Condominium construction is picking up again. The biggest stirrings are in markets like Austin, Texas, which experienced a smaller dip in property values than other metropolitan areas. But it’s safe to say that there is more for-sale multifamily housing in the pipeline now than there was three or four years ago.

“It’s been high-density housing for several years now, and we’re starting to see a resurgence in the for-sale market, both single-family and multifamily,” says architect Keith Labus, principal of KTGY Group, Irvine, Calif. “We’re starting to see more townhomes.”

While this might signal the beginning of a slowdown in the rental apartment market, Labus qualifies his opinion with, “We’ll have to wait and see.”

“There’s still not a lot of financing available for condo projects, but the market is there,” says Adam Nyer, owner and president of Skybeck Construction. “I think those projects are all in the hopper right now and going through entitlements. You’ll probably see them roll out over the next few years.”

Low rents and high occupancy rates continue to support the production of large apartment projects in Austin. The Denizen Condominiums, a project that Nyer is building two miles from downtown Austin, doesn’t have a lot of direct competition. But Nyer and his partner, developer Terry Mitchell, didn’t just get lucky with The Denizen. Location, design, site planning, on-site amenities, sustainability, and value all played a role. The same is true of the two rental communities profiled in this article.

Austin condos lure downtown dwellers

In Austin, owners of downtown high-rise condominiums are moving a couple of miles away to take advantage of more square footage, more open space, and hard-to-find amenities such as dog parks and vegetable gardens.

Credit Terry Mitchell for his tenacity in bringing The Denizen to market. Due to the housing crash and a lengthy entitlement and financing process, it took five years for Mitchell, president of Momark Development, to start construction on a property in South Austin he had purchased from the Salvation Army.

After many meetings with the neighborhood association, the development team — Mitchell, Nyer, and Skybeck’s Bill Skeen — worked with Dave Copenhaver, a partner with BSB Design in Dallas, on a concept that would appeal to the eclectic nature of Austin residents.

The project starts at the top of a hill and slopes downward, providing views of downtown Austin. In addition to 119 condominiums, The Denizen includes a two-acre park, two dog parks, a swimming pool, an outdoor kitchen and dining area, an amphitheater, walking trails, and a half-acre community garden.

Click here to see the Denizen site plan.

Today, the average price of a resale home in that neighborhood is about $380,000. Anything new starts in the upper $400,000s. The Denizen offers a mix of flats and townhomes ranging from 735 to 1,931 square feet and the upper $180,000s to the $400,000s.

To attract a younger, hipper crowd, Copenhaver gave the buildings a modern look expressed by stucco and stone exteriors, flat roofs, and linear window patterns. The light-filled floor plans have a strong visual connection to the outdoors. Thirty-nine units have private, fenced yards. The townhome buildings are duplexes, with a 1,600-square-foot unit on one side and a 1,900-square-foot unit on the other. The flats are spread out across 10 buildings, with 10 or 11 units in each.

A bus stop in front of the development provides transportation to downtown Austin, including the capital district and the University of Texas. There are also bike racks and places for car sharing, though Mitchell acknowledges that residents aren’t ready to give up their cars.

“Our model is not even open and we’ve got 30 sales,” says Mitchell. “That’s music to my ears. People are seeing that a community with this kind of open space located a five-minute drive from downtown, with homes that have twice the square footage, is a great value.”

Nyer says the demographics are all over the board. “We thought it was going to be a lot of SINKs (single income, no kids) and DINKs (double income, no kids), and we’ve gotten some of that. But we’ve also gotten a lot of empty nesters whose children live in Austin.”

Click here to see the second floor layout.

Click here to see the third floor layout.

Click here to see the tuck-under garage.

Tuning in to what buyers want

After developers Terry Mitchell, Adam Nyer, and Bill Skeen, along with Dave Copenhaver of BSB Design, came up with preliminary floor plans for The Denizen, they asked sales manager Catherine Thomas for her input. Thomas, who has sold condominiums in downtown Austin for the last six years, recommended these modifications:• Garages. “The original plan was to just do carports. But as much as people want to be green, they still want their cars. A lot of buyers would not have purchased townhomes if they didn’t have garages.”• Yards. Former high-rise condo dwellers are moving to The Denizen because they’re tired of going in and out of the elevator with their dogs. Also, empty nesters who are buying first-floor units love the yards, which are maintained by a homeowners’ association.• Bedroom separation. “Some buyers are still in the roommate stage, so it was really important that the bedrooms not be on adjacent walls.”• Bicycle storage. In addition to the bike racks outside, there’s a bike storage room in every building.• Usable patios. They aren’t just decorative, says Thomas: “You can actually fit a table and chairs on them.”

Affordable housing for a high-priced city

According to the NAHB, San Luis Obispo County, Calif., is one of the least affordable housing markets in the U.S. “The NAHB ranks SLO County the second least affordable metro area, behind only New York City,” says Jerry Rioux, executive director of the SLO County Housing Trust Fund. The 2010 U.S. Census reported that 35.8 percent of renters in SLO County had a severe housing cost burden.

The demand for affordable rental housing is especially acute in the city of San Luis Obispo, home to California Polytechnic State University. Cal Poly students compete for housing along with the local workforce, Rioux says.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that the Village at Broad Street is 100 percent leased. Built on a former parking lot, the Village offers 42 apartments that are affordable to families with annual incomes ranging from 30 to 60 percent of the area median income. The on-site services include a community room with a kitchen and library; a computer center; a fitness room; and an outdoor playground. There’s also approximately 7,200 square feet of ground-floor retail.

The Village is less than a mile south of downtown San Luis Obispo. Public transportation is a quarter of a mile away.

KTGY designed the buildings to integrate with the surrounding historic railroad district. “We did that partly through the use of materials such as brick,” says architect Keith Labus. “The arches on the mixed-use building came from the old railroad roundhouse concept, and terminate at the rear. That’s what you see when you drive through the entry to the back of the project.”

The developer, ROEM Corp. of San Jose, Calif., financed the project via a combination of low-income housing tax credits, loans from the city and the SLO County Housing Trust Fund, and American Recovery & Reinvestment Act funds.

Click here to see the Village at Broad Street.

“The Village at Broad Street provides high-quality affordable apartments and access to retail services, which are important to this community,” says Jonathan Emami, VP of ROEM. “With our commitment to developing and maintaining public/private partnerships with local governments, providing affordable housing that is indistinguishable from market-rate housing, and utilizing environmentally responsible building techniques, we feel that the Village has set new standards for craftsmanship, community, affordability, and sustainability in San Luis Obispo.”

According to ROEM, comparable market-rate properties in the region have limited vacancies and command rents that are, on average, 20 to 35 percent higher.

Rowhouses fill gaps in Philly rental market

University City is an up-and-coming section of Philadelphia that serves the University of Pennsylvania and Drexel University. “Each year it grows a little bit,” says Charlie Kamps, co-founder of AmeriSus in Penns Park, Pa.

AmeriSus is short for the American Sustainability Initiative, which started in 2008 and delivers a whole-home package to the builder, including design, engineering, schedules, systems integration, materials, products, appliances, and finishes. “The whole concept is to eliminate the waste in labor and materials so that at the end of the day you have a lower-priced home, whether it’s for sale or rental,” Kamps says. “Plus, the utility bill is a fraction of what you would typically experience in a similar size, conventionally built unit.”

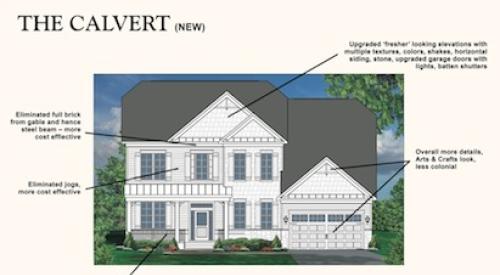

The AmeriSus concept is a no-brainer for neighborhoods like University City, where demand for affordable apartments is high, construction costs are daunting, and new housing has to be shoehorned between older buildings on tight infill sites. Lomax Real Estate Partners of Chalfont, Pa., is building an AmeriSus design called the Philly 16 on scattered sites around the area. The 16-foot-wide, three-story rowhouse has an apartment on each floor that is approximately 950 square feet, with two bedrooms and two baths. Bay windows in the master bedroom of the upper-level units bring in natural light along with windows on a side wall. The apartments are earmarked for local workers and graduate students.

Click here to see to the front view.

The beauty of the design, says Kamps, is that the dimensions can be varied to fit the site. “At the push of a CAD button, we can change a Philly 16 to a Philly 14 or a Philly 18,” he says. “And because there are no interior bearing walls, the plan of an entire floor or an entire building can change according to what the builder wants.”

With the AmeriSus system, a completed building can be delivered in about six weeks, says Kamps. Lomax plans to build a total of 26 rowhouses.

Like all AmeriSus homes, the Philly 16 features SIP exterior walls; triple-pane windows; water-conserving plumbing fixtures; and Energy Star appliances. Each apartment has its own, high-efficiency HVAC system.