| NewDay Development job superintendent Michael Lourenco appreciates the trust he and owner Louis Krokover share — Lourenco’s decisions are not questioned. |

As our grandfathers told us, “Trust is something to be earned. It’s not a right.”

Not necessarily so, says Marian Wright, who has worked in human resources for builders for 17 years — most of them for David Weekley Homes in Houston and now as a consultant. Her one-person firm, Strategic Human Resources Development, helps companies assess their current situation, formulate a plan to build and foster trust, and maintain an environment that supports that trust.

“Trust certainly seems difficult to quantify,” she says. “It is something you have to inspire and demonstrate, and it has to be demonstrated from the very top down to every employee.”

Wright says the first step is deciding on core company values, preferably with employee input, and then communicating them consistently and frequently. Next, live out those values in business decisions and day-to-day behavior. Finally, employees need to know what’s expected of them regarding those values. Clear expectations reduce guesswork.

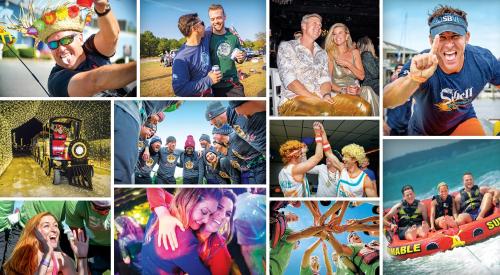

Certain values are vital components of trust at these 101 firms: respect, fairness and pride. Camaraderie among employees who know each other and enjoy working together supports that trust.

Judy Litov left a home building company more than 20 years ago swearing she would never work for another. Louis Krokover, owner of NewDay Development, a custom home building and re-modeling company in Encino, Calif., convinced her to work for him, promising things would be different. Litov has been with him ever since and enjoys a high level of autonomy as office manager. “Nobody looks over your shoulder. Nobody tells you what to do,” she says.

Despite her diverse job duties, Litov says it always has been clear what’s expected of her and her position. She and her manager communicate directly daily, and she meets informally with the crews at least twice a week to give and receive job updates and “make sure they’re happy.” She also can work from home, depending on a task’s requirements.

| Although not the original intent of the Florsheim Brothers Foundation, started by David (left) and Bob Florsheim, employee pride in Florsheim Homes has increased through volunteer work. |

Michael Lourenco, a NewDay job superintendent for three years, has owned his own company and worked for companies large and small during the past 22 years. He has run the gamut in job autonomy and says he has real authority at NewDay. “I can make decisions on the job site and not have to question whether Krokover is going to accept them or not. We have faith in each other and work through problems.”

Lourenco concedes that building that trust was a process but says it was enhanced by NewDay’s approach to good decisions and mistakes alike. Mistakes are understood to be part of the work. “Everybody is human, so no one holds it against you,” he says.

Litov and Lourenco agree that, although few employees move around within the company, Krokover’s approach to position changes is fair. “If you do the job well, it’s yours,” Litov says. Lourenco adds that the ability to take on a new position depends on merit and knowledge, with the explicit understanding that if an employee has the interest but doesn’t have the knowledge, “[Krokover] is more than happy to help you get it or teach you himself.”

Likewise, Krokover is willing to learn from employees, broadening the atmosphere of trust. Lourenco once suggested using roof trusses rather than the beam and stick framing with which Krokover was familiar. “He was willing to try it out, and we made money and saved time,” Lourenco says. “He’s wide-open as far as getting suggestions.”

Sivage Thomas Homes Inc., a production builder based in Albuquerque, N.M., with additional operations in Phoenix, has similar openness. “The Sivages, Mike and Kevin, are involved in the day-to-day operations to the point that everyone who works here is on a first-name basis with the company owners,” says Robert Lupton, director of planning and site development. “You can talk to Mike or Kevin whenever you want. They have a personal and professional commitment to you, and you have the same commitment to them.”

| Fun with fellow employees outside of work helps everyone at Dominick Tringali Architects, including project manager and junior associate Mark Garagiola (center), form friendly, productive working relationships.. |

Lupton and other Sivage Thomas employees also have a manager who models what Wright calls a key component of respect: work/life balance. Company president John Hardin is a Little League coach. During the season he has what Lupton says amounts to a split shift: He comes to work, leaves to fulfill his coaching responsibilities and then re-turns to finish his workday. This helps employees see it’s OK to balance personal commitments with work.

Pride is another component of trust because employees who believe they are part of a quality product are proud of what they do and of their company.

Florsheim Homes in Encino, Calif., which will build 300 homes this year, shares customer-satisfaction data with employees monthly via e-mail. The survey results break down into five categories — sales, mortgage, construction, customer service and overall satisfaction — and Florsheim rates itself against data from previous months, noting improvements or problems.

Audrey Pritchard has been with Florsheim for eight years. As the escrow and marketing coordinator, she has little direct contact with customers, so the company feedback keeps her connected. But she says that what makes her most proud is seeing completed homes.

“I just kind of well up with tears because they are so beautiful,” says Pritchard. “We really do build quality homes, and we take time planning how the neighborhoods should look.”

Florsheim also has a strong although fairly informal charitable giving program. “If you’re in business you get solicited for donations all the time,” says Bob Florsheim, who runs Florsheim Homes with brother David. It had gotten hard to keep track of it all, so David formed the Florsheim Brothers Foundation, which raises money and channels it to charities that help kids. All but two members of the foundation board are Florsheim Homes employees.

Employees volunteer their time, so all money raised goes to the charities. “We have a golf tournament every year and a steak and oyster dinner, and it’s all employee-donated time to put these things on,” says Bob Florsheim. “David and I contribute, but the employees make it all happen.”

Dominick Tringali Architects in Bloomfield Hills, Mich., builds trust not just from the top down and bottom up, but also laterally. As a result, employees say they feel they are among friends, blurring the line between work and fun.

“We’ve always attempted to set up three to four outings a year,” says vice president Jeff Ziegelbaur. There’s also a company softball team.

“You get to enjoy the company of your peers in a nonwork environment,” says Mark Garagiola, project manager and junior associate. “I get to know them better, and that makes relationships run more smoothly. You never see people at this company standing by the door ready to split when the 5 o’clock bell rings.”

Garagiola says president Dominick Tringali strongly supports the camaraderie by combining it with work-related outings as well. Employees go see each other’s work or visit homes designed by competitors and critique the projects.

Fostering camaraderie can enhance teamwork and effectiveness. Part of Garagiola’s and Ziegelbaur’s jobs is to mentor other members of the firm, but all employees strive to help each other.

“That’s the greatest part of our company,” Ziegelbaur says. “If someone is in a hole and another person isn’t under deadline, they’ll jump right in and help that other person out. It makes the company work better, and that’s the objective.”