In an ideal world, a new-home builder would have an unlimited budget for constructing a properly sealed building envelope that renders air leakage obsolete. Unfortunately money is tight and the typical single-family detached residence has nearly one mile of joints and openings that leak air and allow moisture, cold drafts, and noise to enter the home. The builder with a limited budget can’t seal every nook and cranny, so the question is, which leaks matter the most?

Which joints to seal first if you want the biggest impact for the smallest investment

To find out, Owens Corning conducted year-long research, taking thousands of measurements on wall and ceiling assemblies subjected to controlled conditions in its laboratory as well as in a ranch-style house after it was sheathed, house wrapped, and clad with modern building material. The project measured the leakage rates of 17 common house joints, then ranked which ones builders could seal—if sealing all joints is not possible—to get the most benefit in order to pass a

blower door test.

“As we encountered builders with a limited budget, it begged the question: ‘I only have X dollars to seal this house; what joints should I apply (sealant) to to get the biggest benefit?” says David Wolf, Owens Corning’s senior research and development program leader. “Nine times out of 10, when they’re asking about the benefit, they’re asking about a blower door result. That caused us to ask the question, “Which joints would you seal first if what you are trying to accomplish was the biggest impact on a blower door result for the smallest investment?”

Joint Sealing: Most Effective

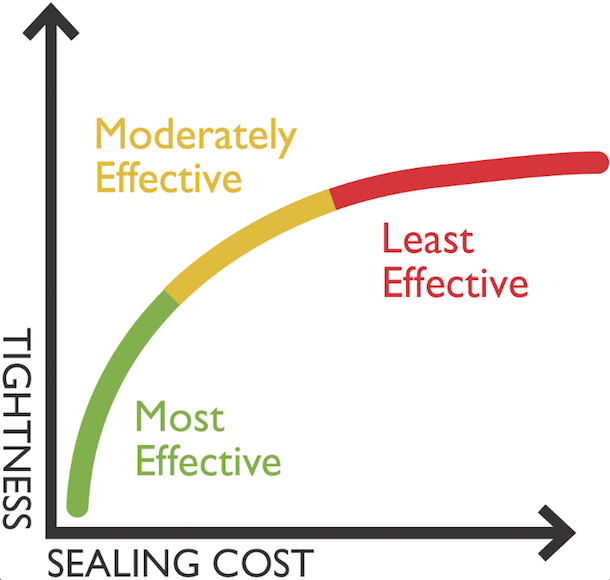

Conceptual graph of the biggest bang-for-the-buck approach to air sealing where the most effective joints to seal are those that offer the largest amount of enclosure tightening with the least amount of linear footage of applied sealant.

Conceptual graph of the biggest bang-for-the-buck approach to air sealing where the most effective joints to seal are those that offer the largest amount of enclosure tightening with the least amount of linear footage of applied sealant.

Some of the rankings are obvious. For example, builders already know that recessed lighting and duct boots are prime air leak culprits. But the study results enable builders to take their budget for sealing, measure how many feet or units of particular openings are in their house, and use the unit leakage rates to select the biggest problem areas that they can seal to the greatest effect so their house will be energy-code compliant.

During the data gathering phase of the study, the Owens Corning research team approached the Environmental Protection Agency and asked whether the agency knew how much air actually leaked from the top plate-to-attic opening. The EPA had added sealing that joint as a new requirement for Version 3 of the Energy Star standard, which was fully implemented on Jan. 1, 2012 (see “Earning the Star,” PB April 2013, or ProBuilder.com). The agency didn’t know exactly how much leakage occurred but assumed that the opening was one of the top offenders for compromising air tightness.

“They made a recommendation based on gut feel, which turned out to be a really good recommendation,” Wolf says.

RELATED

The Owens Corning research confirmed the Energy Star assumption. Leakage from the top plate to attic was considerable, 0.03 to 0.7 CFM50 per foot of joint and approximately 0.03 to 1.6 ACH50 for the whole house result. The study states that the average-sized house can have more than 500 feet of this joint. The size of the gap between the drywall and framing at this location can be relatively large due to misalignment in framing (stud-to-plate) or the presence of top plate-to-rafter ties (hurricane ties), which can create a localized offset of 3/16 to 1/4 inches between the dry wall and plate.

Other openings ranked most effective for sealing are band/rim joist joints. These openings are the only wall joints that are not meaningfully constrained by drywall, so once air passes the exterior skin associated with a band joint, it typically flows to a large, open space in the floor system and travels unimpeded. The top and bottom of the band opening leaked an average of 0.86 CFM50 per foot, which results in about 0.4 ACH50 for the whole house result.

The

garage-to-house common wall is another opening ranked as most effective to seal. It leaked an average amount of 0.6 CFM50 per foot of joint, resulting in approximately 0.1 to 0.3 ACH50 for the whole house result. Whole house leakage was not as large as the per foot basis because there are not many feet associated with a garage wall. But addressing this joint is critical for

indoor air quality since toxic gases can travel to the connected living space. This joint leaks more because the exterior wall separating the living space from the garage space is sheathed on the exterior side with drywall. The material has less stiffness than OSB or plywood, which adversely affects the air tightness of the joint that forms between the drywall and the framing members.

Joint Sealing: Moderately Effective

Top plate-to-attic—The red arrow depicts the inward leakage path.

Top plate-to-attic—The red arrow depicts the inward leakage path.

The study found low leakage rates from the top and bottom plate-to-sheathing joint and the bottom plate-to-subfloor opening—areas graded as moderately effective candidates for sealing. The plate-to-sheathing joints, both top and bottom, leaked an average range of 0.07 to 0.6 CFM50 per foot, resulting in 0.04 to 0.4 ACH50 for the whole house.

“What you notice from our results is that joints in the wall are not on the top of the list,” Wolf says. “That, for most people including myself when I first saw it, is counterintuitive. You would think since there are lots of joints in the wall, it must leak a lot.”

What happens is once air passes the exterior skin associated with this joint, it must pass the interior skin by moving through electrical outlets and switches, plumbing fixtures, and the bottom of the wall, windows, and doors. But drywall plays an unintended role in air sealing, as there are more joints and openings that allow air into the wall cavity than there are openings in the drywall to let it out. Also helping is that a painter or a finish carpenter inadvertently seals drywall penetrations with baseboard or caulking for aesthetic reasons. Yet such caulking typically has low flexibility and will eventually crack and compromise air tightness.

“We knew wall joints leaked less, but now we know why,” Wolf says.

Building code officials and builders require the bottom plate-to-subfloor joint to be sealed. But the Owens Corning research shows it leaks a tiny 0.1 CFM50 on average and up to 0.1 ACH50 for the whole house. “It is possible that this joint can be quite large/leaky in some localized cases where the wall is constructed on the floor, tilted up into place, and potentially have some construction debris lodge between the bottom plate and the subfloor. While this is an uncommon occurrence, the joint obviously should be sealed in this case,” says the company’s white paper.

Joint Sealing: Least Effective

Recessed lights can leak an appreciable amount of air between the light housing and mounting flange (red arrow 2), and between the mounting flange and dry wall (red arrow 3). Leakage through the light housing is fairly tight as required by many building codes (red arrow 1).

Recessed lights can leak an appreciable amount of air between the light housing and mounting flange (red arrow 2), and between the mounting flange and dry wall (red arrow 3). Leakage through the light housing is fairly tight as required by many building codes (red arrow 1).

Corners, window and door framing-to-sheathing, vertical sheathing joints, and joints between exterior top plates were the openings rated as the least effective candidates for sealing. Leakage rates were small because these opening have a small amount of overall joint length, a small amount of leakage and/or the leakage was blocked somewhat by drywall. While sealing a corner will not have much impact on a blower door test, doing so can affect thermal comfort, particularly if homeowners will have a chair or a sofa in that spot where they will spend a lot of time reading or watching television. Each corner has three separate leakage joints so addressing this area calls for three feet of sealant for every one foot of corner, Wolf says.

Another opening assigned to the least effective group is the bottom plate-to-slab joint. The study didn’t actually measure leakage rates for this joint as the ranking is based partly on the low leakage rates for the bottom plate-to-subfloor opening; and also because the bottom plate-to-slab connection usually has two advantages related to air tightness. First, the slab typically is smooth due to the need for uniformity for finished floors. Second, the framer often seals this joint already with a sill gasket sandwiched between the bottom plate and the slab.

“We still recommend that all joints be sealed; however, we recognized that there was a practical limitation that builders, in their heart of hearts, might want to seal all openings but just don’t have the budget to be able to do that,” Wolf says.