In November 2018, the Camp Fire in north-central California destroyed 18,805 homes in the town of Paradise, essentially wiping it off the map. That conflagration occurred just 11 months after the Tubbs Fire burned some 5,500 homes in Sonoma County, just north of San Francisco, including more than 3,000 in Santa Rosa alone. Less than a year after Camp, the Saddleridge and Tick fires were ripping through Los Angeles County, burning tens of thousands of acres and forcing mass evacuations of homeowners.

Last September, Tropical Storm Imelda dropped an estimated 40 inches of rain on Houston and Harris County, Texas, flooding 1,200 homes and causing $8 billion in damage. Some of those afflicted were still drying out from 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, which dumped a record 50-plus inches of rain on some areas and caused $125 billion in damage to an estimated 135,000 homes.

During 2018 alone, 14 natural disasters across the U.S. caused at least $1 billion in property damage, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The frequency and severity of earthquakes, tropical storms, hurricanes, tornadoes, and wildfires, along with the heightened threat of coastal flooding from rising sea levels caused by climate change, would seem to make resilience an imperative in any new construction or rebuild scenario.

It’s also a good investment. A 2018 report sponsored by The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) asserts that every $1 spent on resilience saves $11 down the road in reducing the need for rebuilding or restoring damaged property.

And despite recent research that found scant state and local incentives to offset the extra costs of resilient construction practices beyond the building code, the federal government stepped in with the Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018, which, in part, mandates resilience and mitigation efforts when rebuilding homes damaged or destroyed by a natural disaster.

An Economic Tug-of-War

The economics of resilience is topical, as natural disasters have become more common and devastating. While the general consensus among homeowners, builders, and city planners is that structures need better protection, there are limits to what homeowners will pay, what municipalities will mandate, and what insurers will cover ... and therefore what builders will do to deliver homes to resist the most intense forces of nature.

While some builders, custom and production, are committed to so-called “enhanced” resilient construction practices that go beyond current building codes, the majority seem content to build only to those requirements for their jurisdictions. And for good reason: They don’t currently build in risky areas (though that map is shrinking) and their buyers, to date, haven’t shown enough interest or willingness to invest much, if anything, for those extra measures.

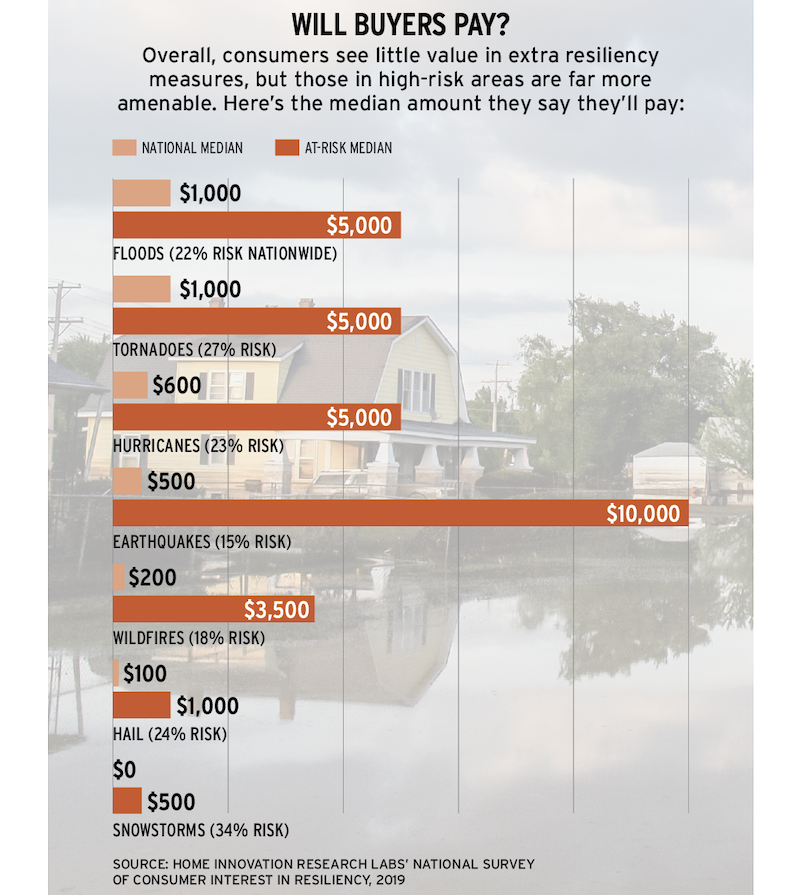

In fact, 60% of consumers believe new homes built to modern standards are resistant enough to natural disasters as-is (and certainly more so than homes built in prior decades), according to a recent survey of nearly 800 consumers nationwide conducted by Home Innovation Research Labs for the National Association of Home Builders. Those in disaster-prone areas are more willing (see Will Buyers Pay? below), but that’s what they say on a survey, perhaps less so in the sales office.

“Consumers think that if a 100-year storm hits someplace, then it’s safe for the next 99 years,” says Alex Wilson, president of the Resilient Design Institute, in Brattleboro, Vt. “Demand hasn’t been there yet for home builders to build in a resilient fashion.” As a result, typically only those mandated by state law or local ordinances to go the extra mile do so, according to a parallel survey of 400-plus home builders by Home Innovation.

With that, nearly one-third to more than one-half of builders—depending on which part of the country they’re in—are unlikely to embrace enhanced construction methods voluntarily, and 40% of them face no formal requirements for enhanced resiliency practices.

Resiliency Low-Hanging Fruit

No doubt, some resilience measures, such as raising a home’s foundation above the floodplain, are pricey. Recent ordinances passed in Houston and Louisiana raise the minimum height of new homes by 2 feet and 1 ½ feet above the floodplain, respectively.

To make that mark using fill material, says Robert Carroll, owner of Carroll Construction, in Clinton, La., costs about $8,000 per foot of height. If a home needs to be raised 3 or more feet to meet the new standard, he fears construction costs could be prohibitive, as it also would require a more complex foundation to mitigate moisture issues under the house.

“Resilience is a good concept, and we should never stop trying to build better homes,” Carroll says, “but you also have to consider the implications of making homes too expensive for people to afford.”

But there are simpler, less-expensive ways to make homes more resistant to extreme weather events, says Anne Cope, chief engineer with the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS), whose Fortified Home program offers several recommendations.

First and foremost, Cope says, is keeping the roof on the house during storms to protect the interior from severe or catastrophic damage. Best practices include using ring-shank nails to fasten roof sheathing and taping those joints, using drip edges to protect the underlayment, and fastening metal straps to secure the roof to the rest of the structure. Applying these measures to a 2,000-square-foot roof would cost less than $2,200, the Fortified Home website says.

That’s more in line with what owners might pay for protection, especially in areas prone to high-wind and rain events (see Will Buyers Pay? above).

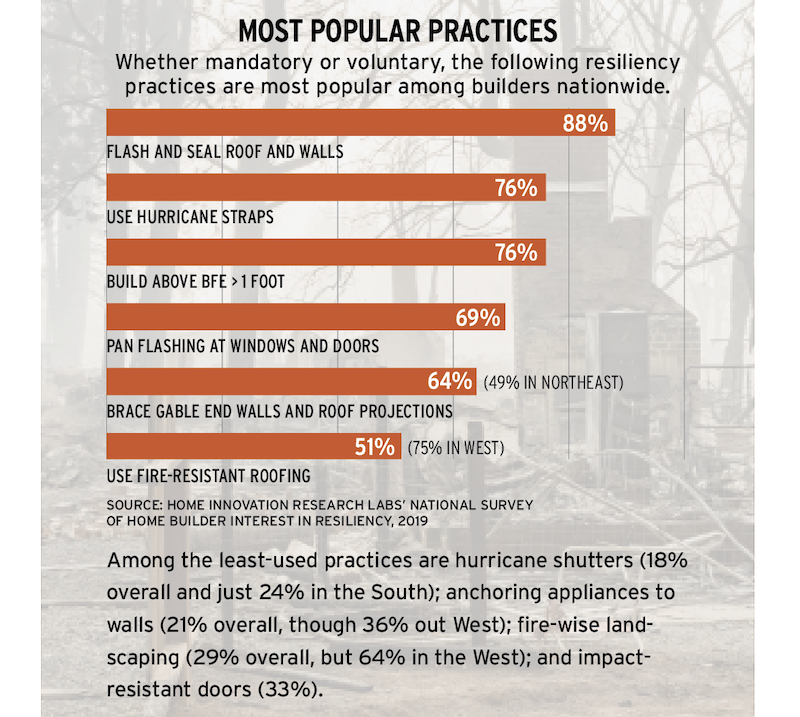

Home Innovation’s study also found that, nationally, more than half of builders practice six of the 20 resilient construction details proposed in the survey (see Most Popular Practices, below), namely following Cope’s advice to protect against wind-driven rain, but also including raised foundations at least a foot above the base flood elevation (BFE), improved window and door flashing and sealing, bracing gable-end walls and roof projections against quakes and storms, and using fire-resistant roofing to limit the damage and spread of a wildfire.

Those results vary by region and their respective prevalence of events (floods in the south, fires in the west), and also represent both mandated and voluntary action by builders.

Other seemingly “low-hanging fruit” that’s nevertheless neglected includes elevating and securing water heaters and outdoor HVAC equipment (which serve well in seismic, flood, and high-wind events), reinforcing garage and double entry doors, and anchoring appliances to walls to keep them in place during an earthquake. Very few apply hurricane shutters, even in the South.

Then there’s Houston-based David Weekley Homes. Even though the production builder/developer has yet to have any of its homes flooded or blown out, for the past two decades it has provided “detention” measures in its communities, namely catchment ponds that slowly and harmlessly release excess rainwater, says CEO David Weekley.

Others go a bit further. Sea Oats Group, a Georgia-based developer, recently broke ground on Cinnamon Shore South, in Port Aransas, Texas, a barrier island along the Gulf Coast. All of the buildings in the 150-acre, $1.3 billion mixed-use subdivision, including 1,000 housing units, will be placed 10 to 11 feet above sea level, says CEO Jeff Lamkin.

With that, all homes and buildings will be bolted every 18 inches around their perimeters, from the sill plate to the top plate, among other framing hardware designed to create a continuous load path against a variety of natural forces.

Resilient Construction and the Code Debate

Cope sees opportunities for builders to explain the risks of natural disasters and rewards of resilience to homebuyers. But don’t expect builders to start marketing resilience as they would stylish kitchens or even energy efficiency. Their responsibility, they say, is to build to existing building codes, which already incorporate resilient practices.

Randy Noel, who owns Rêve Development, in Laplace, La., contends that while “homes built to current codes have survived natural disasters really well, you have to build houses that people can afford.” He doesn’t think builders should feel obligated to build beyond code for resilience and counters that the insurance industry, which is vocal about better resilience, has been less than forthcoming with data that justifies more proactive construction methods.

There’s also the evolutionary track builders have taken to comply with increasingly stringent building codes and regulations that incrementally required greater resilience to wind, fire, rain, and seismic rumblings. “All of the new homes here are sprinklered and have HardiPlank siding,” says Dan Freeman, owner of Lenox Homes, in Lafayette, Calif. “No one uses wood shake roofs anymore.”

Wilson thinks debates about codes and cost miss the bigger picture. “A significant part of resilience is deciding where to build,” he says. “Should we continue building on sites that are vulnerable?” He points to the Dryline project in New York City, which would protect 10 miles of Lower Manhattan from storm surges. That $1 billion-plus project, Wilson says, “may be fine for 40 or 50 years, but the buildings down there are meant to last a lot longer.” What happens, he asks, when water eventually intrudes—a question even more urgent for homeowners in Florida’s coastal towns, which are already more than a little soggy and could soon be under water, Wilson says.

Real Solutions Aren’t Simple

In the fall of 2019, Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), California’s largest utility, strategically cut power in northern and central California, leaving hundreds of thousands of homeowners in the dark. The shutdowns were precautions against high winds blowing down power lines, a circumstance blamed for the Camp Fire. In fact, PG&E was forced to file for bankruptcy protection last year due to its liabilities for that disaster and other recent wildfire events.

Those planned blackouts signaled how responses to potential catastrophes can be driven by fear that errs on the side of caution but also creates its own disruptions. “People are terrified about 2016 happening again,” says Carroll, referring to the flood that deluged Baton Rouge, La., that year. He recalls speculation after that flood about homes in lower elevations being flooded by runoff from communities at higher elevations. “There was no scientific evidence for that,” he says, but it did lead some jurisdictions to restrict lifting homes to more expensive pier-and-beam construction instead of fill dirt, thus slowing rebuilding efforts and raising those costs.

He also regrets that Louisiana missed an opportunity after that flood to engage in a serious discussion about watersheds and drainage-basin maintenance. “No one wanted to have that conversation,” he recalls. “But just charging more in impact fees isn’t going to solve these problems.”

Freelance writer Stacey Freed also contributed to this story.

Access a PDF of this article in Pro Builder's January 2020 digital edition

Read more about resilient construction and home builders' efforts to build more resilient homes:

- Roadblocks to Resilient Construction After Natural Disasters Strike

- Rebuilding After Disaster: A Painstaking Process

- House Lift: Elevating Foundations as a Response to Flooding

- How One Prefab Building Company Is Rebuilding Better in the Face of Disaster