When Gerry McCaughey talks about the standard housing construction methods in the United States, he sounds astonished—and not in a good way. He uses words like “ridiculous” and “lunacy” to describe the inefficiencies of on-site, stick-frame construction.

McCaughey’s company, Entekra, takes a different approach: offsite construction. “Europe has a very clear understanding of what offsite construction is,” the Ireland native says. The United States, he adds, does not. But that might soon change, thanks in part to Entekra. For its innovative approach, Entekra this year won the Ivory Prize for construction and design.

McCaughey’s father, Brian McCaughey, started Ireland’s first offsite construction company more than five decades ago. In the 1980s, Gerry and his brother, Gary, co-founded Century Homes, which became Europe’s largest offsite builder. After spotting an untapped opportunity stateside, the McCaughey brothers, in 2016, launched Entekra, where Gerry serves as CEO and chairman and Gary as senior vice president, supply chain.

In the U.S., Gerry McCaughey explains, stick-frame construction has long ruled the housing industry. Its advantage is its flexibility: A builder can make last-minute adjustments on site.

But the disadvantage is its inefficiency, plus the difficulty of guaranteeing high-quality on-site standards. On the other end of the construction spectrum is modular. Its advantage: it is factory-made so it can meet quality standards. But the disadvantage is its lack of flexibility.

“We sit in the middle,” McCaughey says. “The reason offsite construction has not made further progress in the United States is there’s a misunderstanding here of what it’s about.”

—Gerry McCaughey, CEO and chairman, Entekra

The Entekra Housing System

For Entekra, offsite is about using technology to bring the antiquated U.S. housing industry into the modern age. It’s about delivering not only prefab parts of a house, but a holistic system to ensure that construction is as efficient as possible. “We say, ‘If it’s not a system, it’s not a solution,’” says McCaughey.

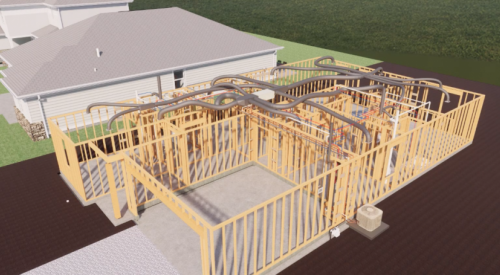

That system, called the Fully Integrated Off-Site Solution (FIOSS), begins with a rigorous design process that uses computer-aided design (CAD) software and involves the builder, architect, engineer and any contractor who will work on the house. When a builder first comes to Entekra with an architectural plan (the company does not work directly with homebuyers as of yet), Entekra right away identifies and eliminates any of the design’s too-common inefficiencies and inaccuracies.

One inefficiency in particular astonishes McCaughey. It’s architects’ use of the term “field verify” on their drawings. Architects use the term to indicate that they cannot confirm a dimension or another design element, so they leave it to someone in the field to confirm it. And that introduces a lot of uncertainty. “It’s a ridiculous situation,” McCaughey says.

Another commonly accepted inaccuracy that rankles McCaughey is the use of measurements that aren’t what they say they are. A “2x4” piece of lumber is actually 1.5 x 3.5 inches—a reflection of changes in lumber production over time.

“I cannot name any other engineered product that has dimensions that do not reflect its actual size,” he says. “It’s absolute lunacy.” Such inefficiencies also lead to more rework, he adds.

After correcting the architectural drawings, or sometimes providing the drawings itself, Entekra looks for cost savings in materials, delivery, assembly and construction. It’s an iterative process involving close collaboration with the builder, architect and engineer.

Once that process is complete, Entekra asks the builder to convene all the tradespeople who will work on the house—the concrete layer, plumber, electrician, HVAC technician, tiler and so on—so that Entekra can solicit any of their concerns and address them in its design.

For example, Entekra’s 3D laser scan of the house’s slab helps the concrete layer determine exactly how many pounds of concrete will be needed. Or Entekra might foresee that an HVAC duct will run into a beam. So it enters that data into its software and collaborates with the HVAC technician and builder to come up with an answer—such as using Entekra’s computer numerical control (CNC) equipment to cut the necessary holes so that, when the house is erected, the duct run is fully in place.

By the end of this thorough design and engineering process, which takes six to eight weeks, Entekra has identified and addressed any issues—before it cuts the first piece of timber.

“Our view is it’s a hell of a lot cheaper to work out any problems on a computer screen than it is on a building site,” McCaughey says.

Then, at one of its two manufacturing plants in Northern California (it plans to build a third in Southern California in the near future), Entekra uses automated equipment to fabricate the walls, floors, stairs and roof trusses—measuring and cutting each to an impressive degree of accuracy and with minimal waste. Entekra then delivers the components to the site, where the builder assembles them all like a jigsaw puzzle.

At its newer plant, Entekra can produce 3,000 single-family homes (2,500 square feet in size) in a year.

The ROI of the Entekra approach to homebuilding

It takes an average of four or five days from the first delivery of the house’s structural parts to the time the frame is ready for the electrician, plumber and other contractors. By comparison, that process takes a stick-built house in California an average of 17 days, McCaughey says. Plus, the longer it takes to build a house, the more it costs.

From start to finish, every extra construction-site day costs a California builder on average an extra $1,000, McCaughey says. For McCaughey, such cycle-time savings offset Entekra’s higher cost of about 5 percent more than stick-frame construction.

Offsite provides other savings. Entekra delivers only what the builder needs each day, nothing more, so there’s little waste—and there are no materials lying around, waiting to be pilfered. And there’s no need for large dumpsters that can cost several hundreds of dollars.

As pandemic-minded buyers grow more concerned about quality and safety, they will think more about how their houses are constructed, not just what they look like, McCaughey contends. One builder client recently told McCaughey that the builder promoted Entekra’s offsite method to his buyers and outsold his competitors. The builder said he would advertise Entekra’s method in his marketing literature.

“That’s unheard of in the United States because usually all people want to talk about are upgraded countertops and upgraded bathrooms,” he says. “But here’s a builder talking about upgraded building.”