing lot size by 25 percent."

Urban planners and mid-size private developers increasingly find themselves on the same side of arguments for reforming localized zoning. But they still differ on one major planning point — who should spearhead efforts to reform the zoning landscape? Builders urge municipalities to take the lead. Planners argue that the building industry must change its ways.

Town planner Mary Madden of Ferrell Madden Associates in Washington, D.C., has described for the Urban Land Institute how private developers sometimes undercut efforts to replace zoning with broader form-based codes — even when those codes would likely streamline the permitting process.

"[Developers] often remain silent or even block the code's path," she observes, "if they are focused only on their current project rather than on the long-term vitality of the community."

Ed McMahon, a senior fellow at the Urban Land Institute in Washington, D.C., notes that builders have tended to "vastly oversimplify the idea of building what people want," rather than steering the market.

"A lot of it comes down to marketing," McMahon says. "That's the key to selling high-density, high-quality design, but a lot of the builder marketing we see is based on what was sold yesterday. For example, a builder will ask 'Which would you rather have: a small lot or a large lot?' when he could rephrase the question to say, 'Which do you care about more, having a big lot or living in a nicer neighborhood.' It's all about context. That's how you challenge NIMBYism."

Large production builders have been slower than mid-sized firms to take up the cause of zoning reform. It's not that they like the 9,000 different zoning jurisdictions in the U.S. — but it's the devil they know. Most already dabble in new urbanism and even high-rise construction, so they're well aware of those design principles. And the track record for this type of construction is still small. By some estimates, about 500 new urbanist projects have broken ground in the U.S. compared with tens of thousands of conventional plans.

Lomenick adds that builders will hesitate to spend their own capital to help cities restructure outdated zoning. They would rather set up shop where the hard work of reform has already been done.

"It's a municipality's job to change," Lomenick says, "But that's not easy. It means that local city council members have to make tough calls. For example, their budgets have to undergo a big shift. They have to stop spending on sprawl-oriented things like strip developments."

Lomenick says replacing old zoning laws with comprehensive plans grounded in research shouldn't be a hard sell for municipalities. Smart planning rests on solid financial ground.

"When you're in a higher density pattern, there's very little infrastructure to take care in terms of roads, trees to trim, water lines to maintain. If you're at five units per acre, you're screwed. But get up to fifteen units per acre, and you start seeing returns. Your property tax base actually starts producing money.

"The Leland group is a good example of somebody who is doing this," he continues. "They know how to run the numbers that private builders will be dealing with, and manage expectations. [Developers] must have help from municipalities to achieve affordable housing. There's no other way. And be clear. It's an investment, not a subsidy."

McMahon notes that although zoning was well intended, it has been built on a tradition of distrust — punishment rather than rewards. A good comprehensive plan, he says, emphasizes the reward side of the equation, which brings the responsibility back around to municipalities.

"Often, the only tool used in community planning is controlling density," McMahon notes. "But research shows that density has almost no impact on home values. In this area, around Washington, D.C., where are three highest priced areas to live in? Old Town, Chevy Chase and Alexandria. All of them are far denser than anything that zoning would allow us to do now. But people will pay to live in one of the most beautiful neighborhoods in the country."

Gruen notes that simply replacing zoning with a comprehensive plan may not improve the environment for construction, unless builder incentives are part of the picture.

"In many cases, the builder faces the same obstacles working on an infill site as he does on a greenfield," Gruen says. "But if your plan permits four-story homes instead of three on the infill site, all of a sudden the numbers work.

"Another thing that's not done enough is to give people trade-offs when developing the comprehensive plan rather than visual preference surveys," Gruen adds. "Most planners show a picture of Paris, then a weed-strewn field, and ask which type of place people like best."

Offering various trade-offs as part of the comprehensive plan, by contrast, lowers expectations, he says, and makes projects far more likely to get off the ground.

For example, although there's plenty of data from HUD and other organizations suggesting impact fees result in higher housing costs, we couldn't find any studies suggesting that builders have cut back on housing starts due to these fees. On the other hand, excessive zoning and permitting delays often have a direct impact on the number of projects a builder has underway.

Talen says the trade-off concept can be applied on other levels. If the city requires a certain percentage of affordable housing or green space, for example, developers can hand off that responsibility with a chunk of land.

"That's where something like a community land trust comes in," she says. "The private developer just hands over the land within the project, then the community land trust takes over. They screen people, and they build the homes. The developer avoids the headache altogether."

Several trends suggest that the iron grip of zoning on local land use is loosening. That doesn't mean that a wild west free-for-all will take its place. Instead, zoning will likely become an integrated part of "big picture" planning. Several promising trends, including form-based codes, mandatory enforcement of comprehensive plans and programs such as SmartCode are looking beyond prescriptive zoning.

Stone points out, that many of the "big ideas" about comprehensive planning never make it to the federal or even the state level of government. He asserts that some of the people with the most innovative ideas to reform our land-use patterns have very little political clout and status. But that, too, is changing.

"A lot of people are coming through planning schools now who want to be good developers," notes Stone. "They want to change the old myths with tools such as new urbanism."

Unlike Europe, Stone notes, the U.S. has no centralized planning authority — and a land-planning reform movement that is still small and largely driven by new urbanist architects and urban planners.

But Lomenick sees a shift in land planning that is already underway. Government at all levels is becoming interested, he says, and re-education of local planners is taking place at light speed, thanks largely to the Internet.

"I sat on some advisory groups with the HUD recently," Lomenick recalls. "They're coming up with a whole new lexicon. They're going to mandate planning that gets people out of their cars.

"This Federal process is always the last big oil tanker to move," he adds. "It has started with the small township, but success feeds on success, and there's a pretty tight fraternity of city conferences that are sharing ideas.

[Conventional] Zoning had its test, and it didn't test well," he says. "It will be gone in 10 years. People are smarter now. They want a lifestyle, not just a set of rules."

Changing the Rules

Arguments for ditching conventional zoning in favor of comprehensive planning can be supported by economic and demographic analyses. Although models and visualization remain important for "selling" a plan to residents, local planners need to focus on the numbers — and offer a range of "tradeoffs" that will lead to the best long-term financial, social and environmental stability for the region. Several studies conducted during the late 1990s using the most recent Census data show the benefits of "big picture" planning over localized rule making.

School-Age Children Per 100 Units of Housing| 20-plus Unit Apartments | 26.1 |

| Multifamily | 36.9 |

| Single Family Attached | 47 |

| Owner-Occupied Single Family Homes | 61.4 |

City planners concerned about the rising costs of schools can immediately see tax dividends gained by offering multifamily housing.

Source: HUD American Housing Survey, 1999

Projected Household Growth 2000–2010| Families without Children | 16% |

| Nonfamily Households | 14% |

| Families with Children Under 18 | -3% |

The writing is on the wall. Traditional families are on the way out, and new development patterns should match the demographic shift.

Source: 1996 U.S. Census Bureau

Number of Automobile Trips Daily (Average)| Single Family Detached | 10 |

| Apartment | 6.3 |

For obvious reasons, denser product types reduce traffic impacts on nearby roads, the opposite of what NIMBY neighbors might believe.

Source: Institute of Traffic Engineers, 1997

Annual Price Appreciation: Single-Family Homes Near Multifamily Structures| Not Near Multifamily | 2.66% |

| Near Multifamily | 2.90% |

| Near Low-Rise Multifamily | 2.91% |

| Near Mid-Rise Multifamily | 2.79% |

When multifamily housing joins single-family homes, property values tend to rise faster — a good reason to reform zoning rules that forbid mixed uses. These misguided rules, intended to protect property values, reinforce inaccurate stereotypes.

Source: American Housing Survey and NAHB, 1999 >

* Some of the above charts can be found in Urban Land Institute's "Higher-Density Development: Myth and Fact."

Three of the latest developments in regional planning promise a more streamlined regulatory environment than conventional zoning.

Alternative CodesSome municipalities now offer special codes that remove regulatory obstacles to entice developers into creating needed product. For example, the city of Spokane, Wash., has created an alternative code aimed at creation of more affordable housing. Builders who opt for this code are allowed to build using alternative construction techniques. The code also reduces parking requirements and offers density bonuses.

Form-Based CodesOriginally developed as a way to streamline greenfield development, form-based codes are becoming a tool for regional planning. Urban Land magazine describes them as a way to replace local zoning with more general "parameters" of construction so that local officials can create visionary plans. Unlike design guidelines, which many builders find too restrictive, form-based plans focus on the big picture: the building height; how close the structures are to the street; and windows and doors on walls facing streets and other public spaces. As an added benefit and selling point for buyers, "the uses within the individual structures are far less important than in conventional suburban configuration." Many regions have already used the new codes successfully, including Petaluma, Calif.; Saint Lucie County, Fla.; and Arlington County, Va.

SmartCodeOne of the most promising fast-track tools for streamlining municipal plans is now available in software form for a minimal fee. The SmartCode program, developed by Miami-based Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company, took about 10 years to put together and offers a turnkey method for municipal planners to adopt more progressive, comprehensive plans that can replace zoning.

Urban planners suggest that rewarding visionary development creates a win-win scenario for developers and towns, unlike traditional zoning. For example, charts such as this "healthy community index," which asseses the location of a planned development, demonstrate how a point system can be used to assess projects on their long-term value.

SIDEWALKS ON BLOCK

No (0 points) Yes (10 points)

PORTION OF LOCAL STREETS WITH SIDEWALKS.

Range from 0 points for no street within ½ kilometer have sidewalks up to 10 points for all streets have sidewalks.

PORTION OF LOCAL STREETS AND PATHS THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS.

Range from 0 points for no street within ½ kilometer with sidewalks that accommodate wheelchairs, up to 10 points for all streets with sidewalks that accommodate wheelchairs.

SCHOOL WALKABILITY

10 minus number of minutes required for a child to walk safety to school. 0 if walking to school is not feasible for a typical child.

CYCLING CONDITIONS

Portion of streets within 1 kilometer that safely accommodate bicycles,rated from 0 to 10.

NEIGHBORHOOD SERVICE DESTINATIONS

One point for each of the following located within ½ kilometer convenient walking distance, up to 10 maximum: grocery store, restaurant, video rental shop, public park, recreation center, library.

PUBLIC TRANSIT SERVICE QUANTITY

Number of peak period buses per hour within ½ kilometer, up to 10 maximum.

PUBLIC TRANSIT SERVICE QUALITY

Portion of peak-period transit vehicles that are clean and comfortable from 0 (all vehicles are dirty or crowded) up to 10 (all vehicles are clean and have seats available).

LOCAL TRAFFIC SPEEDS

Portion of vehicle traffic within 1-kilometer that have speeds under 40 kilometers per hour, from 10 (100%) to 0 (virtually none).

AIR POLLUTION

10 minus one for each exceedance of air quality standards.

Source: Victoria Transport Policy Institute (Canada)

Form-Based Codes: www.formbasedcodes.org

The Urban Land Institute: www.uli.org

SmartCode: www.dpz.com

Victoria Transport Policy Institute: www.vtpi.org