When I began writing monthly columns for the home building industry, we were still in the old millennium, I was in my 40s, and Bill Clinton was president. I wondered if the industry would consider me worldly, wise, and sufficiently experienced to have anything authoritative to say, but my first editor did nothing but encourage me.

Ten years prior to that, as a young corporate VP with a major national builder, I was even more sensitive to the “youth thing.” Back then I easily looked 10 years younger than my age and was routinely “carded” until my late 30s. It was a burden—one I’d take back today in a heartbeat.

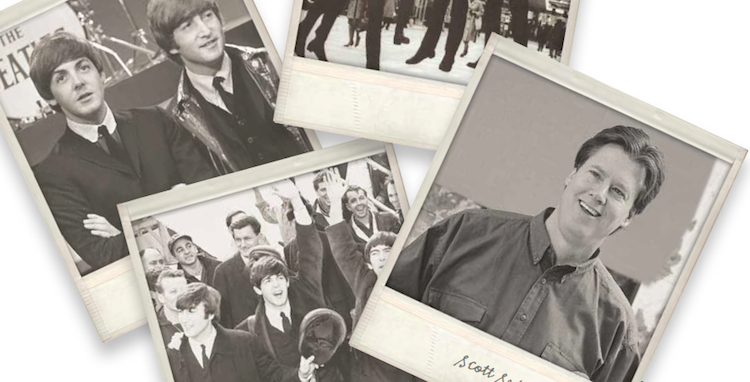

Last week, driving down the highway pondering the topic for the September column, I was listening to the “’60s on 6” station on SiriusXM and “When I’m Sixty-Four” by the Beatles came on. That song was released in 1967 when I was 15 years old, and I distinctly recall goofing around singing it to my girlfriend Becky. The song seemed so absurd to me. As it happened, one of my grandmothers was 64 and I couldn’t fathom ever being that old. All four of my grandparents were essentially retired and mostly they gardened, travelled, and visited grandchildren. To me, that pretty much summed up their existence.

As the catchy tune, written by Paul McCartney, came to an end, it occurred to me that in September, shortly after this column is published, I will turn 64. Suddenly, this silly song took on greater meaning and irony. I found myself singing and wondering, “Will you still need me, will you still read me, when I’m 64?” It’s a fair question, I thought. Will the Professional Builder audience still read my columns when I’m 64, or 70, or 74? Can I stay relevant? And is it enough to just stay relevant, or is there an age barrier that at some point you simply can’t overcome? A troubling notion, to say the least.

The Mentors

I thought back over my life to those aged 64 or even older who genuinely influenced me. There was David Telfair on whose tree farm I worked during my high-school years, especially at Christmas. Besides the tree-farming business, Dr. Telfair was, among other things, a physics professor at Earlham College, a Quaker elder, and a student of the philosophy and physics of chopping wood. Weighing maybe 140 pounds soaking wet, he could two to one out-chop me and others substantially bigger and stronger, without breaking a sweat. He would just study something until he fully understood it, then develop the best technique and apply it with discipline. Dr. Telfair was in his early 70s, quiet and unassuming, but somehow I knew I’d better watch everything he did and hang on every word, or I might miss something. I learned a lot from him.

During my college years, there was “Doc” at the big commercial lumberyard in Dayton, Ohio; a guy who just knew how to do everything better than everyone else whether it was planning out loads, backing double-axle wagons down narrow alleys, or keeping customers happy. I was his helper for two summers putting loads together before they let me go on my own, and all I ever had to think was “What would Doc do?” and I’d have the answer. You might assume there’s little art or science to assembling a truckload of lumber and accompanying materials with 20 or more types and sizes, but then you didn’t know Doc. A true “process guy”—though the term was foreign to me as a college sophomore—I later realized Doc was as good at process as they come.

Then there was Walt at U.S. Steel—my first job out of college. He had a division-level position that brought some status and a good income, but it wasn’t what he wanted. Walt wanted to run the place. He worked hard to earn an MBA a couple of decades before it became a popular thing to do and knew our end of the mill inside and out, but what he did best was to negotiate with the union. He was an incredible listener and had a way of letting the union reps know that Walt wasn’t on anyone’s side, he just wanted to work toward a mutually beneficial solution to whatever problem came along. Ironically, this very skill, which no doubt saved the company millions over the years, was Walt’s downfall in terms of promotion. He just wasn’t enough of a “hard ass” for senior management and refused to join the good-old-boy chest-pounders whose favorite pastime was denigrating the workers. Walt was near retirement and I sought out opportunities for us to spend time together so he could pass on his learning from 40 years at the mill. I often think of him.

Fast forward about 10 years to my tenure with the national builder where I had many great mentors. The older gray-hairs in their 60s, such as Doug Campbell and Bill Pulte, really stand out, and their names, like all of those mentioned above, have turned up in my columns over almost two decades. Others such as Gary Grant and Mike Rhodes were perhaps only 10 years or so older than me, but I held them in the same high esteem. I hung on every word they said. I even took notes. These were guys who had gone before and learned the lessons. It was my job to take it all in and figure out how to apply it.

Have I Lost the Plot?

That’s hardly a complete list, and it makes me wonder: Is it the same today? Are the younger ones out there, those in their 20s and 30s, still willing to learn from those who have been around a bit longer? I’ve gone back and forth on this and have spent a lot of time pondering those presentations I do that really seem to hit a nerve; the ones where you can just tell everyone is listening and engaged. On the other hand, there are those times when it seems the group is getting restless and I’d better move on before they do. What accounts for the difference? Some say it’s a new world—the Millennials are truly different. Just recently I learned of a Microsoft study that shows the average attention span of young adults has dropped by 50 percent in the past decade. But how does this jibe with the new phenomenon of “binge-watching” an entire season of a show in a single night?

Raised on Sesame Street, Millennials just don’t have the attention span for long-form storytelling. You almost never find a TV episode today that simply focuses on one storyline and develops it deeply. Programs typically have two, three, or even four plots and subplots. That’s a huge change from the past when an entire hour-long episode was based on a single storyline. In New Zealand, when someone strays from the plan or just doesn’t understand, people say, “He’s lost the plot!” But is it your understanding that’s really the problem, or has a plot developed that makes no sense? Their pronouncement that you are confused could actually be your learned refusal to accept a lousy plan.

Beyond the List

The sociographic changes in younger generations may explain the seemingly insatiable desire for “the list”—the 10 best ways to do this or that, or the 8 things you must avoid, the 13 essential foods for good health, etc. “Just read the will!” Get it done. And maybe that is a test. Is it the actual list you want or do you want to know what’s behind it, where it came from, how it was developed?

A perfect example is a builder’s start package, the plans and complete documentation that tell suppliers and trades absolutely everything that goes into a particular house. I can tell you over and over that you need it, you must have it, you have no other option. Got it? Or, I can tell you about Ryan, the superintendent who is constantly forced to start homes with incomplete start packages. Then we can talk about all of the problems and issues that he will run into, the things that trash the schedule, waste time for suppliers and trades, mess with quality, and upset customers. Which approach works for you? The first is faster, for sure. Yet my experience says that if you understand the problem from your own history, you will remember it and actually strive to improve the process. What else matters?

Battle Scars

Does having the years and the scars and the gray hair help with that? All five of our key TrueNorth associates have those qualifications in spades. My wife and I had a long discussion about it and she offered some helpful insight. She suggests that if any of our knowledge is positioned as the “old used to be”—the way we did it way back when, with the implication that “by the way, kids, the old ways were much better than how you’re doing it today”—then we lose the group. No one wants to hear about how good it was 30 years ago, even if we sport hats proclaiming, “Make Home Building Great Again!” But if we position it as, “This is what we directly observe that works, and what does not work, based on the more than 200 builders we’ve been involved with,” then you just might open up to it.

The reality is that someone at age 30 or even 35 could take the summaries and slides of the things we’ve uncovered from those 200 builders and, using great presentation skills, lay it all out there. Would you believe him or her? Not so much, I think. Who did she work for? Did she ever manage anyone? Did she have to fire people? Did she ever have to make a payroll? Legitimate questions. Our guys, all of us in our 60s, do bring a certain “face credibility” because folks rightly assume we’ve each been through those trials. But my wife and business adviser is correct: The knowledge we bring has to be a compendium of the current—what works today—not something from 30 years ago.

When I think back about my various mentors and what they all had in common—besides their gray hair and battle scars—the answer comes easily: I describe each one as a life-long learner. Ultimately, that’s what attracted me to all of them. Each knew so much, yet was continually striving to learn more and to find a better way, to improve even a good process. And each was always eager to share. Any willing student was welcome, but Lord help those who showed up just looking for a quick-fix solution. For those they showed little patience.

So now I join the ranks of my four other TrueNorth colleagues who previously attained the age of 64. The words of McCartney’s song have no doubt always sounded as trivial to you as they have to me—until you hear it just short of your 64th birthday. That song, as light as it sounds, is really a lament and expression of fear. Will you still need me? What couple or what author, doesn’t occasionally ponder that question? Will you still feed me? To the couple that speaks to the question: Will you take care of me no matter what comes? To the author: Will anyone still want to pay me? And of course, Will you still read me? I still get a lot of email responses and requests for copies of my columns and article collections, so my plan is to hang in there and keep writing as long as you consider me relevant. Each year I get to know another 15 to 20 builders, and in every single case I see something I’ve never seen before—small improvements, spectacular successes, and lousy failures. I will thus continue writing and presenting what we observe works and what does not, and stay in learning mode. I’m often accused of bringing up issues that no one else does or will, but I hope to avoid those that no one cares about. So if there is something you would like me to tackle, as McCartney sang, “Send me a postcard, drop me a line, stating point of view.” I’ll get right on it.