City living is cool again. Demand for infill housing is growing as aging baby boomers join yuppies in line for homes that have one thing in common: a location in the heart of town, close to jobs, entertainment and shopping. But where do you find the land for such new urban neighborhoods?

Buying up an existing block or two, and tearing down the old houses happens a lot these days. Fortunately, there’s another option. Many cities have underutilized or obsolete buildings and old industrial sites located in close proximity to desirable commercial, shopping and entertainment districts. The only hang-up is that these sites are usually "brownfields," requiring some level of environmental cleanup (although usually not removal of toxic waste).

Most home builders run for cover at the thought of trying anything so risky and so far from their comfort zone.

But there are now reasons to take a closer look at brownfields redevelopment. Besides the burgeoning demand ratcheting up the underlying value of these sites, there’s the political pressure on local and state governments to clean them up and remove "blight" from the urban landscape. In the age of "smart growth," there’s a white hat and a shiny new good-guy image just waiting for builders willing to partner with local governments in such cleanups. That’s quite a contrast from what often waits for you at city hall if you stick with traditional suburban residential development.

Moreover, recent advances in the diagnosis of sites and the technology of environmental cleanup have dramatically reduced the risk and uncertainty of brownfields redevelopment. All of this pushed us to another important milestone, the emergence of new insurance products to make the sweaty palms and heart palpitations associated with brownfields a thing of the past.

"Local and regional governments have really seen the light, and are committed to helping speed the approval process for restoration and repositioning of lightly contaminated sites," says Los Angeles lawyer Timi Hallem, a specialist in land use and brownfields redevelopment.

"There are 450,000 abandoned brownfields throughout the U.S.," says Hallem. "Whether these sites are in urban or outlying areas, they represent enormous opportunities for both the developers who breathe new life into them and the cities that benefit from them."

Two new types of insurance reduce the risks of brownfields redevelopment, says Hallem. "The first is what’s called ‘stop loss.’ It insures against the cost of clean-up exceeding some predetermined threshold. There’s a deductible, but if your costs exceed budget by more than that, the insurance kicks in.

"The second is a specialized form of liability insurance, which covers against your own or third-party claims of damage resulting from unforeseen environmental conditions. It covers all additional costs, including interest carry and renegotiating contracts or sales, if an environmental problem is discovered on a property after it’s been cleaned up."

It would cover the builder against a third party emerging at a later date and claiming that the pollution that used to exist on the site harmed his or her health or well being, Hallem reports.

"Because of all these developments, it’s now possible to make a reasonable determination, up front, about the potential profitability of a site. You know what your costs will be, and have a pretty good idea how much value can be realized from the proposed development."

Oil Country Cleanup

What kind of successes can be achieved in brownfields redevelopment?

Spectacular in many cases. Hallem represented Catellus Development in the purchase of an active oil refinery in Hercules, Calif., that happened to occupy 206 acres of a bluff overlooking San Pablo Bay, 25 miles from downtown San Francisco. Views from the property stretch for miles toward Marin County.

After decommissioning and dismantling the refinery and tank farm, Catellus is now finishing up remediation of soils and ground water on the site.

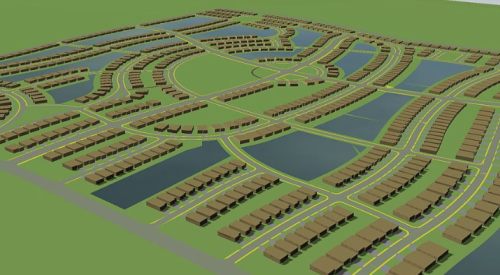

"We’ve now completed all of the land-use entitlements," says Catellus Residential Group president Tim Unger. "We will develop about 850 lots on the site for mostly single-family homes, in eight to ten product types, ranging in price from $200,000 to nearly $500,000."

The masterplanned community, all built on top of the old refinery site, will also include a six-acre retail component and a site for an elementary school.

"We’ve actually sold the first two residential parcels to a local builder," says Unger. (Catellus sold its own home building division to Brookfield Homes eight months ago.)

Unger says he marveled at the intrinsic value of the property when he first visited the refinery several years ago. "I looked at those views and said,’Man, if we can get rid of this refinery, this could be one of the greatest residential land buys in the history of the (San Francisco) Bay area.’

"Eventually, we acquired the site. We had to go through some pretty exotic LLC entities and take out a lot of elaborate insurance coverages. We also had to negotiate cleanup standards with the regional water quality control board prior to closing escrow.

"It’s a fascinating study in the creation of value," he says. "We sank a lot of money into the site, but we got it for a bargain price. And the financial results are still very attractive. We sold the first two residential pods for more money than we have invested in the whole site."

Still, even with all of that, Catellus filed a claim with its insurance carrier on its stop-loss policy. "We exceeded our self-insured limit on those costs," says Unger, "mostly because of the way we had to grade the areas of the site that were contaminated. It was fairly minor, and that was the only surprise, but I’m still glad we had the insurance policy."

One of the best things about the site was its neighbors. Single-family houses backed up against the refinery.

"From the very beginning, there was no opposition to this development," says Timi Hallem. "It’s amazing how attractive residential development becomes when the existing land use is an oil refinery."

That’s something to think about on the way to your next planning board meeting or zoning hearing.