The primary role of a weather resistant barrier (also known as WRB, building wrap, or house wrap) is to protect the building envelope from bulk water, wind-driven rain, and water vapor. It is important that your WRB stands up against all three of these intruders. Within a WRB, there are three primary defense mechanisms: water holdout for bulk water, drainability for rain penetration, and proper permanence or breathability for water vapor.

Bulk Water Holdout

As its most basic function, a WRB must hold out water. A high-performance building wrap will be able to pass both “water ponding” tests, which measures a building wrap’s resistance to a pond of 1-inch water over two hours, and a more stringent hydrostatic pressure test where the material is subjected to a pressurized column of water for five hours.

Drainability

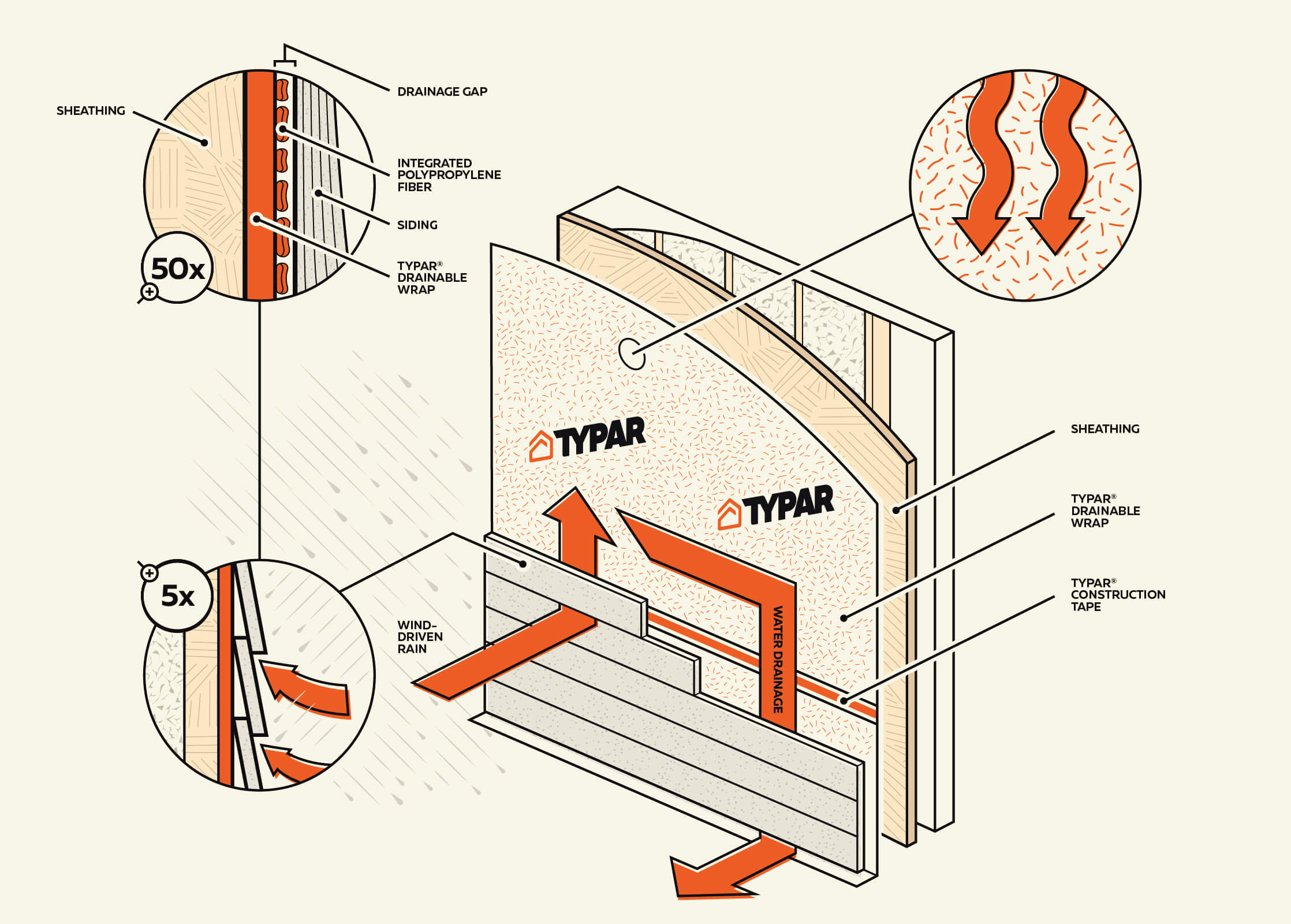

As the trend for tighter building assemblies continues to grow, building wraps have taken on a new function—removing trapped water from the wall assembly. The very latest innovations in housewrap technology are taking this moisture removal function one step further to also incorporate drainage capabilities.

The drainage efficiency of a building wrap is generally tested in accordance with ASTM E2273. Simply, this test involves spraying water onto a wall assembly and measuring its collection over time. However, given the variety of drainable building wraps available, how quickly bulk water is drained can vary significantly.

At the cutting edge of today’s building wrap technologies are new products that integrate drainage gaps into the material itself through creping, embossing, weaving, or filament spacers. These new products eliminate the need for furring strips, helping to reduce material costs and streamline installation.

These new drainable building wraps meet all current code requirements for drainage efficiency (ASTM E2273) without sacrificing the durability and ease of installation benefits builders and contractors have come to expect from premium building wraps. They are also vapor permeable, so moisture will not become trapped in the wall assembly and lead to mold or rot issues.

Permeance

A WRB must breathe to prevent moisture vapor from getting trapped in the wall cavity. Permeability measures the amount of vapor transmission that a building wrap will allow over a period of time. For a product to be considered a WRB and not a vapor retarder, International Code Council (ICC) mandates the permeance rating must be higher than 5 perms. There are a variety of ways permeability is achieved, and a higher perm rating doesn’t always equal a better building wrap.

“Inward Drive – Outward Drying,” a paper written by building scientist Joseph Lstiburek, recommends that specifiers aim for the “sweet spot” of 10-20 perms to achieve the desired balance of moisture protection and breathability. Achieving the optimal perm rating ensures that while water is prevented from entering the wall cavity, ideal levels of moisture vapor are still allowed to escape. He writes that too high, and the moisture driven out of the back side of the reservoir cladding into the air space will blow through the layer and the permeable sheathing and into the wall cavity. Too low, and the outward drying potential of the cavity is compromised. Thankfully, advances in building wrap technology are adapting to meet this need.

Fortunately building wrap technology, particularly using a “systems” approach, can help builders hit the sweet spot for permeance every time.

As the core component of the TYPAR Weather Protection System, the water holdout of TYPAR BuildingWrap is balanced, achieving a perm rating of 11.7, an optimal perm rating ensuring that while water is prevented from entering the wall cavity, ideal levels of moisture vapor are allowed to escape. This optimal breathability reduces the risk of standing water in wall cavities, which can potentially lead to mold growth and degradation of indoor air quality. For an added layer of performance, TYPAR BuildingWrap combines tear strength, UV stability, and the ability to withstand performance-robbing surfactants like oils, tannins, and soaps that can compromise an ordinary housewrap’s ability to block bulk moisture penetration.