A builder's ability to control land without owning it, Ben Anderson, Len Forkas and other builder-developers say, puts his or her company on a higher, more profitable plane than those who rely on others for finished lots. This ability typically lies in the richness of a given builder's local development experience as well as his or her ties to social and political structures in specific communities. These ties translate to:

A lack of local connections does not preclude builders from controlling and developing out-of-town sites. Builders such as Wayne Colmer often succeed even when they come from another part of their state. These builders often hinge their business plans on succeeding with tough but profitable opportunities anywhere they can be found. In exchange for diligent work to secure a higher use (and a more profitable yield for their property), landowners gladly will enter a contingent purchase agreement with such a builder.

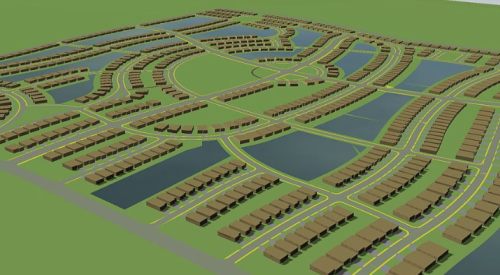

"My company's strategy is to develop land in areas where there is an imbalance between supply and demand and where we can compete with production home builders because they want to avoid getting involved in uncertain entitlement processes," Colmer says.

Six-and-a-half years in the making, Colmer's latest new home community, in Morro Bay, Calif., near San Luis Obispo, sits atop a bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Today, with permits in hand, Colmer stands to profit handsomely for the breathtaking but calculated risk he assumed entitling this environmentally sensitive land for a grateful landowner. Chances are, had Colmer not offered to take charge of the parcel, the landowner would have netted far less for it. And therein, Colmer and others say, lies the key to controlling land without owning it.

With diligence, luck and tenacity, builders with a track record for winning entitlements and a stomach for riskier deals offer a compelling, more lucrative solution to vast numbers of landowners.

Tom Bruin, a Chicago-based principal with residential land investor Hearthstone, says a builder's potential profit grows by an average of 20% when building on lots he or she develops from raw land.

The same point is made by several industry studies, including one authored by James Pugash of Hearthstone and Kenneth Rosen of the University of California, Berkeley and published in PB in January 2003. The run-up in home prices in recent years results primarily from the increase in the value of residential lots. The value of the sticks and bricks remains stable. Thus, despite the risk, developing land remains the surest way for builders to realize the highest gain from the strongest housing market in decades.

Several of the industry's largest firms feed their home building operations by "locking up" finished lots with option agreements secured by nonrefundable fees or deposits. The prices of these option agreements vary from market to market. So, too, does the ability to buy options on finished lots.

Las Vegas builder Tom McCormick reports that builders in southern Nevada take down large "super pads" from big master-planned communities - final maps and permits not included. The new home market there, he says, is too hot for options to work.

Keith Christopherson of Chistopherson Homes in Santa Rosa, Calif., says land control conditions there resemble those in Las Vegas but are not as extreme. Option deals still get done, but less frequently. Big pieces in excellent locations, even those needing everything from annexation agreements to time-consuming environmental impact reports, still sell for cash even though homes won't be constructed on the site for years.

Some publicly traded builders consciously decide to not be in the development business because it involves a different set of disciplines. Other publicly traded GIANTS find option agreements the best way to reflect their return on invested capital. These scenarios represent special circumstances suitable for a separate discussion.