| Just two miles from downtown Austin, Penta Development’s The Summit at West Rim proves selling green estate homes to wealthy deer lovers is a viable, and profitable, concept.

|

Residential development has never been easy in Austin. Astride the Balcones Escarpment, with rocky, cedar-covered Texas Hill Country to the west and fertile blackland prairie to the east, this land has been a battleground since the first environmentalists (native Americans who loved the land for what it was) put arrows in the backs of the first developers (settlers who loved it for what it could be). But today, after 300 years of fighting, builders are beginning to find common ground with environmentalists in this sensitive and scenic Texan Shangri-La.

With a major university in town, Austin has always been, like Boulder, Colorado, among America’s toughest communities in which to get a project approved. Large numbers of biologists and zoologists roam the countryside, and many of those sporting "Ph.D." behind their names are not shy about opposing any kind of development. Austin’s builders and developers did not find commonality with environmentalists by opposing them. Capitulation is closer to the truth.

The thaw in relations comes at a time when Austin is booming as never before, and that may be a key element of the détente. A magnet to high-tech wealth creation, Austin now claims more millionaires under the age of 30 (per capita) than any other city in America. With all that new money, Austin can afford to tread lightly on its most pristine, and precious, parcels of undeveloped land. Computer manufacturer Michael Dell, for example, recently paid $84 million in cash for approximately 1800 acres of Hill Country on Lake Austin, with plans to turn it into an equestrian park for his employees.

Developers here are learning to work with environmentalists because, especially on Hill Country parcels, they know the market will bear the costs of just about any measures they must take to gain the support of government and local citizen groups. Going from one-acre to two-acre lots? No problem. When you’ve got a waiting list of home buyers eager to shell out $1 million or more, even the cost of endangered species mitigation is a minor annoyance.

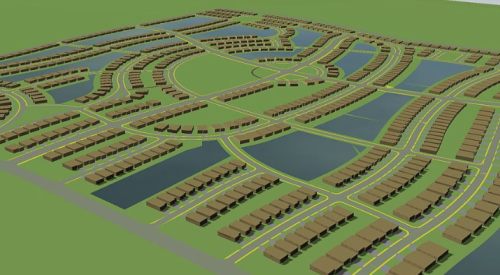

| The Summit’s rocky, tree-covered site peaks at 900 feet above sea level then plunges to 408 feet, just 30 feet above the pool-level of nearby Lake Austin. Using natural drainage, The Summit employs "energy dissipaters" (far right) to slow downhill flows and prevent erosion. Street location was guided in part by efficient paths offered by deer trails (center). |

In fact, Austin’s high-end builders and developers are learning that, in the face of such market dynamics, less often translates into more. On prime Hill Country parcels, reducing the density, treading softly on the land and bending over backward to give nature-lovers everything they ask for often increases their returns. The reason is simple: the buyers are also nature-lovers. And they are willing to pay more to live in ecologically sensitive neighborhoods. In Austin, they are willing to pay a lot more.

"These are really smart people," says Austin custom luxury builder Brian Bailey. "They are environmentalists themselves. They believe in what we’re doing...not only because it’s right, but also because it increases the value of the real estate they are buying. Keeping the hills green protects and enhances the value of their investments. And my product starts in the $1.5 million to $2 million range."

Whether less can also be more in other markets, and at prices below $1 million, is open to question. But we know that most housing trends start in the custom/luxury market and then trickle down to lower price points. Is it possible that greenness, like Old World designs, will be the next trend to migrate into the mainstream?

"Consumers will determine how far it goes," says Bailey. "Our whole industry could do a lot more, but it will take a lot to get builders and developers to change their standard practices. Once green building becomes the norm, the costs associated with it will come down. If it does happen, customers will drive it, just as our high-end buyers do in Austin. They demand it. We will not fight our customers."

"Summit at West Rim" Sets Benchmark

With that in mind, the project where Bailey now builds may be setting the benchmark for greening a hot housing market. Penta Development’s The Summit at West Rim is a 150-acre gated enclave of 73 new homes, only two miles from downtown Austin, on a steep and rocky hill overlooking Lake Austin and the downtown skyline. Despite being so close in, this beautiful piece of the Hill Country, near the woodsy but exclusive bedroom community of Westlake Hills, was passed over for years, first because its steep and rocky nature defied servicing, later because governments, planners, neighbors and environmental activists wrangled with owners over whether it should ever be developed.

The site is actually outside the Austin city limits in Travis County. Today, that’s a major advantage.

"We don’t have to process plans through the city," says builder Don Reynolds. "We’re saving our buyers $5000 to $6000 a year in taxes, even though we have city water, sewer and gas service. This parcel was never annexed. It’s a little enclave of county jurisdiction, but it’s in the Eanes School District, which is regarded as the best in this whole metropolitan area. And all of this is only two miles from downtown. So there’s enormous underlying value in this site."

Previous owner Frances Larson Ledbetter began a quest to develop in the early 1980s. Her plan then called for 190 condos on the plateau at the top of the hill, with most of the hillside left undeveloped. Water pressure problems and sewer limitations doomed that one. Later, a plan for a subdivision, at a density of one unit per acre, fell victim to the late 1980s Texas economic meltdown, an assortment of environmental issues and lawsuits, and finally, to the death of Frances Ledbetter.

Penta Development principal Les Canter, now 39, began working on acquisition of the site in 1993, and finally closed on it in 1995. He brought in Austin-based planners Richardson Verdoorn, specifically director of development consultation Sandra B. Nash, ASLA, to deal with the environmental issues, beginning in 1994. If that seems a long time ago, you are beginning to understand what it’s like to develop land in Austin, especially in the Hill Country.

"All the lines were erased from the map, and much time was spent on the property, learning about its character," says Canter. "A new, more sensible and sensitive design began to emerge."

"This is an interesting town," Nash says in describing her approach. "The environmentalists are like watchdogs. The plan that got them really riled up was the proposal to build single-family homes in a traditional subdivision. This is a tough site to carve up into cul-de-sacs because of the extreme topography.

"That plan was brutal in the way it treated the land. We felt that some of the proposed roads could not be built. It also called for septic systems, even though the site is within 500 feet of Lake Austin, which is the source of drinking water for the whole city. That made a lot of people nervous."

Nash and her planners began making early morning and late evening visits to the site. "We sat down, stayed quiet, and listened to what the land had to say," she says. They also watched abundant numbers of white-tailed deer, which are a pest to area residents who fence off their gardens to keep them from being eaten.

"We watched the deer and mapped their trails," says Nash. "The deer trails showed us where the roads should go, which is completely different from where the past plans put them. The deer follow the easiest route to the top of the hill. By following their lead, we were able to minimize the cut-and-fill process and develop a street system that looks very strange when you see it on paper. But when you walk the site, you see the perfect logic of the way those roads work."

In consultation with the Richardson Verdoorn planners, Canter also decided the deer are an asset, not a liability. Community covenants, conditions and restrictions now prohibit fencing that would restrict the deer. "Everybody moving in knows that," says Nash. "We have no plans to control the deer population. They will come and go as they please and walk on people’s yards. If the owners choose to plant pansies, they may get eaten. That’s why we encourage xeriscaping, and many of the buyers are going that way. Those native plants will be far more drought and deer resistant."

Rather than maximize the number of lots allowed on the site, the developer opted for quality over quantity. Fewer lots mean less loss of trees, and the cedars and oaks on the site are the natural habitat for the two endangered species of migratory songbirds identified in earlier studies of the site: the golden-cheeked warbler and black-capped vireo.

| Builders must carefully avoid damaging tagged trees, which include any (other than cedars) that exceed four inches in diameter.

|

Builders at The Summit at West Rim are now required to carefully avoid tagged trees. "We initially tagged every tree eight inches or more in diameter," says Nash. "We also found and tagged some rare species of trees, like the Texas Mountain Laurel. The tree requirements now call for no removal of anything, other than cedars, more than four inches in diameter. And we’re keeping the big cedars wherever possible."

A 20-acre private park, centrally located in the development, is also intended to provide habitat for native wildlife and passive recreation for residents. "The community association could build trails," says Nash, "but I doubt it will happen. We’ve left it completely natural, and we expect it to be used for bird watching and other passive recreational activities."

No endangered birds have been observed on the site recently. The Summit is so close to downtown Austin that it is no longer a fly-over for them. However, development in the area is still subject to approval by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service under the Endangered Species Act. The City of Austin and Travis County also hold what is known as "Regional 10A" permitting power, which allows them to negotiate deals with developers relating to endangered species habitats. In this case, Penta was allowed to build out some of the habitat in exchange for purchasing a 466-acre mitigation tract elsewhere in the Lake Austin watershed. Canter then dedicated this parcel as a habitat preserve as part of the Balcones Canyonland Conservation Plan (BCCP). That’s a joint city/county initiative to protect large tracts of land as habitats for endangered songbirds.

Reducing the density of the project to two-acre lots also allowed Penta to site every lot for city skyline views from the rear of the homes. "People want their view to be from the back of the house, where they can enjoy it," says Nash. "To make that happen, the main road is single-loaded (houses on only one side), which in most cases would be viewed as inefficient. But here, it actually increases the value of every lot, and creates an ambiance that enhances the entire parcel."

In virtually every aspect of the planning process, from laying out the street system to designing mail boxes, signage, bridges and entry features, the key goal is to impose as little on the site as possible.

To develop it, Penta had to agree to make regional improvements to both water and waste-water systems in the area, so the Summit could get off septic and onto centralized systems. "Previously, the surrounding neighbors had pressure problems at their second-story levels," says Nash. "Now they don’t, thanks to the regional improvements Les paid for."

That added to costs, but brought a political windfall. It gave neighbors a tangible benefit, a reason to be for the development instead of against it.

There are no curbs, gutters, or storm-water sewers in The Summit’s narrow, 28-foot-wide roads. "Storm-water drainage is entirely natural," says Nash. "We use gentle, grass-lined swales. As the water runs over the swale, a lot of pollutants drop out. At the road edge, we use what’s called a ‘ribbon curb.’ It’s really just a strip of concrete on each side of the road."

Where the hill is steep and water flows rapidly down it, Penta uses "energy dissipaters" to slow the flow, reducing erosion. These are nothing more than pillars of concrete, at varying heights, built into the swale. "They’re now covered with vegetation, so they don’t stand out," says Nash. "It’s all part of the trade-off from curbs and gutters. But we’ve actually reduced costs dramatically by using these methods."

The Summit caught another break on storm-water retention: it’s not required. "The low point of our project is just 30 feet above the pool level of Lake Austin," says Nash. "With the top of our site 408 feet above the lake, the studies showed that it’s actually better for our runoff to flow into the lake as quickly as possible, so it doesn’t go in at the same time as runoff from other areas nearby that do have retention."

Canter believes The Summit’s minimal impact on the land was a major factor in the fast sellout of virtually the entire project, as builders chosen for the development scooped up every lot in a drawing.

Canter contracted with Brian Bailey to organize the builder groups for both Phase I (42 lots) and Monticello, the second phase (28 lots). Phase III is just four acres, now being planned for four home sites. "I picked six builders who could work together well," says Bailey. "The architecture of their homes had to be complementary. They had to have solid reputations and the financial ability to take part in a project at this $1 million and up price level."

Bailey also had a hand in development of the architectural controls and deed restrictions, which include a requirement for 100% masonry exteriors.

Lots near the top of the hill are larger. On one, Bailey is building a 26,000 square foot house. "I have five houses under construction now that are over 15,000 square feet," he says. "This market is unbelievable. I have six more starts scheduled this year, and we are sold out for next year. I only have three slots open in 2002."

In the case of The Summit at West Rim, the greenness is mostly on the development side, where controls protect trees and rock outcroppings and restrict landscaping and hardscaping. Most of the houses will have stone exteriors; many will be finished in white, Hill Country limestone, a native building material. But just as many owners are choosing non-native stone finishes, to get different colors and architectural looks in keeping with the Old World styles now in vogue. There’s no requirement to use recycled materials or any of the other green building construction methods.

However, the extreme topography and requirements to save trees and rock outcroppings impose plenty of restrictions. "We’re limited to operating within the footprint of the house and boundaries of the surrounding landscaped areas, which are not large," says Bailey. "In doing that, we have to stage our work, so we get a lumber drop for only three days worth of work. Then we get another drop, because we just can’t store much on-site.

"It takes a lot more intensive planning. We have one house at the top of The Summit where we actually brought in two all-terrain fork-lifts, so we can move materials around in these very tight areas."

Many of the houses near the top of The Summit are so large that they step down the hillside. To make that work, they employ "upside down" designs, with living areas at the top (to grab the best views) and secondary spaces stepping down the hill. That can create some interesting staging challenges.

"We had one house where, prior to completing the foundation and starting framing, we had to stockpile drywall in the basement a year in advance," says Bailey. "We knew there would be no way to get drywall down there at any other time during construction."

For all the problems, though, there are huge benefits to involvement in green projects such as The Summit. The builders who were invited and put up the ante to get into the lot drawing had to buy expensive lots all at once. But they are reaping the benefits now.

"The prices we paid for the lots sure look good in retrospect," says builder Don Reynolds. "Most of them were $140,000 to $180,000, some as high as $225,000. We held one lot back and didn’t sell it right away because we saw what was happening. We’ll get at least $425,000 for it. We’re talking about putting a spec house on it."

The first house Reynolds built at The Summit was 5500 square feet and sold for $1.4 million. The second house, under construction now, is 8000 square feet and will bring about $2.2 million. The spec house he is planning will be 7000 square feet. "Whoever buys it will probably pay about $2.8 million," he says.

Reynolds says his hard costs in the development average $200 a square foot, and that the extreme conditions imposed by the development probably account for an extra $5 a square foot. "But that’s mostly the result of the topo, not the greenness of the project."

Unquestionably, The Summit t West Rim is an extreme example of a green building success in a red-hot housing market. One local publication in Austin recently estimated that the city now has 60,000 millionaires. (All of them seem to be in the housing market.) Still, we have to wonder if the potential for more modest successes is not there, waiting to be tapped, in many cities across the country.

It won’t take a $1 million price tag to support it in most places. And there might be a mother lode of high-end, ecologically-sensitive home buyers in many markets, just waiting for the opportunity to go green...and brag about it to their friends.

I’d certainly take a close look at the possibilities in every hot housing market with a big university. Do you read me in Boulder and Raleigh?

| Narrow roads serving the Summit’s three phases follow a pattern set by deer trails on the steep hillside. Signage, bridges and entry features have a common goal: to impose as little as possible.

|