| Contact Scott Sedam via e-mail at scott@truen.com

|

Many years ago, before I limited my work to the home building industry, I worked on a project for a hospital in the near-suburbs of a big Midwestern city. An older hospital, it was in the midst of a major transition, having just completed extensive remodeling to bring it up to speed with competing facilities.

Hospitals are characteristically very political organizations, with strictly defined positions and an extensive hierarchy. Often, there are continual wars -- admitting vs. surgery, dietary vs. x-ray, pharmacology vs. rehab and doctors vs., well, just about everybody. It's not unusual for the patient and family members to feel neglected, an afterthought. Many of you know exactly what I mean.

That was the case at Heartland Hospital. Murray, a promising young CEO, was hired to direct the "cultural change." He quickly hired an outside consulting firm (the one I worked for) to help him implement new operating procedures. Together we learned some very important lessons.

Management Misstep

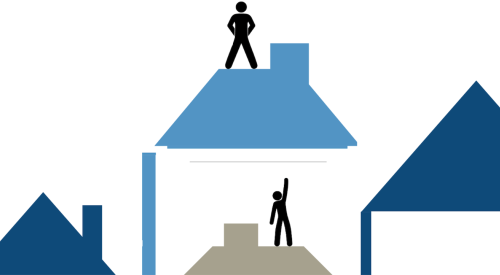

I recall, in particular, two incidents that reflect the classic leadership dilemma many of you face every day: when to step in and assert yourself and when to lay back and let the people go on their own.

In the first incident, our "patient satisfaction" survey indicated a handoff problem between the 3 to 11 shift and the 11 to 7 shift, resulting in a lot of disgruntled patients. So Murray and I, being hands-on/results-oriented MBA types, seized this problem and decided to get the nurses together to solve it. We picked a unit, 3 West, and told the 3-11 staff to stay a half hour late and told the 11-7 group to be in a half hour early. We would bring in a couple of floaters to help cover things on the unit while we had our problem-solving meeting.

Quite proud of ourselves, we showed up for our 10:30p.m. problem-solving meeting expecting quick success.

The meeting started on a sour note and went downhill from there. We heard it all. Was management going to pay for this overtime? Why was 3 West singled out? And it was insulting to think a couple of floaters could cover for them... On and on it went. We accomplished nothing. Back to the drawing board.

A New Approach

About two weeks later, we decided to try again. We picked the 2 East unit, but tried a different approach. With my coaching, Murray first showed up on the 3-11 shift, pulled the staff together for 5 minutes, laid out the problem and said:

"I don't know how to solve this, but I don't think we can do it without getting together with the 11-7 shift and working it out. I don't know how to do that, but if you all can come up with a plan, let us know. We'd be happy to get you a room, pay overtime, bring in floaters, whatever. Let me know if you think of something."

The next morning he came in extra early and gave the same speech to the 11-7 shift. About two days later, the head nurse from 2 East stopped in Murray's office with the plan. She said that people from each shift had talked it over and decided that if the 11-7 shift came in a half-hour early and the 3-11 shift stayed a half-hour late, they could meet together! And, if it was no more than once a week, no floaters would be necessary -- they could work it out between themselves. They also agreed no one would file for overtime because they were so happy that they were finally getting a chance to work on these problems with management's support!

We were stunned. It was just what we had tried to do with 3 West -- with a critical difference. Ownership. They bought into the problem, accepted it as their own and thus were more than willing to make the sacrifices necessary to solve it. We trusted them to do the right thing and they did. A good lesson for all of us.

Taking the Lead

My story would be neat and tidy if we could just stop there, saying, "A-ha! I have it! The secret of leadership is ownership and empowerment." But just three weeks later, another lesson came around. Murray had been doing talks on the importance of communicating not just with patients, but also with families and visitors. He felt that everyone was paying him lip service -- nothing seemed to change. Staff members always appeared too busy to really help someone who was lost in the hospital labyrinth. Murray was really frustrated, so I gave him the standard consultants' "it takes time" speech. He didn't like it much.

When I returned a few days later, Heartland had changed. Staff members, even the most grizzled docs who normally ate scalpels for breakfast, were starting to talk to each other. Employees were stopping to help patients or visitors. Staff members were laughing and pointing to each other with knowing grins. What they were pointing at was a button that literally everybody had on. It said, quite simply, in small print, "Proud Associate of Heartland Hospital." In larger print, it proclaimed, "Ask Me. I care!"

I walked into Murray's office and he leapt out of his chair, grabbed two boxes and thrust them at me. He said, "Here! As long as you're on this project you need one of these too." He explained how he had spent the previous two days telling each employee face-to-face that they had to wear one of two buttons he had made up. Their choice. In a mostly empty box were the "Ask Me, I care!" buttons. In the other, nearly full box, was an almost identical button, saying "Unhappy Associate of Heartland Hospital. Don't Ask Me. I don't care!"

I was stunned, and asked Murray if he had, indeed, lost his mind. It was the most blatant act of management trying to force change down everyone's throat I had ever witnessed. It absolutely, positively, would never work! But it did.

With the advent of Murray's buttons, Heartland underwent a dramatic transformation. It was as if everyone suddenly had permission to be nice, to listen, to care. I think they had always wanted to, but the norm had been to always be too busy to stop and help. This culminated in Heartland Hospital being featured in a major ad for IBM during a Super Bowl. You can imagine the excitement. Murray's buttons were visible on every employee in the ad -- even on the emergency room doctors.

Which Is Right?

As is my nature, I've really mucked things up. What's the answer? Hands on or hands off? Go in and shake things up or sit back and let them figure it out?

In the final analysis, there is only one conclusion we can make. It's not very satisfying to simply say, "it's situational" -- but it is. Leadership is tricky stuff. We have come a long way in the areas of participation and empowerment and we are mostly better for it. But at times, what passes for hands-off, looks more like uninvolved and not caring. At other times hands-on is just plain old dictatorial control. The skill is determining what type of leadership is called for -- and making the right call. That's not easy, but that's the job of a true leader.

There now. Go make some buttons -- but maybe ask your people what they should say.