With one slight change to his floor plan schematic, architect Ryan White increased the production of a new single-family project by 33%.

How? By shaving just a foot off the depth of the three-story, side-by-side duplex destined for an infill lot in Pittsburgh, he enabled Structural Modular Innovations to build three boxes at a time on its factory floor instead of only two.

“Understanding the capabilities of the factory allowed us to meet the attainability goals for the project,” says White, director of design at Dahlin Group, in Irvine, Calif. “And losing that 1 foot didn’t affect the livability or marketability of the homes at all.”

As more home builders look to alternative production solutions such as modular and full-scale panelization to combat a chronic skilled labor shortage, volatile structural materials prices, and an increase in the overall cost to build, the level of design detail and collaboration with providers for new homes is paramount in achieving the benefits of industrialized construction.

RELATED

- 2023 Housing Giants Report: Holding Back the Headwinds

- 2023 Housing Giants List: Ranking the Biggest U.S. Builders

- Volumetric Building Companies' Vaughan Buckley on Restarting a Former Katerra Factory

“Design casts the biggest shadow in the whole process,” says Sara Logan, AIA, VP of design and Volumetric Building Companies, a vertically integrated modular provider based in Philadelphia. “When you look at a building as a product instead of a project, you realize that what you spend on design [typically 2% to 5% of the overall budget] has significant implications on bigger costs, such as materials [50%] and labor [15%].”

And while most builders ironically refer to their homes as “products,” considering their actual construction as a manufacturing process would be a mind shift for most of them and their design teams ... but one that needs to take place if home builders want to successfully transition from on-site stick-building to an off-site or factory-built model for the bulk of their structural needs.

Design for Construction—in a Factory

True or not, a common trope holds that architects and designers think about the look, feel, and use of their buildings more than considering how those buildings will actually get built.

That may be OK-ish with a traditional stick-built production home, where construction documents are commonly open to a certain amount of interpretation and making changes in the field isn’t uncommon. Not so in a factory.

“Before we submit anything to the building department, we know how the house is going to be built,” says Donald Carpenter, VP of product development at Oakwood Homes, in Denver, which incorporated panelization 20 years ago. “It’s about embracing manufacturing principles that everything has to be decided and designed beforehand.”

Oakwood’s long history with off-site framing, well before the company’s purchase in 2017 by Clayton Properties Group (#10 in our 2023 Housing Giants rankings), means its in-house design team is trained and geared to follow that protocol. “Our CAD [computer-aided design] modelers and drafters have become experts in how to build a house,” Carpenter says. “We’re building it as we draw it, which is a departure from the norm.”

For The Cove, a new community of for-sale detached and attached homes in Sacramento, Calif., Beazer Homes partnered with Entekra, a panelized systems provider in Modesto, Calif., to deliver about 100 homes a year that currently sell from the high-$400,000s to the mid-$600,000s. (Editor’s note: Entekra recently announced it will cease operations as of June 30.)

RELATED

- Off-Site Construction: A Real-World Study

- On-Site vs. Off-Site: a Total Cost Analysis for Home Builders

- Housing, Industrialized: Marketing to Consumers

- Off-Site Construction Drivers and Enablers—The Great Convergence, Part 2

The partnership was enlightening and impactful for the nation’s 21st-largest builder. “Everything has to be in the same place every time,” says Ray Ferrarini, VP of operations for Beazer Homes, and not just the framing components but also the plumbing, electrical, and anything else inside the slab. “That way, we’re not having to cut into panels to make something fit.”

That level of precision enabled Beazer to significantly reduce its use of framing lumber and to build faster and safer with fewer workers, among other benefits. “If we were stick-building this community, it would be a lumberyard out here,” Ferrarini says. “Now we see maybe four or five boards left over after the house is framed.”

In large part, that’s a testament to the ever-advancing technical wizardry of various computer design and modeling software programs that not only build a house and all of its elements virtually, but provide the factory and the field with precise documents and detailed spec lists that take the guesswork (and rework) out of the equation.

“We’re able to walk these houses virtually, and not just a framed house, but with all of the MEP [mechanical, electrical, and plumbing] in place,” Carpenter says. “One of our absolutes is we don’t make field decisions, so everything has to be thought out. And if it does happen, it’s brought back to the product development team [to refine the drawings].”

Gerard McCaughey, Entekra’s former CEO and chairman, puts it more bluntly: “It’s 10,000 times cheaper to fix something on a computer screen than it is to fix it on the jobsite,” and thus far, more likely to achieve the cost and time reductions and boosts in productivity and profitability that off-site building promises.

Off-Site Construction: Design for Design

While there’s a persistent notion among builders that off-site construction can’t match the design flexibility of stick-built homes, it’s a perception those with experience in the factory-built realm are quick to dispel. “There are many projects I’ve completed where you would never know they’ve come out of a factory,” says Paul Gilbert, president of E. Gilbert & Sons, in Denver, a builder, general contractor, and construction manager who often connects building owners and architects with modular providers.

And let’s be honest: The vast majority of today’s site-built production homes are designed to appeal to the masses and to reduce costs, resulting in relatively few (and usually low-cost) variations in their overall aesthetic—something panelization and modular both can match.

RELATED

“When you really look at production homes priced at three-quarters of a million dollars, they still have the same basic elements as something priced at a half million or a quarter million, right?” says Jordyn Croom, director of finance and operations at On2 Homes, a recent offshoot of Oakwood Homes focused on delivering attainable, detached starter housing in Denver. “The idea that you need to have this extreme amount of design flexibility and that off-site takes away from some of the ‘coolness’ of the house is kind of comical.”

“The possibilities with off-site are almost endless,” adds Ryan Bish, founding partner and general manager at Structural Modular Innovations, in Strattanville, Pa., near Pittsburgh. “You just have to understand the constraints of the manufacturing process, such as allowable heights, width and length dimensions, and load paths, and embrace them instead of allowing them to be stumbling blocks.”

While the term “constraints” may reinforce the stigma of off-site design’s inflexibility in a stick-builder’s mind, architect Stuart Emmons, principal at Emmons Design, in Astoria, Ore., who has designed literally hundreds of modularly built homes, points out that “every house has limited design flexibility to some extent,” such as lot sizes and shapes, setbacks, and roof heights, among other factors. He adds, “There are many architects who have designed beautiful homes with the fairly reasonable restraints of a modular factory.”

And while a given modular facility may not be set up to accommodate all product types, it certainly is for most of them, says Doug Van Lerberghe, director of strategic ventures at Kephart, a multidisciplinary design firm in Denver. “You can do a custom project with modular,” he adds, albeit at the literal expense of the economies of scale that a repeatable design and build affords in a factory setting.

To at least combat the design flexibility myth, Van Lerberghe has toyed with applying exterior finishes on site instead of in the factory to “make it look less modular” upon delivery, while Emmons suggests details such as cathedral ceilings may be easier to build in the field than in a factory.

For the duplex project in Pittsburgh, however, White and Bish are collaborating on the finer details of the homes’ exterior cladding and trim package, but not whether to apply those finishes on site. “It’s more about what the materials are and how they’re applied in the factory, so that when the homes are delivered, they’re ready to go,” White says.

Industrialized Construction Road Map: In 2020, with the help of a working group consisting of home builders, suppliers, researchers, and other industry experts, Pro Builder and Pittsburgh-based Housing Innovation Alliance initiated the development of a comprehensive “Industrialized Construction Road Map” to outline a successful transition of a builder’s overall business model—not just the construction silo—to fully integrate IC into its operations and realize the benefits. This article is one within a series produced to that end, and both Pro Builder and the Alliance maintain stores of research reports, webinar recordings, meeting notes, articles, and other resources for builders.

Design for Affordability

While the design flexibility debate rages on, the bigger question is whether a jaw-dropping front elevation is necessary or truly valued by a growing contingent of buyers unable to afford a new home. “When we’re talking about people who don’t have many housing options, the goal is no longer something that makes you go ‘Wow!’” Croom says, “the goal is a home. And in our industry, it’s sometimes easy to lose sight of that.”

To stay focused on its goals for attainable housing, the On2 team simplified floor plans, elevations, and options while keeping an eye on marketability through a series of focus groups with first-time buyers. “We got all of this information, analyzed it, and came up with something that frankly would work really well if it was site-built,” Croom says, “but we then took it a step further by building it in a production environment that would ensure we could build it through drywall in five days.”

That step reduced cycle times enough to keep first-time buyers qualified for a mortgage—a new wrinkle given recent and multiple interest rate hikes.

It was a similar tack Carpenter took at Oakwood when On2’s mother ship decided to invest in attainable housing for its own product line, too. In addition to looking inward at its products, processes, and production to lower costs and deliver faster, Carpenter and his team toured a few dozen of the best-selling affordable housing communities in the country to glean their secret sauce.

“It’s OK to figure out what’s best built in the factory and what’s best to build on site to achieve your goals. I think if builders understood that, they’d be more willing to embrace it.” —Eric Schaefer, chief business development officer, Fading West Development

Turns out it was simplicity, in both style and construction. “We expected to find some unique, cutting-edge type of products, but there was none of that. It was very traditional,” he says.

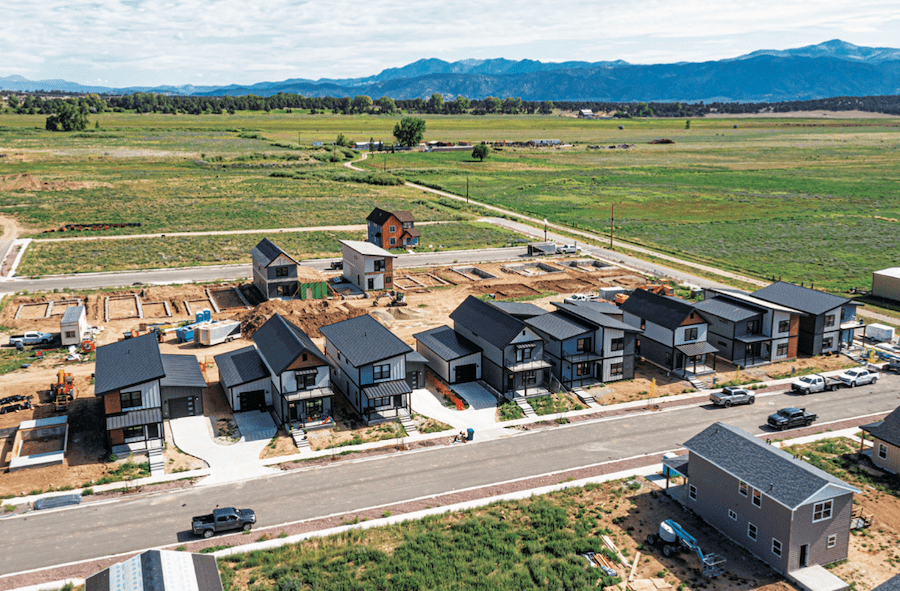

Fading West Development, a vertically integrated modular builder and community developer based in Buena Vista, Colo., takes the concept even further in its efforts to provide affordable workforce housing for municipalities and private employers of mainly service workers, such as resorts.

“We force our clients to use our standard box sizes and finish packages to achieve affordability for a teacher or a firefighter,” says Eric Schaefer, the builder’s chief business development officer. “There are no other options.”

Even so, mixing and matching 16-foot-wide by 50-, 38-, and 26-foot-deep modules (not to mention an accessory dwelling unit box) offers a marketable measure of design flexibility, and Schaefer does not discount the opportunity to site- or locally build some of the homes’ structure—roof trusses, for instance—if it makes better financial and cycle-time sense. “It’s OK to figure out what’s best built in the factory and what’s best to build on site to achieve your goals,” he says. “I think if builders understood that, they’d be more willing to embrace it.”

Already in the know, Beazer’s Ray Ferrarini is a convert. “I think a lot of builders are going to look at this process and say, ‘You know what? It’s worth it. We’re going to get a better product, we’re going to get it faster, and it’s going to be less risk for us,’” he says. “That’s why I’m a big believer.”

BotBuilt: Turning the Off-Site Design Debate on Its Head

If you think an operation that uses robots to assemble framing components would require the most sophisticated level of construction documentation imaginable, not to mention capital investments in the hundreds of millions, think again. In fact, it’s just the opposite.

BotBuilt, a recent entrant in the off-site game, buys used robot arms from the auto industry on eBay, applies proprietary software to interpret just about any plan you can throw at it—regardless of detail or complexity—and churns out a complete panelized package from its Durham, N.C., facility in a fraction of the time and at a fraction of the cost of an on-site build, even compared with other panelizers and modular shops. “Some of the plan sets we get are hot garbage, but we can work with it,” says CEO Brent Wadas.

The ability to build from any set of plans in any format, he says, is the key to changing attitudes about off-site construction. “Forcing an industry to change the way it prepares and submits documents is a losing battle,” according to Wadas. “We say, let builders be builders and we’ll be the nerds in the room.”

Also against conventional off-site wisdom, BotBuilt targeted custom homes right out of the gate. “In truth, we just wanted to take on the hardest projects first,” Wadas says, after which everything else is relatively easy for the software and the bots to build ... at about $2 per square foot, regardless of sophistication—far less than any other framing solution. “If you can’t do this cost-effectively at scale, you’re going to run into problems when the market slows.”