|

In Lancaster County, Pa., an hour's drive west of Philadelphia and bristling with suburban expansion, builders, regulators and the general public are recognizing that growth is inevitable and sensible planning is needed to address it.

For decades the county sought to foster a local version of smart growth. In recent years, as national and local builders have met market demand under existing ordinances, few have had the resources or the will to undertake major zoning revisions. But East Hempfield Township, with 21 square miles and a population of 22,000 and growing, was different than most.

"For years we'd been looking at how to do things a little bit differently," says George R. Marcinko, township manager. He disliked "cookie-cutter developments," yet sought to "maximize growth while retaining the local character."

Lancaster-based Charter Homes recently put that claim to the test when it worked with the township to rewrite the book on zoning while also creating a new kind of land plan. The result: Veranda, a unique community with an equally unique development story. To be able to tell Veranda's story, however, the builder would have to rescue 62.8 acres of open space from a sort of regulatory "Twilight Zone."

Out of the zoneWhen East Hempfield Township enacted its last comprehensive plan in 1994, the land for this project was designated "Agricultural Holdings." According to Marcinko, this unzoned classification denotes "land that was agricultural in use, but was expected to be developed at some point in the future. We didn't want to set down the type of development until we knew what we would need." Marcinko says that the township expected it to take 10 years for the right development opportunity to surface. That prediction was right on target.

Unlike a typically zoned parcel that a builder can develop under an existing ordinance, this particular parcel carried no automatic right to build. Instead, a builder would have to submit to a full entitlement/approval process from scratch, even if applying conventional ordinances used elsewhere in the township. Charter Homes had control of the land for Veranda through options and contingencies, and Rob Bowman, company president, took the zoning challenge as an opportunity to make a bold land-planning statement.

The land's intrinsic valueBowman says each piece of land has a story to tell and it's the developer's job to bring that out in the land plan. "Instead of asking, 'How many homes can we get on this land?' and working backwards, we asked 'What belongs here?' and set out to determine the context for a new neighborhood," he says. "The first step was to start by valuing everything that creates a sense of place."

The parcel bordered Harrisburg Pike and held a corridor of streams as well as several disconnected pieces of a trail system that would later be connected to form a natural amenity. This context, or "story," provided an opportunity to define the shape of the community to come.

This project wouldn't be ruled solely by the spreadsheet. "The land has an intrinsic value beyond dollars and cents," Bowman says, stressing the need to preserve the local values embedded in that rural soil. He adds that residents, including himself and Charter Homes employees, carry a "personal connection to and a stewardship responsibility" for the land.

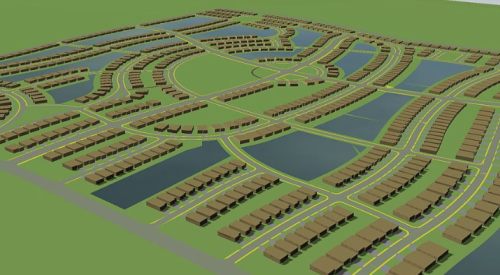

Making the pitchCharter previously rewrote the rules of development elsewhere in Lancaster County with Millcreek, a project with modified zoning and land use rules. Millcreek won awards ranging from local smart growth kudos to the Best in American Living Award. Millcreek's plan put 237 homes on 84.7 acres (gross, pre-development), leaving 33 acres for open space. Veranda similarly puts 183 homes on 62.8 acres in East Hempfield and leaves a little more than 17 acres of those acres open.

Marcinko admits Millcreek impressed township supervisors to "work with the idea" for Veranda because he and his supervisors knew that this type of development was "something that we need to be looking at."

Bowman tapped Jim Constantine of Looney Ricks Kiss, a design, planning and research firm based in Princeton, N.J., to create a master plan, work with the planning board and its public policy objectives and replace the land's unzoned status with a new plan that would get the project go-ahead.

"The land was in 'ag holdings,' so we knew the town was looking for a better way to do things," says Constantine. "But there was no vision for what it should be. Rob came to us and said, 'Create that vision; be bold, take a look up and down this whole corridor and let's help these people get what they want. Let's be a good neighbor.'"

Constantine created the first design iteration as a "soft" vision to illustrate the general size, shape and open space characteristics Veranda would possess. The general plan was superimposed over an aerial view to show the project in its context, and stress that this wasn't an isolated project. The plan was included in a presentation at the first and only official public meeting on Veranda in July, 2002 following months of informal meetings with area residents.

Coming off the meeting, Constantine says two things became apparent. "There will always be some people who prefer that the farm next to their community remain open and undeveloped." But he added that many at the meeting voiced approval, indicating, "If anyone is going to develop this property, I want it to be my builder, Rob Bowman." Many of these voices came from residents from the Sylvan Crossing community adjacent to Veranda, also built by Charter Homes. The builder's advance outreach provided critical goodwill.

What Charter ChangedWith area housing in 2003 ranging from $130,000 to $1 million-plus, Bowman wanted to make money, but he dismissed one possibility of a conventional one-acre subdivision-style neighborhood of 37 high-end homes. "That would have been a lot easier to do and with a lot less risk," he says, but wouldn't meet his desire for a more diverse buyer base and creation of a "sense of place."

Another existing ordinance, however, had something to offer. Ordinance "R-2" had financial and aesthetic shortcomings but would serve as the basis for an overlay of revisions to come. Conventionally applied, the ordinance would accommodate up to five homes per acre. However, actual density was often reduced to as few as two units per acre because of sometimes-contradictory rules, the builder reports.

Charter won its approval in two stages. The company petitioned for rezoning from agricultural holdings to R-2 in February 2002, winning approval in July following the public meeting. That set the stage for Bowman and Constantine to push for a full set of standards for street geometry, lot sizes, setbacks and more in the form of an overlay of changes to R-2 that would fulfill the vision of creating a profitable, attractive, pedestrian friendly and environmentally sensitive project. The following list highlights a few of the changes that were submitted:

- Traffic calming through the allowance of narrower streets (20, 24 and 28 feet wide) with tighter curve radii and shorter tangents (for closer left/right turns) as well a speed bump-like platforms in the road that double as raised pedestrian walkways.

- Smaller lots with narrower frontages. For instance, single-family home lots range from 6,000 to 10,000 square feet.

- Shorter setbacks in front and on the side of the house of 10- and five feet, respectively.

- The use of alleys (14 feet wide) and rear-loaded garages.

- Clustered lots for higher yield on developed areas, more pocket parks and other open-space amenities throughout the plan.

- Higher lot coverage ratios and a related increase in impervious cover to between 65–70% while infiltrating back to the ground all storm water up to a two-year storm standard. (Beyond that, groundwater recharge/detention is handled via detention basin and swales.)

- A greater mix of attached and detached product, which can coexist on the same street. Townhouses can be built directly across the street from single-family homes for greater neighborhood diversity.

- Landscape and hardscape enhancements, including pocket parks to a requirement to provide a greater variety in the size and type of trees to avoid a cookie-cutter landscape appearance. Granite curbs grace the hardscape.

Charter petitioned for these changes as part of the full overlay in September 2002 and won approval in January 2003. The result was two ordinances: a Neighborhood Design Option that gave the builder — and by extension others in the township building under R-2 — the by-right option to use the overlay standards; and a Neighborhood Design Standard detailing the standards.

Marcinko says Charter presented its case "with good arguments for the benefits of each detail, and they engaged us in a healthy give and take. The community gave up some things they were concerned with and Bowman gave up some things with which he had concerns. That's the only way to make things work. It's the only way to create a good relationship between local government and the developer."

There were a few impasses, but Bowman respected concerns from parties such as East Hempfield's volunteer firefighters who were concerned about the narrower streets. The builder compromised with restricting parking on those roadways, and in return, believes township supervisors allowed him to "drop some streets down to a width that, frankly, I don't think they were all comfortable with. But they allowed us to do that as an experiment — to see if it works or not."

Marcinko says "the verdict is still out" on that particular issue but he's glad to see it tested. "There was a healthy give and take," he adds. "That's the only way to make things work — by having a good relationship between local government and the developer."

The new ordinances helped a township update zoning rules that remained largely unchanged for 40 or more years as changing consumer demand and community development issues kept evolving. The builder's partnership with East Hempfield also helped preserve more open space than traditional development while creating the proverbial "sense of place" all parties sought to create — and preserve.

Early indications of successVeranda represents a win for Charter Homes and builders who follow in the company's footsteps. The company and East Hempfield Township were given a smart-growth award by Lancaster County Commissioners and the county's Planning Commission.

Of course, another kind of win is needed for the builder to thrive in its mission: The community has to be profitable. Bowman would not disclose financial details but the company pre-sold 39 homes before opening its first model in March of this year and is likely to see additional benefits through reduced roadway and infrastructure costs and more economical storm water management and compliance.

Such benefits are detailed in a report, "Recommended Model Development Principles," released in March by the Lancaster County Area Site Planning Roundtable, with which George Marcinko and Charter Homes hold seats. Veranda's plan is consistent with much of the report, giving reason to believe the project will benefit the township with increased storm water compliance as well as new property taxes, while buyers will benefit from more green-space, safer roads and higher property values.

"Our entire philosophy is based on the fact that whether people want to recognize it or not, development will occur," says Bowman. "The question is: What kind of places do we build? The answer, too often, is that we'll approve 55 and older neighborhoods because they're less of a tax burden. But that doesn't address where we'll put the rest of the population." He says a builders and municipal planners must work together to address a broad product mix.

He also advises preservation of natural surroundings as good business as well as good politics. "The conversation over development versus no development needs to move another step toward preserve those very assets of the places where we live, the values we want to perpetuate. There's a much richer conversation to be had, there's much more at stake and there's a huge opportunity to start thinking about these things — and doing something about it.

|