Rolling acres of fully entitled greenfields and favorable zoning that aligns with repeatable plans and existing product provide big production home builders with the predictable budgets and schedules they covet; then there’s the dirt that Trumark Companies buys.

The highly diverse California builder-developer, with offices in San Ramon and Newport Beach, tends to gravitate to land that others won’t touch: brownfields, contaminated sites, lots with difficult land assemblage, and infill, such as a certain vacant parcel in Los Angeles’ Silver Lake/Echo Park neighborhood.

This was as C-level a site as there ever was, located at the end of an off-ramp from a noisy freeway. But the company bought it, and its Trumark Homes division built SL70, a project consisting of 70 contemporary-design, three-story detached homes with roof decks, which sold out in less than two years.

Trumark Homes, which is responsible for 2,200-plus closings since its start in 2008, more than doubled its revenue and closings last year and is projected to finish at $558 million in sales and 559 closings in 2018. Its goal is to be a top 10 privately owned builder with $1 billion in annual sales by 2020.

Risk Taking or Tenacity?

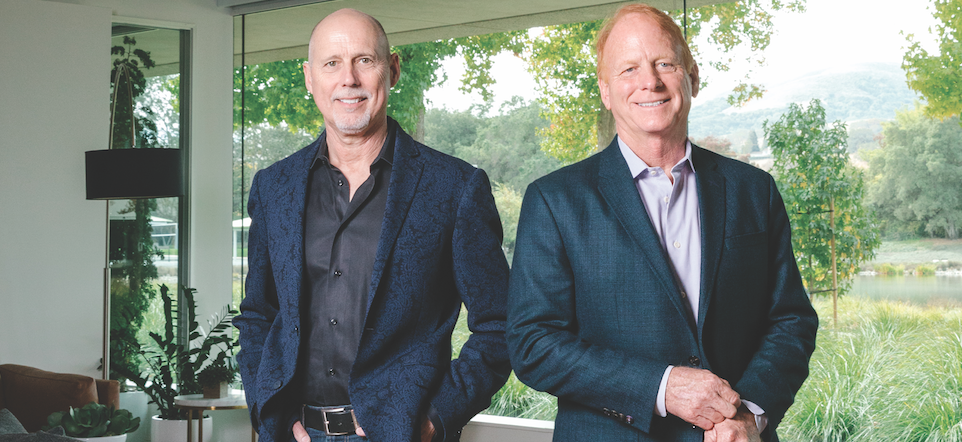

Professional Builder’s 2018 Builder of the Year has gotten as far as it has by anticipating what’s coming next and being correct far more often than not. What others call risk-taking, Trumark co-founders Mike Maples and Gregg Nelson regard as tenacity and creative problem-solving, two of the five core competencies—deal-making, market insight, and operational excellence being the others—that get people hired at Trumark.

This approach has been key not only to fostering the diverse set of skills and experience evident at Trumark Homes, but also in the company’s enviable track record, namely $610 million in revenue across 510 closings in 2017.

“Everything we do is at the highest level of challenge compared with other builders that simply don’t come into this space because it’s such a high degree of difficulty,” says Richard Douglass, president of Trumark Homes’ Southern California division. “That’s where our niche comes in. We can operate in these tougher spaces, I would say, more so because Mike and Gregg have a higher capacity for risk.”

Like other large builders, Trumark Homes builds from a library of floor plans for flats, detached single-family, and townhomes to gain production efficiencies and maximize profitability; that is, unless the parcel demands different.

But, unlike other large builders, Trumark Homes is just one of four companies within the Trumark group, underscoring an approach seldom seen in the industry. That group includes Trumark Commercial, a full-service commercial management and development company that has managed or developed more than 1 million square feet of R&D, retail, and office property since 1996. Then there’s Trumark Urban, which constructs luxury high-rises as tall as 25 stories in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Launched in 2011, that entity has entitled and/or built eight condo projects in core urban neighborhoods totaling 730 units, representing more than $1 billion in revenue.

Finally, Trumark Communities, established in 2013 to entitle, acquire, develop, and manage master planned communities and sell land to builders (including Trumark Homes), has a pipeline of more than 3,100 California lots representing in excess of $500 million in projected revenue.

Seize the Day

Trumark’s opportunity-seizing culture probably wouldn’t exist had Maples and Nelson not almost lost their business in 1991.

The two business school students met at San Jose State University through their involvement in leading Christian youth ministries. Nelson had a family construction background, as his father was a commercial general contractor, and both men owned lots on which they intended to build.

But by the time they received permit approval to build on those lots, the value had increased and buyers emerged with lucrative offers to buy the land. So the two friends fell into entitling land together and then kept rolling the proceeds into the next project. Eventually they also started doing remodeling work and building small subdivisions, planting the seeds of a diverse operation.

Then the savings and loan crisis hit and the ensuing recession forced the partners to sell assets just to keep cash flowing. Among those assets was a 7,400-square-foot spec house overlooking a golf course built in the tiny gated community of Blackhawk, in Danville, east of San Francisco. A professional baseball player bought the house for a couple of million dollars, which was serendipitous at the time because it allowed the partners to pay off a construction loan and a line of credit.

But the buyer was light on cash and asked Nelson and Maples to carry $150,000 of the down payment—a favor he would pay back upon receiving an expected bonus from his ball club. He made one loan payment before declaring bankruptcy, sending the house into foreclosure.

The default crippled the business. Maples and Nelson called their mortgage lender and offered to turn over the house keys. They told investors—mostly friends and family—that they were insolvent. Gregg recalled coming home late from work a week before Christmas to find his wife crying and holding the foreclosure notice that was posted on their front door.

The financial trial heaped stress on their families and tested the two friends’ partnership, as well as their faith. Could one partner depend on the other to have his back? Would the strain tear their families apart? Is God still good?

“There’s a strength there in a relationship with God that is beyond our capability, so we relied on that,” Nelson says. “One of the big lessons we learned is we had to take a day at a time. The experience profoundly reinforced that principle, particularly when God asks, ‘Will you trust me enough to follow me for today?’ Our answer to that was yes because we couldn’t really conceive of how we’re going to even get to the next week.”

The bank instructed the partners to stay with the house and sell it themselves, which they did. They promised investors they would pay back every dime, without knowing exactly how or when it would happen. The investors gave them more time, and one group even allowed Maples and Nelson to pay off principal before current interest.

When the partners saw the market beginning to rebound during the mid-1990s, they recognized a potential shortage of land because too few tentative maps—the last discretionary step required for facilitating land divisions, adjustments, or consolidations—were being approved to satisfy impending demand. They sprang into action, making land buys with credit cards and convincing sellers to accept small deposits. They got land entitled to create value and generated cash by selling parcels to home builders.

Eventually Maples and Nelson paid all of their investors, who in turn became references when the pair courted other lenders for capital. “We learned a lot of skills, like how to problem-solve with people, negotiate, and find a win-win in a pile of mess,” Maples says. “We learned extreme creativity. When you have no money but credit cards, you find ways to make deals work that you wouldn’t think of if you had money to throw at a deal.”

Looking forward is another skill refined from that experience. During the deepest part of the Great Recession, conventional wisdom among investors and builders was to buy finished distressed outlier lots on the cheap. Trumark instead sought more expensive raw land in core markets. The company also returned to building homes to add more value to that land; a reboot 16 years after its initial insolvency. “People want to live in the core areas. They don’t want to live way out in Timbuktu,” says Jason Kliewer, Trumark Homes’ partner and CIO. “What history tells us is the market always comes back to the core areas, and we wanted to be positioned for that. It was a great buying opportunity because we hardly had any competition.”

Still keen to tap into opportunities unseen by others, Trumark managers acted on insight gleaned from Trumark Commercial, namely that office leasing activity was migrating from Silicon Valley job centers to San Francisco, where the employee base could patronize entertainment venues and hip bars and restaurants. Maybe, they conjectured, people would want to live near those places, too.

Even though obtaining planning commission approval to build in the Golden Gate City is notoriously difficult, Trumark needed to get positions there—and enter that market with product more exotic than townhomes and single-family detached. “We had that audacious optimism where we said, you know, if these guys [competitors] can build mid-rise and high-rise, we can build mid-rise and high-rise, and we think we can do it better. We just had to hire great people,” Kliewer says.

The company launched Trumark Urban and, with Arden Hearing then at the helm as managing director, the fledgling division found general contractors and built six projects in San Francisco. Then it looked at a Los Angeles site where a high-rise had stalled during the downturn. The resulting Ten50 project was the first downtown Los Angeles condo development completed in nearly a decade. The neighborhood was flush with rental apartments then, but Hearing saw it burgeoning into a hip scene with art galleries, bars, restaurants, and boutiques. If people were willing to pay $5,000 per month to rent there, Trumark bet they’d be open to buying there as well.

Trumark also was tracking Millennial age brackets, and the consensus analysis during the recovery from the recession was that this potential buyer group was delaying both marriage and starting a family. Additionally, anecdotal observations about Trumark managers’ adult children and their peers suggested those in this cohort who were looking to start a family were considering moving out of the expensive San Francisco core to somewhere more affordable.

The builder further confirmed that theory by interviewing Facebook employees about where they may want to live and what they were seeking in a community. Trumark bought land just outside the core markets and started establishing, as Maples says, “a there there” in Bay Area towns such as Dublin, Newark, and Milpitas. “We believed that once Millennials started getting married and having kids, a large number of them would begin to consider the close-in suburbs,” Maples says. “The California entitlement process is long, thus we began working on many of these projects, anticipating Millennials entering into this delayed stage.”

Trumark also jumped on market research concerning Baby Boomers delaying retirement, noting that when that generation does eventually exit the working world, it will do so in large numbers. Trumark Communities reacted to that opportunity by launching TruLiving, an innovative community model designed for the 55-plus real estate market. The Collective, the first TruLiving community, broke ground in Manteca, Calif., in January of this year. The master plan calls for six neighborhoods with approximately 490 single-family detached homes. Amenities include a pool, spa, gathering spaces, walking trails, and bocce and pickleball courts. In addition, there’s a 10,000-square-foot clubhouse registered under the International WELL Building Institute’s WELL Building Standard, a performance-based system that measures the built environment and amenities for their impact on health and well-being.

Making It Work

So how does Trumark, with 115 employees, have the flexibility to take on such diversity and complexity in products, locations, and buyer targets without having the wheels fall off?

Of course, the company has systems and processes to track the progress of construction scheduling, purchasing, customer care, and everything needed to herd thousands of moving parts toward the finish line. But employees say the key is company culture, which starts at the top. “Mike and Gregg converse with everyone, not just senior managers,” says Tony Bosowski, president of Trumark Homes’ Northern California division. “They’ll walk into anyone’s office or cubicle and talk to them the same way anyone in the organization would do.”

Helping people flourish is a value Maples and Nelson embrace. For example, in a recent leadership meeting, the co-founders asked senior managers from both the Northern and Southern California offices to present an example of someone on their team who demonstrated one of Trumark’s core values. The meeting went long, as division presidents, department heads, and other managers bragged about their subordinates. “At the end of the meeting, Mike and Gregg said, ‘OK, any one of you who said anything about one of your team members, go email them or talk to them, not just talk to us,” CFO Rob Fregulia says. “Talk to your organization and tell them, ‘Hey, I bragged about you today in the leadership meeting because you did an excellent job contributing to one of our core values.’ I thought that was really cool.”

Maples and Nelson’s style is far from micromanaging or issuing mandates. “There’s no one from corporate telling you how to sell, where you should build your sales office, or who your buyer is,” says Carola Cherief, Trumark Homes’ VP of sales and marketing. The co-founders instead ask a lot of questions, and when queries, such as ‘How should we go about this?’ come up, they lead to discussion and team participation.

The approach breaks down barriers in corporate relationships that would typically create a dividing line between manager and subordinate and silos between departments. Junior-rank employees freely seek guidance when they’re unsure about how to tackle a problem. Assistant project managers can make big decisions on projects, says Douglass, and often his direct subordinates bounce ideas off him to gain perspective. “Only 10 percent of the time will I say, ‘I don’t think that’s a good idea,’ so it’s really more of a peer relationship,” he says.

“We’re not public-home-building size with thousands of employees,” Bosowski says. “I think it’s the uniqueness of our philosophy to allow the expertise of people to do what they do best and not pigeonhole.” That sense of empowerment in a flat organization fosters creativity. For example, when Trumark embarks on a new project, a template for marketing or design isn’t merely grabbed from a previous project. Community sales offices are new and different each time. If plans are reused, they’re customized for the project, applying any lessons learned from the previous iteration. For example, some homes at Wallis Ranch, in Dublin, Calif.—a 184-acre master planned community by Trumark Communities—use the same plan as the SL70 flats in Silver Lake built a few years prior, but the Dublin homes include bigger rooms and privacy walls on the roof decks.

Technology also plays a role, and increasingly so. Before models were ready at Founders, in Chino Hills (see case study, left), and Centerhouse, in Ontario, both in Southern California, the sales and marketing team rented kiosks in local open-air shopping malls and showed the homes to passersby using virtual reality headsets and animation displayed on TV screens.

The Founders kiosk opened during early November 2017 and 26 of 76 homes sold before the model opened there in late January. Centerhouse sales contracts were being written that same month, and 33 of 114 units sold before the model opened last April.

“Every single project is a whole new opportunity,” says marketing director Christina Ball. “We don’t have any templates from a sales and marketing standpoint. We really get to merchandise our models fresh and new every time, so we get to specifically meet a market need.”

Collaboration Is Key

Empowerment also fuels collaboration. The sales and marketing team uses its knowledge of product, community, and buyer profiles to assist Garrett Hinds, Trumark’s director of architecture, with design review and architect selection. They’ll go on framing walks with the field team and note changes that should be made in the plan for subsequent homes to boost the product, such as bigger bedrooms or better windows. They work with Purchasing to outfit models, brainstorm with third-party designers so the décor is specific to the taste of a particular target market, and even pick out items for the buyer’s closing gift.

“One thing that helps, from the organizational creative side, is when you come in here you have to be highly competent in your area, but you won’t be exclusively pigeonholed to that,” Douglass says. “We’ll let you touch other parts of the business because it will both help us and help you. You’re going to grow and grow more interested. That diversification keeps you fresh and active.”

Many senior managers previously worked at bigger builders, public and private, and endured cultures that they kindly describe as intense, hard-core, and on occasion inhumane. And while C-level executives at those companies may talk about support and collaboration, Trumark staff note that the extent to which Maples and Nelson walk the talk is obvious. This company, they say, takes a broader perspective and moves forward with a problem-solving tenacity that doesn’t wear them down.

“I think our edge is that we, as a collaborative group, get together, look at land, and are able to understand it and make sure that even if the land price is high, we have the right product and the right build ability and cost of building and trade partners to get the product to work,” says Prem Dhoot, VP of operations in the Northern California division. “When you’re in a big public, it’s all about unit count. How many units can we get in there? How quick can we build?” he adds. “Here, it’s different. It’s the harder projects, the more challenging projects that keep you engaged, keep you interested, and the team working together.”

A Plan for Land

Trumark’s land acquisition process is fairly similar across its Northern and Southern California operations. After the acquisition team identifies property, the land development team steps in to start preliminary studies with the city and engineers.

The land development team also begins working with architects to create budgets and schedules, and Garrett Hinds, Trumark Homes’ director of architecture, huddles with Carola Cherief, Trumark Homes’ VP of sales and marketing.

“Because we’re such a small company, we’re involved in everything,” Cherief says. “They see a piece of land. They come to us. We’ll look at market comps. We go visit it, drive the property, and we give our opinions. We’ll decide together whether to move forward. We’re invited to every architectural meeting.”

In a typical hierarchical organization, salespeople are expected to just sell. Trumark’s sales associates, however, share market insights learned from previous projects that architects should consider, such as including downstairs master suites for hosting family and guests, or tot lots and dog walking areas.

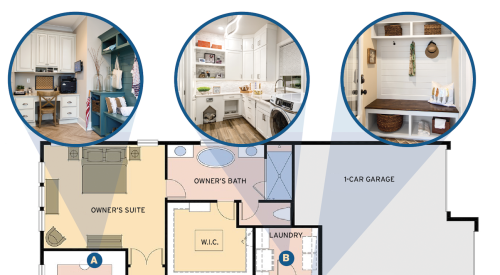

One lesson to be applied to future Bay Area projects is correcting the assumption that a one-car garage is sufficient for a two-bedroom townhouse in a walk-to-public transportation neighborhood like downtown San Jose. Turns out the smaller garage was an obstacle because a price point in the high $900s requires two incomes. If the husband and wife both have to work, they’ll need a garage that accommodates two cars.

Sales and marketing also submits a budget for establishing a sales office and other support for selling the community. Those figures are included in the proposal package assembled by the land development, acquisitions, and finance teams and presented to the company’s land committee, which decides whether to seek more study, renegotiate, pursue, or reject the deal.

Some projects, such as Wallis Ranch in Dublin, Calif., are open land, and Trumark simply figures out what fits there. Others are already entitled with existing plans, and the company puts its own spin on it, as it did with the long-dormant Glass Tower project in Los Angeles that became Ten50.

“We look at any possibility from the entrepreneurial spirit of it,” says Tony Bosowski, division president, Northern California, “and we’re not afraid to take it on. If it makes sense and the market insight tells us that this is something buyers will want, we’ll either figure out how to do it or bring in a person who has done it.”

Building Community

The presence of NIMBYs opposing new market-rate development in San Francisco is as natural as exhaling, and elected officials are wary of going against voters to side with construction companies.

Yet Trumark Urban has entitled every one of its projects there with unanimous approval from the city’s planning commission.

The developer/builder’s approach for working toward entitlement is a unique part of its brand that wins over neighbors, even to the point where they write letters of support for a Trumark development.

“It isn’t a public-builder mentality, where you say, ‘This is how you’re going to do this, and this is what my lawyer is going to tell you,’” says Christopher Davenport, SVP of land development for the company’s Northern California office. “It was really about creating a relationship and coming together to build a partnership toward whatever we were proposing.”

All too common in development politics is NIMBYs showing up at public meetings, while neighbors who don’t oppose the project stay home and go on with their lives. Trumark pursues entitlement by establishing a dialogue with opponents and finding supporters.

“Having worked for other developers and for myself, it’s very rare to have a company that’s strategic and savvy in terms of its business operations in the development world, but also does it with integrity,” says Kim Diamond, Trumark Urban’s newly minted managing director. “We end up building a lot of trust in the communities.”

Unlike most developers that build their projects and leave when all of the units are sold, Trumark stays connected long after the development is done. For example, after reviewing a preliminary design for the Rowan, a 70-unit condo complex in San Francisco, neighbors complained that the building would cast shadows and negatively impact a nearby park. Trumark responded by performing shadow analysis and making adjustments to the design.

That effort resulted in a connection with the community group. In addition, the condo owners, and Trumark employees (including Maples and Nelson) and their families, joined the Friends of Franklin Square for a quarterly park cleanup. Rowan residents pay a $15 monthly fee that funds park improvements, and Trumark has already assisted with establishing upgrades such as a fenced dog park and fitness path.

“We wanted to really emphasize the point that we’re not going away,” Diamond says. “We care about this community and we want the residents who purchased in the community to feel a connection to the park.”

Trumark’s most effective tactic for facing down opposition and finding common ground is listening rather than defending its position, particularly during early public hearings.

“I look at it as a partnership in the sense that we can’t do anything without bringing everybody along,” says Eric Nelson, VP of community development, Southern California. “The minute I fail to recognize a concern or tell someone they’re wrong about their fear is when it goes off the tracks.”

To achieve consensus and support, Trumark has changed elevations and orientation, reduced height, and added features to preserve privacy in its projects. It has engaged neighbors by knocking on doors and offering doughnuts to draw neighboring homeowners in and hear their concerns. The builder has also collected signatures and letters of support for its projects, which it has presented to elected officials so they’re more at ease voting for a Trumark project.

Finding Gold in Chino Hills

Here’s the quintessential Trumark housing project: In Chino Hills, a city of 75,000 in the southwesten corner of San Bernardino County, Calif., vacant parcels that were once the site for trailers housing city hall department offices were rezoned from high-density to medium-density multifamily.

To develop the area, the city required a 15 percent set-aside for affordable housing. Adding to the challenge was that any plan that looked too much like multifamily would meet with resistance from the owners in the surrounding neighborhood of single-family detached homes.

All of those factors combined to make it vastly more difficult to come up with product that would pencil out. Even single-family detached home builders that diversified post-recession into townhouses and low-rise construction saw too much risk in the politics around this piece of property.

They didn’t bid, but the land did attract attention from formidable multifamily and mid-rise developers such as Lewis Acquisition Co. and Foremost Acquisition. And from Trumark.

Time was of the essence, as bidders had just 45 days to perform their due diligence, create a site plan, calculate pricing, and put down a $20,000 deposit that was nonrefundable should the bidder bow out of the process.

Anticipating that the other bidders would propose rows of townhouse-like dwellings, Trumark prepared a scheme that satisfied the city’s request-for-proposal requirements, as well as an alternative plan based on what Trumark’s land team found after reading the entire state statute.

“It was probably the most aggressive thing we had done to date, where we were making commitments without any information,” says Eric Nelson, VP of community development. “We just chose to take the aggressive approach because we really wanted the site and felt we could use the Trumark special sauce to make it different.”

The alternative plan took shape after the land team discovered that the city’s RFP misinterpreted the state law regarding the procedure municipalities must follow for selling public land. They found that Chino Hills could waive the affordable housing set-aside because the city had offered the property to affordable home builders first. Since there were no takers, the land could then be sold for market-rate housing, according to state statute, and the city could assess the winning bidder an in-lieu fee per square foot to fund local affordable housing development.

The Trumark team also read through the city zoning code and found that the definition for single-family attached dwelling specified that at least 4 feet of the adjoining units must be connected to be considered attached. An existing two-story duet plan was modified with larger bedrooms and shared side yards to attract the young professional target buyer. The design also satisfied the attached housing definition by connecting 4 feet of the first-story roofline between homes.

Trumark previously had built in Chino Hills and understood the hot-button issues for city officials. The developer/builder team was confident it could persuade the city council to accept Trumark’s state statute interpretation. They were also betting that a design that didn’t scream Big Condo Complex to the neighbors would sway the votes.

Trumark won the RFP, and Founders in Chino Hills opened in February 2018. The 76 single-family, two-story units blend in with the rest of the neighborhood because, from street level, they look detached. As of November, all but two units were sold.

The Clean-Water Connection

On Trumark’s website, and at every sales office, there’s messaging about the company’s outreach efforts to bring clean water to impoverished people through an initiative that Trumark homebuyers are also encouraged to join.

The company supports Charity: Water, a nonprofit organization that drills wells to provide clean, safe drinking water to people in developing countries. For every 50 homes Trumark closes, the developer/builder funds well construction to deliver water to 200 people through Charity: Water.

Trumark co-founders Mike Maples and Gregg Nelson have each traveled to South Africa and Kenya and seen the plight of women, children, and men walking miles from their villages to draw and carry heavy containers of water back for their families.

To encourage homebuyers to participate, Trumark places virtual-reality headsets at sales offices and has web video that shows how the life of a young Kenyan girl was affected by the need for water: She had to stop attending school so she could make her daily trip to a well and take care of her younger siblings. The video also shows how a new well in the village changed the girl’s life, enabling her to pursue her goal of attending a university.

The co-founders had been privately contributing to the nonprofit before deciding to add more impact to their efforts by making Charity: Water a company campaign. “Maybe it doesn’t do a lot, but we think it at least raises awareness of the connectivity of all of us as a human race,” Nelson says.

- Access a PDF of this article in Pro Builder's December 2018 digital edition