|

Controversy has brewed ever since the landmark 1926 U.S. Supreme Court decision of Village of Euclid , Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co., which established the separation of land uses among other restrictions to manage nuisances and protect the public welfare. The resulting "Euclidian" form of zoning has long since been accepted as the standard for regulating development nationwide. However it has come under attack as an inadequate tool for dealing with today's seemingly endless growth management conflicts.

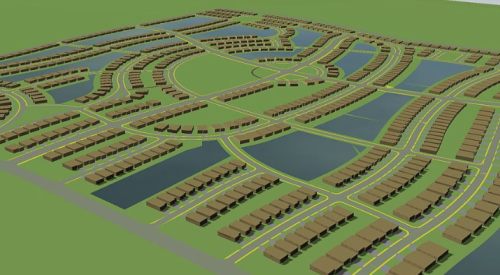

Critics of conventional zoning believe the time has passed for strictly promoting the segregation of residential, office, retail, civic and other land uses separated by pedestrian-unfriendly roadways and poorly designed open-space buffers. They claim that this degrades social interaction, quality of life and the natural environment. They say developers should be allowed to create compact, walkable, and diverse mixed-use communities, and that these can benefit both the community and the developer's and builder's bottom line.

Has conventional zoning outlived its usefulness? Proponents of "form-based codes" say yes.

Euclid's UndoingConsidering the changes of the past 80 years and current demands for smart (or at least smarter) growth, it's possible that all of the regulatory tools and tweaks have only complicated matters. These tools and tweaks include conditional use permits, overlay districts, planned unit developments, design guidelines, performance zoning, variances and tax/density bonuses. In contrast, form-based codes are revolutionary; they seek to replace the entire system by streamlining ordinances and shifting away from land use and density as primary regulating factors.

Compared to conventional zoning practice, form-based thinking is not a simple sell to regulators. "It's a whole different approach; you can't just take your zoning and rewrite it into form-based code," says Peter Katz, New Urbanist consultant, professor in practice at Virginia Polytechnic State University and president of the Form-Based-Codes Institute.

One extreme example of regulators' difficulty with change occurred in planning the Cornell community, a 5000-acre plan for an unused airport site outside of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, designed by Miami-based Duany Plater-Zyberk & Co. (DPZ). Here, local plans were subject to approval at the provincial level. "At great expense," Katz says, "the province hired several local planners to re-write DPZ's diagram-rich form-based code into a nearly all-text document."

In the United States, however, the typical local jurisdiction has the legal flexibility to accommodate form-based ordinances. Last July, for example, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed into law Assembly Bill 1268, which established form-based coding as a legal option for cities to include in their general planning and zoning processes. This followed successful early adoptions by jurisdictions including Petaluma, and the city of Hercules, a fast-growing San Francisco area bedroom community of 23,000.

Under conventional zoning, Stephen Lawton, Hercules' community development director, lacked the design toolkit for traditional neighborhood design and found that "form codes can do that."

Since the 2001 approval of a new form-based code's Regulating Plan drafted by urban design firm Dover, Kohl and Partners, based in Coral Gables, Fla., redevelopment has transformed the 400-acre site of a former dynamite plant. So far, 500 single-family houses have been completed and townhouses with live/work units are on the way. Four builders are involved: DR Horton's Western Pacific Housing unit, William Lyon Homes, John Laing Homes and Taylor-Woodrow homes.

Lawton believes that "form[-based] codes will take over the next generation of planning in California" and affect all developers and builders because they are "increasingly going to have to deal in an environment where municipalities are using form codes to regulate production housing." This, in turn, will affect where and how lots will be available, and who wins approvals. "To the extent that home builders attempt to pass this off as a fad or as a fashion," he adds, "they are not going to be viewed favorably by the municipalities, and it's going to be more expensive to get their projects done."

Streamlined OrdinanceForm-based codes reinforce the notion that a picture is worth a thousand words by putting most of a plan's key dictates into diagrams. Ordinances can be just a few pages for a development that would need dozens of pages in conventional zoning documents. There are only a handful of components in a form-based ordinance:

- Regulating plan: Maps what goes where — every street, block and building type, or mix of types; defines property lines, required building lines (similar to setbacks) and public spaces — in more detail than conventional zoning maps.

- Building form standards: Establishes four parameters in cross-sectional drawings, typically on one sheet for each building type: 1) Height: Maximum number of floors; also minimum needed for a proper street wall; 2) Siting: Placement of structures in relation to streets and adjacent lots; front, side and rear building limits; and specs for entrances, parking and yards; 3) Elements: Dimensions for windows, doors, porches, balconies, stoops and so on; 4) Uses: Configuration of specific uses within each building type. Note: Use is not ignored, but dealt with at this secondary level.

- Thoroughfare standards: Included if streets are not individually designed. Diagrams can define dimensions from travel and parking lanes through sidewalks, medians and planting strips.

- Landscape standards: Lists accepted tree and groundcover species and location details.

- Definitions: The glossary helps clarify specific terms.

- Architectural standards: Optional based on community and developer desire for regulatory controls. May dictate materials and finishes, colors or other controls.

Form-based plans do not stand alone, explains Katz, but are usually embedded in a set of best practices that includes three elements: "a compelling urban design that citizens can get excited about; a public process that gives them a sense of ownership of the plan; and the ordinance itself. They're like three legs of a stool; without one of the legs, it falls down."

Public and Private Sectors WinFor developers and builders, there are pros and cons to working within a form-based regulatory environment. The great deal of detail required in up-front planning may be daunting, even constraining by their fundamentally different nature.

Conventional zoning is proscriptive: it defines what is prohibited rather than what is desired. But by focusing on what builders can't build, critics say, it does not predict with any certainty the appearance of what can or will be built — and invites conflict. In contrast, form-based codes are prescriptive: they define building types, streets and the public realm down to the block-level, whereas conventional zoning stops at the subdivision level and therefore cannot cope with the details of mixed use, varied thoroughfares and so many other factors.

By releasing conventional restrictions on land use and density, many community developers and builders may find greater flexibility to create plans with higher density. Additionally, they may find it easier to "sell" such plans to communities because their easy-to-grasp graphics may present better than words and numbers. If so, form-based codes appear be well-suited to address growth issues such as housing affordability, transit-oriented development, pedestrian-friendly communities, open space preservation — in general, smart growth issues.

Time will tell how this new coding system fares over the established Euclidian order. But this new type of regulation may provide a clearer view of the shape of new development in the earliest stages as well as a clearer path to smarter growth and development.

|