| Contact Scott Sedam via e-mail at scott@TRUEN.com

|

I love nature shows. After a long day traveling, I can kick back in a hotel room and watch "Animal Planet," "National Geographic Traveler" or "Nova" and be quite content. I’d be happy to watch any Jacques Cousteau special for the third time. I especially love it when something from nature serves as an apt metaphor for a business phenomenon. There’s something strangely reassuring about that. While reading USA Today on a plane this week, I ran into one of these metaphors in an article about fire ants.

I have a particular interest in fire ants, having once lain down on a nest of these horrific little beasts in South Florida. After a pleasant jog around a small lake at a hotel, I decided to take a brief catnap on a nice-looking patch of Bermuda grass by the water. Big mistake. Really BIG mistake. I woke up from a horrible dream that I was being attacked by ants — to a reality that was even worse. My entire right side ended up looking like it had been nailed with a 12-gauge at close range. For the next week, I was the "Benadryl Kid" -- nearly addicted to antihistamines. Ever since then, I’ve been hoping to get even.

In the fire ant article, Sanford Porter of the U.S. Department of Agriculture described the introduction of a natural parasite, the phorid fly, into southern states to do battle with the ferocious fire ant, one of earth’s most prodigious and effective creatures. His description of the phorid was fascinating:

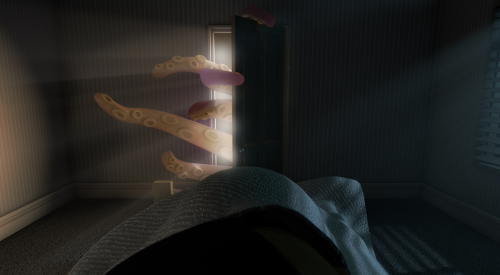

"In action, the phorid hovers over the fire ant like a tiny helicopter, darting in at a tenth of a second, injecting a torpedo-shaped egg into the ant’s body, before buzzing off to attack the next ant in the fly’s brief life span. Once injected, the egg hatches and the larva travels through the ant’s neck and skull, where it eats the brain. Meanwhile, the larva releases an enzyme that dissolves the ant’s joints, making the head fall off. Fastidious worker ants then carry off the infected head to an ant garbage dump located outside the mound."

Wow. That’s creepy, but it serves the little bastards right, I thought. But after reading on and thinking it over, I started to feel a bit sorry for the fire ants. They were hard-working little critters, just doing their jobs. What’s more, there was something strangely, almost disturbingly, familiar about the phorid behavior.

A few moments later, in the business section of the same paper, I read about the continued fiasco at AT&T, now trying to rally its disgruntled workers for a third major reorganization and an umpteenth change in business strategy. The interviews vividly reflected the contrast in opinions and attitudes between the presumptuous corporate types and the erstwhile field force, who felt misused and abused as they prepared to be dumped upon the corporate scrap heap (outside the mound). And it hit me. I turned back to the article on the phorids and read again the above quote. And I said "Wow" for the second time. The feelings of the field guys about the corporate guys were described perfectly by the parasitic phorid’s strange behavior.

In the 26 years since I graduated from college, I have spent about half of them as a field guy, half as a corporate guy. They are very different worlds, and I have concluded that I was very fortunate to have begun my career in a field operations position. Even better, I did it in a very large company (U.S. Steel) with a particularly bureaucratic, even oppressive, centralized corporate structure. Yes, we field guys loathed the corporate guys -- with a passion. Yet, this gave me a basic sensibility that I have tried never to abandon. Call it a "field bias."

When you are out there every day on the firing line with the customers and the people doing the work, you just naturally look at the world through different eyes. So many corporate types simply never understand this. It’s a paradigm problem of the highest order. They just can’t see it. It is not that the field perspective is better per se than corporate’s. Each group sees things the other cannot. Each group has an important role. And I have many times seen a field group so lost in the trees that they cannot see the forest. But generally speaking, I find that the field view comes closer to the essential truth of how an organization functions and is more reliable when trying to determine what the key issues are.

You’ve all heard the old joke, "I’m from corporate -- I’m here to help." Corporate folks would be wise to consider why this always gets a reaction from the field people. The field has simply lived it too many times. The corporate helicopters dart in, lay their eggs, the joints fall off, and the brains get eaten. The carcasses of the ferocious little fire ants are found in the dump, destroyed from within by an agent from without. Sure, the flies often don’t live long, but they leave a lasting legacy. This gives new insight to the popular term "brain damage" in business. Now you know where it comes from.

If you are a corporate employee and I’m starting to aggravate you -- good! Because I want you to think about your role and the impact you have on the field. The desire to control things centrally is certainly understandable and at times even justifiable. But trying to control a dynamic, close-to-the-ground field operation from a spreadsheet-gilded tower a thousand miles away hurts more than it helps. A brief study of the old Soviet-style central economy confirms this vividly. At some point, you have to decide whether you are a federalist or a states'-rights advocate. Guess what? There is loss either way -- you’ll never find the perfect system that optimizes a balance between field freedom vs. centralized control. About halfway through my corporate career, this revelation dawned on me as I remembered my field experience at U.S. Steel and Motorola and how corporate actions negatively affected us -- or maybe it was simply beat into my hard head by some tough-love field guys who didn’t want me to fail.

So in matters of government, I have come down on the side of states' rights. There are a few issues, such as civil rights, military forces and health & safety, that rightly require national-level rule and law. But most other issues should be left to the locals, even if they screw up now and then -- and they will. Our companies should be no different.

The old saying "the government that rules least rules best" used to be an empty slogan to me. Having studied organizational behavior now for a quarter-century, I have concluded that it’s true. Corporate staffs that violate this rule never earn the trust of the field people. Without this trust, they never get their full cooperation. The result -- you’ve all seen it -- is an organization that is less than the sum of its parts.

My advice to corporate is to abandon your helicopters and enter the fire ants’ territory on the ground -- at their level. Don’t try to get inside their brains, don’t lay any parasitic eggs, don’t weaken their structure or go chopping off heads. And yeah, clean up after yourself before you leave. If you make a habit of working this way, maybe they’ll begin to trust you. Maybe then they’ll let you help.

Also See:

Scott Sedam's Editorial Archives