Editor’s Note: The reporting and writing of this article was done months before the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting disruptions to the housing industry and the builders featured. We trust the information remains valuable, despite recent changes that may have occurred.

Succession planning has been a topic of conversation at the Rutt household ever since middle son Ben was 6 years old.

His father, Jeff, founded Keystone Custom Homes, in Lancaster, Pa., in 1992, and admits that Ben, now 30 and the company’s director of marketing, has acquitted himself well in every sales, purchasing, and marketing position he’s managed since joining Keystone six years ago. He would seem to be the heir apparent. Just not yet. “I’m 61, so it should happen sometime in the next 35 years,” Jeff says, laughing. Actually, he’s grooming Ben as the likely No. 1, presumably sooner than later.

The Rutts are a prime example of the housing industry, in which family-owned businesses are common and succession often comes from within. As far as timing is concerned, “Boomer owners are looking at options to sell now rather than go through another housing cycle,” says David Rosen, founder and president of Long Grove Capital, in Chicago, a mergers and acquisitions advisor to home builders. “Those who restarted or recovered after the Great Recession had a good run, but they’re ready to cash out.”

Lots of Options for Business Succession

The who and when of business (especially family business) succession gets complicated when an owner’s timetable for ceding control extends beyond what children or relatives waiting in the wings deem acceptable, leaving them champing at the bit. Another set of challenges arises when an owner chooses to sell the business to outsiders, which usually requires some financial and operational polishing to present the company’s best face to potential buyers.

An employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) is a kind of hybrid, in which ownership (family or otherwise) retains a measure of financial and management control, but offers employees equity (stock) ownership, a benefit plan that also has some tax advantages.

But succession planning of any sort remains an afterthought for too many private home builders. “The big mistake companies make is that they assume things will happen without putting together a game plan,” observes Chuck Shinn, a long-time industry consultant and president of Builder Partnerships, in Littleton, Colo.

So whether you’re an aging owner looking at your options or are in denial about how your company might carry on without you, consider how builders with recent succession experience got their companies and employees ready for the next step.

How Prepared Are You for Handing Off Your Business?

“We have several people who would be more than capable of stepping in if I decided to do something else,” says Pat Hamill, president of Oakwood Homes, in Denver, which he sold to Clayton Properties Group in July 2017.

At Keystone, Rutt says he actively encourages key managers—at weekly meetings and through writing exercises and reading—to think about how they would manage the company in good times or bad.

But sometimes management succession from within isn’t as clear or viable. Consider Robert and Karen Schroeder, co-owners of Mayberry Homes, in Lansing, Mich. Both are in their mid-60s and have been thinking about succession for a while. “I’ve been in the business since the late 1970s, and I’m ready to go,” Karen says.

Two of Bob’s sons work for the company, including Joe, in his 40s, who manages estimating and production. Two of Karen’s brothers are in the company, too, as is her daughter, Jodie, who handles sales, marketing, and model home setups. But Karen doesn’t think there’s any one employee ready to step in and run the entire show.

“The big mistake that companies make is that they assume things will happen without putting together a game plan.” Chuck Shinn, president, Builder Partnerships

“At this point, I see it being more of a team approach, with a few very talented employees leading various roles in the company,” she says. Any transition, though, remains uncertain, as Mayberry seeks to build its volume to 100 units this year and “get leaner without jeopardizing our integrity,” Karen says.

Tony Misura, founder of Misura Group, in Hudson, Wis., a succession plan consultancy, advises builder owners to start vetting the next generation of leadership for their companies at least a decade before they plan to exit. That diligence includes recruiting and mentoring younger talent, as Misura sees too many owners surrounded by what he calls “mini-mes,” which can become a self-inflicted risk if the owner suddenly gets sick or is incapacitated.

One of Jeff Rutt’s keys to succession success was requiring his sons to work for another organization for at least three years and earn at least one promotion before being considered for a job at Keystone. “That has paid huge dividends in building their confidence and the respect of the teams around them,” he says.

Todd Olthof, who co-owns Olthof Homes, in St. John, Ind., with brothers Scot and Fritz Jr., concedes that the next generation of leadership may be nonfamily members. Its management team already includes “a handful of people who could run things,” he says, and Olthof Homes continues to seek out bright, young talent.

Business Buyers Don’t Like Surprises

When owners start shopping their companies, they’re likely to encounter three buyer types, Long Grove Capital’s Rosen says. One type, such as Clayton, prefers keeping the seller’s management, including the owner, in place. The second type will ask the owner to hang around during the transition period. And the third type, Rosen says, “wants the owner gone, so it can put its own DNA onto the company.”

Shinn observes that while most buyers fall into the third category, there are recent exceptions, such as Century Communities’ 2018 purchase of Wade Jurney Homes, whose owner stayed on, and Clayton’s recent spate of acquisitions where the sellers’ leadership remained on board. “Clayton kept every promise and commitment they made,” says Hamill, specifically noting the synergy of both builders being dedicated to prefab construction.

Regardless of the buyer type, the quality of a builder’s financial performance is at least as important as its land position and the quality of its management when it comes to valuing the company for acquisition.

Bruce Werner, managing director of Kona Advisors, in Chicago, advises builders, before they think about selling, to perform a “quality of earnings” analysis that provides buyers with a clean balance sheet so they can assess a company’s performance and value over time.

And, at least to start, acquirers typically don’t want interruptions in the operations they’re buying, says John Wagner, managing director of 1st West Mergers & Acquisitions, in Cloverdale, Calif. “Succession planning means more than just keeping a few nameplates on C-suite doors,” he says. “It demands leaders remain in place to retain and integrate workplace culture, customer relationships, and vendor relationships, and to ensure continued success of the operation under new ownership.”

When Is a Successor ‘Ready’?

Timberlake Homes, in Annapolis, Md., is a classic example of how family-owned businesses get passed along.

John Minzer, Timberlake’s current owner and president, married the founder’s daughter and joined the company 41 years ago. In 2001, he and his brother-in-law, Frank Lucente, bought out Frank’s father through a 10-year tax-free payout. By 2008, Timberlake had $85 million in nonrecurring debt, and Minzer wanted to borrow more. Frank, who ran the renovation and custom-home division, balked. So Minzer bought him out under a structured agreement.

Minzer, now 66, comes into the office every day, and he plans to stick around for another five years before handing the reins to his 35-year-old son Jason through a similar buyout arrangement.

“It’s a rarity to find someone under 40 who is able to run a company.” John Minzer, owner and president, Timberlake Homes

Jason joined the company in 2007 as an assistant site manager, and is now Timberlake’s VP of construction and purchasing. But his father still thinks Jason needs more seasoning, especially on the financial side. “It’s a rarity to find someone under 40 who is able to run a company,” Minzer says. Even so, he points out, his son is already formulating a business model that would maintain Timberlake’s current production level of 100 to 115 homes per year with a greater focus on profitability.

Snyder Homes, in Shelburne, Vt., has a similar story. Before joining his family’s business in 2000, Chris Snyder cut his teeth working for a national builder in management positions in Texas and Florida. He was, he says, essentially running Snyder Homes from 2006 to 2011 when he approached his parents, Bob and Pat, about owning the company outright.

Over the next two years, the family, along with the company’s accountant and a trusted financial advisor, hammered out the details of that transition. Each of the company’s 17 LLCs was assigned an assessed value, and over a five-year period the parents would receive a portion of every home sale. Chris, 46, got the company into multifamily construction, and this year Snyder Homes expects to complete 120 apartment units and 48 single-family for-sale homes.

Setting Priorities for Business Succession

Snyder’s parents remain at arm’s length as board members. But it’s clear that other builders find it hard to let go.

Do they want to cash out? Preserve their legacy? Both? In March 2019, Keystone Custom Homes donated 89% of its nonvoting stock to the National Christian Foundation’s Charitable Trust. Rutt’s family retains 100% control of the company and accrues “major tax benefits” from that transaction, Rutt says.

The Olthof brothers, who bought out their father in 2012 through a six-year payout, are currently working with advisors on the next stage of their succession plan, which will take into account the different timetables of each brother. “We’re looking for flexibility so if one of us wants to take chips off the table, he can,” Todd Olthof says.

Karen Schroeder says that while she and her husband may consider selling Mayberry Homes if the right deal comes along, they also have four new pieces of land that, once developed, will set up the company for many years.

And Minzer, as he plots his company’s path, says he’s not exactly sure how succession would translate individually for his company’s 35 employees. “I haven’t figured that out yet.”

Succession: A Cautionary Tale

Mike Connor founded Connor Mill-Built Homes, in Middlebury, Vt., in 1969 to design and manufacture historical colonial reproduction house kits. In 2012, he sold the business to a group of investors to put the company on a sustainable path for the future. Five years later, the new owners presided over its liquidation.

Undaunted, Connor, then nearing 70 years old, rebooted the business with pretty much the same business model. He even went the investor route again, bringing on North by East Property, led by local businessman Gregor Kent, to help finance the effort.

In February 2019, Connor hired Glenn (Skip) Wyer as COO, a 58-year-old venture capitalist from Minnesota. Within six months, Wyer was promoted to CEO, despite having no experience in home building or construction prefabrication.

Around the same time, Kent’s group paid $1.84 million for the 50,000-square-foot factory in Middlebury that Connor Mill-Built Homes was partially leasing for production, a move Wyer said showed the group’s commitment to the company’s growth and its 22 employees.

But by November of 2019, Wyer had resigned, and North by East Property was about to pull the plug on the company, which it did in February of this year.

What caused the sudden change of heart? In an interview with Pro Builder for this article last summer, then-CEO Wyer said that Connor was looking for partners to codevelop residential communities for the company to supply with homes, expand its network of contractor customers, and deliver components for about 30 homes in 2019—double its 2018 total. He and Connor also were evaluating potential growth avenues, such as single-family rentals and smaller, more energy-efficient homes.

But Connor tells a different story, namely that he wanted to continue with reproduction house kits—an outlook that eventually excluded him from strategic discussions. Neither Wyer nor Kent responded to follow-up inquiries for comment.

On the outs at the company he’d founded 50 years earlier, Connor and his wife launched a home-based consulting business to provide design and component manufacturing for historical reproduction homes.

And, a month before it shuttered Connor Mill-Built Homes, North by East agreed to lease 20,000 square feet of the factory building to builder Silver Maple Construction, of New Haven, Vt., for its high-end, energy-efficient homes and custom kitchen, bath, and renovation work.

Future-Proofing Your Business

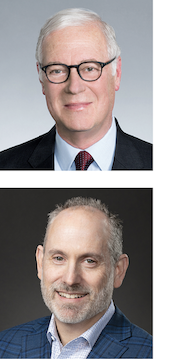

In September, Florida-based Arthur Rutenberg Homes, with a network of 45 franchises operating in 10 states, promoted Jim Rosewater (below, bottom), a 21-year company veteran, from COO to CEO, replacing Frank Pizzica, who remains in an emeritus role.

Simultaneously, the company rebranded itself as AR Homes, with aspirations to double its growth in the next five years through design innovation and customization, full pricing disclosure, and its “proven process” for streamlined luxury-home construction. It also wants to enhance its customer-experience approach through 3D modeling and virtual tours of homes and properties. “We intend to be a leader in every phase of the business,” Rosewater says.

Chairman Barry Rutenberg (at left, top) says the company’s owners have dedicated more resources to realize that game plan. And in recent months, AR Homes has shaken up its executive suite with several personnel changes, appointing Don Whetro as EVP of franchise operations and elevating Kelley Vitorino to lead all of the company’s interior design work. It’s also looking for a new chief technology officer and a new chief marketing officer.

Rosewater believes the timing of AR’s corporate maneuvering is auspicious. “We live in a world where change is happening at an incredible rate,” he says. “Independent builders are looking for solutions to everyday problems to stay competitive and they want partners that can develop software, products, and vendor relationships,” a role the retooled AR Homes now seems geared to fill.

Access a PDF of this article in Pro Builder's April 2020 digital edition