President and CEO of Telemark, Inc, a Hamptons-based luxury home building company, Frank Dalene says that it's part of his Norwegian culture to be a good steward to the environment, so after the oil embargo in the mid-70s, he focused on creating houses that were more energy efficient by tracing carbon emissions back to their source.

Today, his patented carbon calculator, otherwise known as the ICEMAN methodology, helps homeowners and builders make conscientious decisions about the products and materials used in new and existing construction projects by tracking the lifecycle of emissions from material production to at-home application. With policies like the Inflation Reduction Act poised to make waves in a burgeoning green building industry, his carbon lifecycle analysis is perhaps more impactful than ever before.

How exactly do you measure emissions through the ICEMAN methodology?

About 78% of carbon emissions worldwide come from the burning of fossil fuels. So really, it has to do with measuring the amount of energy required to manufacture, distribute, and implement products. For example, concrete has one of the highest carbon footprints of all building materials, second to aluminum, and the process of creating concrete requires high heat and releases a substantial amount of carbon.

Sometimes the majority of damage done happens during the process of manufacturing, but most of the time, it's the energy that's being used. Every time that a human hand touches something, whether it's through transportation or through application, we can track and measure the output of fossil fuels. We follow the greenhouse gas protocol that's put out by the World Resources Institute, which is a worldwide standard for this type of measurement, and there are three scopes of measurement.

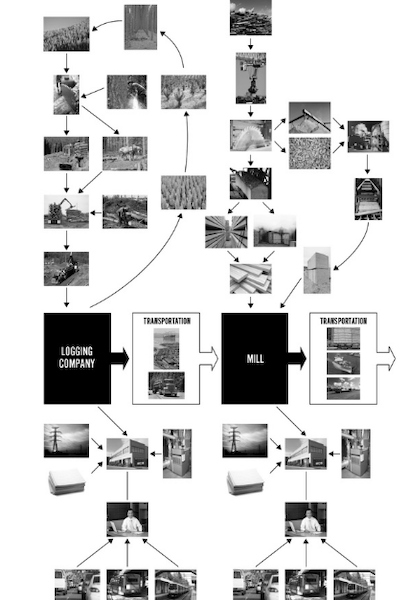

Scope one of the analysis measures direct emissions from the source, so, for example, extracting natural gas for heating. Scope two is offsite production, and scope three includes the actual use of the products as well as other odds and ends of emissions like transportation. I do what's called a lifecycle analysis, which tracks all the energy it took to make that material up to the point where it leaves the manufacturer.

How did the ICEMAN methodology come about and how is it used by homeowners today?

About 10 years ago, I founded the Hamptons Green Alliance, which is a not-for-profit organization building and related-service professionals who collaborate together to build groundbreaking, innovative homes. At that time, we completed a home in Water Mill, which was the largest LEED Platinum home in the country. It was the first home where the carbon footprint of the construction stage was measured. I invented the methodology for that measurement by applying science from the greenhouse gas protocol, which supplies the world's most widely used greenhouse gas accounting standards. We had it third party certified and certified carbon neutral, so that was really a groundbreaking project. I was invited to submit a paper to the American Institute of Physics’ Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy about the building of the Water Mill house that was peer reviewed and published in 2012.

Since then, I’ve developed the ICEMAN methodology to include all manufactured products and mathematically convert the information into an indexing system from one to 100 that the consumer can understand very easily. The system outlines the carbon footprint of building products, going all the way down the supply chain to when each natural resource involved in its production came out of the ground.

The Senate recently approved the Inflation Reduction Act, which could have a substantial impact on the future of green home construction. If passed, where will that funding be allocated in the construction industry?

The Inflation Reduction Act will allocate a lot of money to the residential construction sector to increase tax benefits for renewable energy. That might be for putting solar panels on a house or investing in other kinds of energy saving equipment. There used to be lifetime caps for certain tax benefits, but now, they're looking at it on an annualized basis. For example, a homeowner can spend $1,200 a year to budget things in more of a sequential way. One year, a homeowner may focus on windows, and the next, they might be replacing their appliances. Year after year, that $1,200 annual tax benefit is going to help a lot.

It was initially the incentives that actually got everything moving toward energy efficient construction in the first place. Now, it makes total financial sense. Specific incentives are making it both more environmentally logical and more financially feasible for builders and remodelers to make better choices about what they’re putting into their home projects. It's the older homes that actually need the most work, and these incentives will boost energy savings with little sacrifice from builders or homeowners. There is instead much to be gained when making these smarter decisions.

READ MORE: NEW PRODUCTS

Where does green construction fit into the conversation about affordable housing and how can builders incorporate new products and make effective retrofits while still making sure that each project is catered to every price point?

The bill also includes a provision for green banks that deploy low-cost capital for solar energy projects. They can lend money to homeowners to help them fund these green projects. For example, if a homeowner is putting solar panels on their house and the payback period is seven years, they can take out a loan for 10 years, which would be easier to pay back. There's really no additional money coming out of pocket, so that's what makes it affordable. Over time, the energy savings are actually paying that loan back for the initial cost. That really opens these projects up to a lot more homeowners in terms of affordability.

I think we need to focus more on making affordable housing energy efficient because those are the homeowners who can least afford those increasing energy costs. When you do this, you're giving them financial benefit, but you're also helping the environment.

Will this new legislation have a direct impact on building codes and standards? Do you think that more progressive, sweeping changes could follow as a result?

There are a lot of emerging technologies out there and we see them coming up really fast. As a builder, it can be kind of a scary thing because what it doesn't have is a test of time. And from a contractor or builder standpoint, that can be a liability issue. But if they work well over time, these new innovations can set a precedent.

I'm a chairman of the Energy Sustainability Committee in the Hamptons on Long Island, and we recently built an offshore wind farm, which ultimately led the town to set a goal to be 100% renewable. We were the first town on the east coast to make such a commitment. After we set that goal, the town of Southampton also made a commitment to be 100% renewable electricity. Then the governor and his family came out to the Hamptons to vacation, saw what we were doing, and made a goal for the state to be 100% renewable by 2050.

There are now 30 gigawatts of offshore wind coming off the East Coast from Massachusetts, all the way down to South Carolina. In the next five to 10 years, the entire East Coast will have a lot of this renewable energy in their infrastructure. Once the funding and the planning is in place, the standards inevitably change.

This new legislation aims to reduce over 200 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions by 2030, which sounds like a lot to the average person. What would you say to those who question whether that goal is attainable?

A lot of people certainly struggle to understand the scope of it, and that’s why I developed ICEMAN. I turned it into an indexing system because the measurement for carbon emissions is in metric tons, but we're on the English system, not the metric system. We understand how much 20 pounds of propane is when looking at a tank of it. We can visualize that, but what's a metric ton? How much is that? What does that look like? It does sound like a lot, but there's a lot that can be done to reduce emissions from older homes.

As new technology is developed to reduce each person’s carbon footprint, it'll start making more and more sense where those emissions were previously coming from, whether it be from cars or homes because this change happens over a period of time. Personally, my goal is for my house to be completely free of fossil fuels. I'm now producing 40% more electricity than I'm consuming, and I also have to add room to get an electric vehicle. On top of that, I have a battery backup that has an automatic transfer switch built into it. When the grid goes down, the battery kicks on to power my house. Between my solar panels and the battery, I can continue to live off the grid.

These are the kinds of possibilities we have, and we’re still studying them to make them even more efficient for future generations. I believe our future is really bright. We have a lot of new technology on the horizon that will make these goals not just attainable, but a reality.

Your new book Decarbonize the World outlines the role of the world’s largest carbon emitters and proposes solutions for reducing their footprint. Where in that conversation does the residential building sector come into play and what do you think it will take to bring about these changes in an industry that has traditionally regarded change with hesitation?

The construction industry faces change with hesitation for good reason. These kinds of ideas take time. This is not something that happens overnight. It's a natural transition. I don't believe we'll ever get away from some harmful practices, but increasingly, we’re finding ways to apply old materials and techniques in a more efficient, eco-friendly way, so we're getting there, and there are a lot of moving parts right now.

Over time we’ll begin to adopt new technologies and there will emerge a clear winner, depending on financial benefit and how well they work over time. The goal is for energy efficient technology to come out on top by performing well beyond the tried and true to become the sensible replacement.

Our behavior needs to change as well as we dive deeper into these green technologies. I believe we're creatures of habit, and over time, we’ll get accustomed to it and we’ll like it because of what it does. When it saves us money while simultaneously saving the environment, how can we say no?