If it's a fair assumption that leading economists are right, and the building and real estate boom has peaked — and at some point, normal economic cycles will bear this out — builders will be looking for new opportunities to turn a profit. For those not currently in the business, land development remains a viable alternative that, handled correctly, can bolster the bottom line.

There's no single formula for success at finding, controlling and entitling land. Even for the same builder with a relatively unchanging portfolio of plans and fixed overhead, the vagaries of location, location, location can wreak havoc on profits if up-front due diligence isn't conducted properly. And while the steps of such research can be easily found in books, there's no substitute for experience.

Nonetheless, some truths are evident:- Available land is getting harder to find.

- Opportunities exist in overlooked locations.

- Sound financial control equates to smart land control.

- Creative minds can overcome almost any obstacle.

This is true for builders in the hilly Northeast, the deserts of the Southwest and the blighted neighborhoods of once-great urban centers. We've spoken with builders in each of these environments, and they have shared their experiences on finding land, controlling it with a fair financial arrangement and obtaining entitlements — simply defined as the right to create lots and build on a piece of land.

Hill, Desert, BrownfieldBuilders looking to enter into development can find success in various ways, as the following three companies illustrate.

The Green Company: In Plymouth, Mass., Alan Green and sons Dan and Tony of The Green Company became a development partner and the first builder at The Pinehills, a mixed-use master plan currently hosting 10 builders on a 3174-acre parcel with 2983 homes. Partnering provided the builder access to resources for a time-consuming zoning rework from 1700 grid-subdivision homes to a denser and more profitable plan that preserves 70 percent of the parcel's land for open space while creating views by nestling homes into hilltops and moraines rising hundreds of feet.

Tony Green divested his building interest early in the game to become managing partner in The Pinehills LLC, and risk developing "something different." The risk paid off; in July, the community closed its 600th home, with 180 in backlog and 20 more reserved, not to mention 100 renters and considerable non-residential users. Housing prices average $565,000, about $200,000 above Plymouth's norm.

The Green Company sold all 43 homes in its first neighborhood in less than two years from model opening and proceeded to sell 117 and 119 homes, respectively, in the last two years at its second, the 550-townhouse Winslowe's View.

TransWest Housing: In Southern California, Jim Wait joined forces in 1984 with Barry McComic, CEO of TransWest Housing. After weathering the lean years of the late 1980s and early '90s, the company established itself in San Diego and Riverside counties. It is currently experiencing a boom, even as the national Giants increase their area holdings. The company sold $40 million with 81 closings of single-family homes last year and expects $190 million on 81 closings this year, according to Wait, treasurer and chief operating officer.

Land-related factors have everything to do with the growth at TransWest. "In 2004, we were in the process of building all those units, but we hadn't quite closed them yet, Wait explains, noting that "to get from the entitlement stage through completing a house to sell to a consumer takes anywhere from 18 months to three years." In addition to balancing the company's land position and its profits against sales velocity, he says the company is moving northward and inland with a new development in San Bernardino. It is also researching opportunities as far north as Sacramento, inland and outward to Reno, Nev., to compete as the national Giants move into TransWest's traditional market area. The company is also considering urban infill with denser mixed-use products and development in blighted areas of larger cities, which will bring a new construction discipline into the company's field of opportunity.

Westrum Development: John Westrum, chief executive officer of Westrum Development Co., based in Fort Washington, Pa., knows a thing or two about the transition from suburban greenfields to urban infill. Westrum was already in developing and building 300 homes a year in southeastern Pennsylvania when he decided to change directions in 2001 and sold all of his suburban assets to Pulte Homes (just weeks before Pulte acquired Del Webb's active adult empire). The transaction consisted of 3,000 residential lots, approximately 1,000 of which were entitled.

Westrum was essentially in the entitlement business for the next three years, as he entitled and sold the remaining 2,000 to Pulte. Following the sale, he returned to building, but with a new, exclusive focus on urban redevelopment. He currently has land for more than 10,000 housing units in the pipeline and this year forecasts 175 closings to net more than $100 million. Parcels in various stages of development are located in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, Michigan and Illinois, where he is working on a 6,000-unit development at a former U.S. Steel plant along Lake Michigan on the south side of Chicago. His reputation has put him in ventures with other builders including K. Hovnanian, and landed him a spot on the Pennsylvania State Planning Board and the chairmanship of a revitalization committee under Gov. Edward Rendell.

Finding LandThere's no end to the list of factors builders must consider when seeking appropriate land for development. Market research on available land, geotechnical and environmental factors, market demographics and competitive offerings barely scratch the surface. Large production builders pay thousands of dollars each month to stoke their production fires. Smaller builders who truly know their markets can forego some of the formalities and use their instincts to close in on a deal more quickly. But builder-turned-developer Tony Green of Pinehills LLC recommends that even small builders who forego more complex processes ask themselves three critical questions:

- What do people want to buy?

- Can you actually build what people want to buy?

- Can you actually build what people want to buy on a particular piece of land?

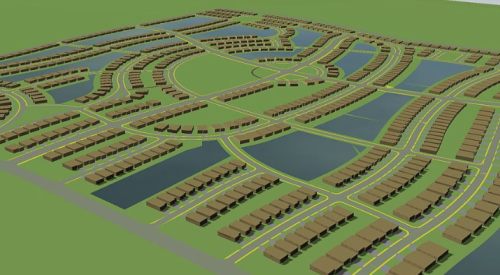

It's significant and appropriate that the emphasis is on what buyers want. Builders who have a single-product type need to adjust their sights — and, literally, sites — on land and markets appropriate to their production capabilities. Beyond actual product, site amenities from water features to golf and other recreational features and sight lines are just some of the considerations. Sight lines are especially critical where density is high, and they can be managed by lot/house orientation, window locations and site improvements from trees to ridgelines. "Big views don't necessarily mean big yards," says Tony Green. Whether or not a particular house plan is right for a lot may involve these factors as well as entitlement issues that may arise.

Beyond researching, finding land relies on any number of relationships, including personal contact with prospective sellers, industry developers and builders, as well as business relationships with brokers and specialists. Called contract purchasers in some markets, these individuals will buy, entitle and "flip" land to interested buyers. They will also sometimes serve as development investors.

The Green Company prefers word of mouth. Dan Green, vice president, notes that there's some science and expense to creating a climate for this to occur, citing the company's brand advertising — not just product. In addition to building an image with consumers, this advertising is also a way to "keep our name out there among the land-owners, too," because some of the best but hardest-to-reach sellers are those who "don't want too much attention in the brokerage community and don't want their name plastered all over town." This subtlety can also give the builder-developer time to think and plan a course of public action before the deal is put under the microscope of public scrutiny.

Builders can, of course, work successful deals with brokers — that's what they're paid to do — but to seal a good deal, Trans West's Wait says, "you have to act quickly and make quick decisions."

Controlling the DealWhen Lennar's U.S. Home Corp. put a 170-acre site in the Hidden Canyon master plan in La Quinta, Calif., on the selling block, TransWest was the first to see this Riverside County property and immediately put it under contract. The builder "got as long a due diligence period we could get," says Wait, who negotiated a 90-day period - twice the usual. After that period, the builder put an additional sum into escrow — somewhere between $50,000 and $100,000 is common for such deals — and had 45 more days to close on the property or lose its investments thus far to the seller.

Instead, TransWest closed and after 18 months of entitlement to turn tentative maps — "plats" — into approvals for 169 homes on 70 buildable acres. (The other 100 acres are in the mountains.) Models opened last November, showing two product lines: 1) Ridge Gate, starting in the $800,000s; and 2) Ridge View, slightly smaller in both size and price. As of mid-July, the project's 52 closings and 82 pending contracts translate into a sales velocity 1.5 to 2 times the area norm, appropriate product, and a "unique location that is highly desirable," says Wait.

While small builders aren't likely to buy land outright, Westrum did so in putting in a high bid of $5 million and change for an abandoned, 27-acre naval officer's housing complex in Philadelphia, which would become The Reserve at Packer Park. Westrum uses various mechanisms for his projects elsewhere, and in certain cases flips entitled lots to development partners, including K. Hovnanian, NVR's Ryan Homes and Richmond American.

More common are options arrangements, which can be structured to meet the needs of both buyer and seller. Sometimes a seller, such as a smaller, private landowner, trusts the builder-developer and wants to be an investor, which may or may not suit the builder-developer. "You have to look at it from both perspectives," says Tony Green. For instance, the seller might not want to risk special terms, let alone invest or entertain an offer from a first-time developer. The Green Company's smart move was to join a team with experienced partners. For instance, The Pinehills LLC's deal allowed it to purchase future, contiguous land under specified time and price, which so far has led to the addition of roughly 100 acres to the original plan, with more likely in the pipeline.

The development team locked in a contract involving a "roll-up note" that provided a deposit and due diligence period with no interest costs. Under this arrangement, the interest on "up-front" monies roll-up into the principal, says Green, "so there's actually no payment out of pocket until it's time to pay the note." That "float" can then be used for due diligence and the entitlement process.

Entitling in Perspective"There's so much more to the success of a development project than how you structure the deal," says Dan Green. While he says a bad land deal will make it "very difficult to recover and become profitable," the key to entitlement is "how creative you are in the permitting process," which can take years.

Brother Tony on the development cites "an inherent connection" between controlling and entitling land, and adds, "What you're really trying to make work is the entire process of deciding who is going to buy from you, and what it is you're going to do with a piece of land to attract them."

Part of that process may include convincing skeptics that a plan that veers from existing zoning can be a benefit to all. Toward that end, The Pinehills team conducted community and market outreach early and often, from its first 1997 public presentation of topography and habitat surveys — and a visit by golf legend and course designer Jack Nicklaus — to tours given to hundreds of community members to show the benefits of a view-based approach.

Why would a builder-developer risk a longer entitlement process to change zoning? The result can be more attractive to the community and buyers, even in higher-density plans that can create higher profits.

TransWest, which often buys land at the tentative map stage, still prefers raw land despite the unpredictability of entitlement periods, which for its projects range from 18 months to three years. One hedge against the risk of a drawn-out process, explains Wait, is that coastal land inflation is still in the 20 percent range, despite some signs that the boom years are leveling off: "If a governmental agency holds us up for six months, they end up making us a bunch of money in an inflationary time." But the developer has to maintain cash flow and can't sit on land indefinitely without other projects in progress.

Wait warns builder-developers against getting lazy about their financial controls, because settling for a 10 percent gross can easily put a company into the red if the market goes flat. "If I sold a house for $100,000, that means I've had to pay for my land, all supervision, engineers, architects, carrying/loan costs, city fees. In addition, as the builder, I pay a three or four percent management fee to the developer; in this case, our development side. After all that, there's 10 percent — $10,000 — on the table to split between the partners. And by the way, my business must live on that 3 percent to 4 percent of sales management fee."

Obviously, the numbers are higher, but the example shows that a builder-developer has to maintain overheads by setting profit requirements and working backwards. If those numbers aren't met, it's likely something's wrong with the product or pricing in relation to the land's value.

On the urban front, cities are hoping to lure redevelopment, but Westrum says one-shot lots are riskier than larger parcels, which can bring "critical mass...You can't go into the kinds of areas we do and expect to have high profitability until you change the area and really change the landscape. To do that, you need large-scale property."

Builders must also control added costs when working in union cities. Westrum contained improved lot costs below 20 percent, lower than average for many builders even in suburban greenfields. An added benefit at his Reserve at Packer Park was that re-use of infrastructure, including foundations, helped speed entitlements. "If you want to change a neighborhood, you need staying power, professionally, financially and mentally," he says.

Comparing greenfield to infill projects in Philadelphia, Westrum quips, "in the suburbs, they know how to deal with you from an entitlement and zoning standpoint; they just don't want to deal with you," while the city "wants you to be there, but doesn't know how to deal with you...but things are changing. Five years ago, there were 200 housing units built in Philadelphia. Last year, there were 2,000."

No matter what kind of development you might be considering, remember that the point isn't to secure a permit but to provide a value to the market and community, while turning a profit. That requires a good understanding of the balance between land, product, and market.