|

The AirCycler helps a home achieve uniform temperatures from room to room by drawing and mixing air from all the rooms in the house with outside air.

|

A properly designed and installed whole-house ventilation system provides fresh air, filters and mixes the air, and then distributes that air around the house, all with minimal maintenance.

Normal, noisy bath fans don't qualify, as they're typically run such a tiny fraction of the day that the air exchange they achieve is insignificant. Most homes don't even have a kitchen exhaust fan. If homeowners don't wash out the grease traps in their recirculating range hoods, the crud trapped up there might eventually qualify as a toxic mini-dump.

"I don't think the public really knows much about ventilation and their options," says John Bower, author of Understanding Ventilation and president of the Health House Institute. "hey rely on builders, and most builders haven't offered much. Until builders talk about it, ventilation systems will remain the exception. As time goes on and ventilation evolves, people will be willing to pay more for ventilation. In recent surveys, when people are asked about healthier houses, they say they would be willing to pay between $1,000 and $2,000 for a good ventilation system."

The good news is that entry-level whole-house ventilation systems costing a fraction of that figure are being installed by a handful of large production builders today. A well-thought-out system provides their buyers with better quality air, and the builders garner a sales edge and some liability protection.

Changing Current Practice

Mark LaLiberte, building science trainer and materials supplier for Shelter Supply in Minneapolis, stresses an angle that seems counterintuitive. "The only way to get proper relative humidity and good indoor air quality starts with tightening up the shell," he says.

For a lot of builders, the notion of first tightening a house and then mechanically ventilating it is nothing short of nonsense. Why not just let the necessary fresh air come in through natural leakage, equip the house with a few bath fans and a small kitchen fan, and call it good?

Trouble is, natural leakage is uncontrollable and unpredictable. During some months homeowners will get too much weather-driven air exchange, and on many days they won't get any. Rarely does natural leakage "distribute" the infiltrating outdoor air evenly around the home.

Most bath fans are so noisy that they're used only to mask bathroom sounds. Typically they get turned off too soon to exhaust any significant water vapor during or after bathing.

But change is coming. Building codes in three states Washington, Minnesota and Vermont already require whole-house mechanical ventilation. And upgraded codes aren't the only driving force. A small but growing number of large production builders have made the leap to mechanical ventilation. Eventually, the mold stories all over the news will influence home buyer receptivity to paying for ventilation.

How Much Ventilation?

The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers has proposed a residential ventilation standard specifying that home ventilation systems should be sized to supply 7.5 cubic feet per minute per bedroom, plus 0.01 cfm per square foot of conditioned space. For a four-bedroom, 2,000-square-foot home, that translates to 50 cfm.

High-performance home programs such as Engineered for Life and Environments for Living have a simpler formula that gives roughly the same answer: 20 cfm for the first bedroom and 10 cfm for each additional bedroom. For the four- bedroom home, the math still calls for 50 cfm of fresh air.

Indoor air quality researchers tend to favor continuously operating systems. Field consultants lean more toward what works on a cost-effectiveness basis for their clients. In either case, the objective is to eliminate today's predominant reliance on "accidental" ventilation, replacing it with controlled ventilation.

With all three generic ventilation options described below, you still need to install a dedicated kitchen exhaust fan to exhaust odors and water vapor, plus vent any combustion gases.

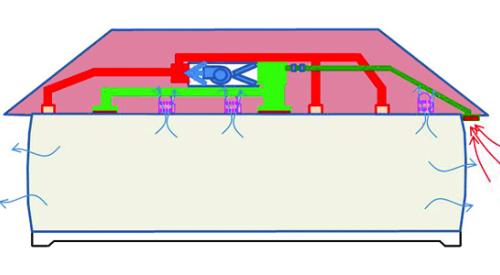

Entry-level ventilation: The central-fan-integrated approach (Figures 1 and 2) is a low-cost, whole-house ventilation option installed in production homes built to the U.S. Department of Energy's Building America standards. Fresh air is ducted typically through a 6-inch duct with two in-line dampers to the return-air side of the furnace or central air system.

|

Figure 2. Entry-level ventilation systems can be placed in the attic or the basement to draw fresh air into the return-air side of the furnace or central air system.

|

When the blower operates, it draws in a percentage of air from the outdoors; the HVAC technician presets the amount by adjusting a manual damper. The outside air mixes with the home's return air, is run through the central filter and gets distributed throughout the home via the central ductwork.

If the system's central fan hasn't operated during mild weather, a special controller the AirCycler automatically turns on the fan. According to Armin Rudd, inventor of the controller and consultant to large production builders through Building Science Corp. (Westford, Mass.), the maximum amount of outside air drawn into the system should vary with climate (see table, page 95).

Rudd says the desired run time for the ventilation system is about 10 minutes every half-hour whenever the home is occupied and windows aren't open. When the system isn't moving air, the AirCycler closes a motorized damper in the fresh-air duct. This prevents pooling of unmixed cold air within the return-air system, which might otherwise cause warranty problems with heat exchangers in furnaces.

A major comfort benefit of the system is a reduction in room-to-room temperature differences. On sunny winter days, homes with south-facing windows can develop cold zones along the north side if the thermostat hasn't called for heat. But because the AirCycler draws and mixes air from all rooms when it periodically brings in fresh air, uniform temperatures are easier to achieve.

Building America builders such as Centex, Pulte and Albuquerque, N.M.-based Artistic Homes have installed roughly 15,000 of these ventilation systems. According to LaLiberte, an HVAC dealer's cost of materials for the system is roughly $125 for the controller, a 6-inch motorized damper, plus the additional ductwork, adjustable damper, vent cap and wiring.

Once HVAC installers are familiar with the system's features, installed costs should be about $200. Some code jurisdictions allow the AirCycler system to reduce combustion-air requirements by one combustion-air duct, which offsets some of the ventilation system's costs.

|

||||||||||||||||||

Exhaust-only ventilation:

This approach uses a quiet central exhaust fan and dedicated small ducts to extract air from several rooms simultaneously. It replaces all of a home's typical bath fans, which helps reduce system costs. Mounted in a remote location such as the attic, a product such as an American Aldes or Panasonic fan can barely be heard when it's functioning.

Depending on home size, fan size and the amount of ductwork present, the fan can be set to function continuously or intermittently. Install a switch so the fan can be shut off when the building is unoccupied. During showers and bathing, the Aldes fan's airflow can be boosted for more effective ventilation of water vapor. Costs for these systems vary with features and number of small ducts; a typical range is $600 to $1,000.

One disadvantage of the exhaust-only system: The incoming "fresh air" comes from uncontrolled locations. If that air enters from a crawl space or an attached garage, it probably brings pollutants with it.

The exhaust systems also contribute a slight amount of negative pressure to the home not necessarily a good idea if the home has an atmospherically vented combustion appliance (the typical water heater). Exhaust-only systems are most appropriate when homes have detached garages, no crawl spaces, and sealed or power-vented combustion appliances.

Ventilation with energy recovery: Ventilation systems with heat recovery cost up to $2,000 installed, depending primarily on whether a dedicated complete ductwork system is required, such as in a home with hydronic heating, or whether the home's heating and cooling ductwork can provide a boost.

Heat recovery ventilators (HRVs) use a heat exchanger core to condition fresh air drawn in from the outdoors. On a cold day in Minneapolis, minus-10-degree air is warmed to about 50 degrees by air's being exhausted on alternating sides of the heat exchanger's plates.

In hotter climates such as Phoenix's, energy from cool indoor air's being exhausted can be used to cool hotter outdoor air being drawn in.

To reduce an HRV system's ductwork costs, Building Science Corp. recommends taking exhaust air from the master bedroom and supplying the fresh air into the home's central area. When the thermostat calls for heating or cooling, the centrally supplied fresh air is drawn into the home's conventional ductwork and circulated to all rooms.

During mild weather, an AirCycler controller (no duct to the outside is needed this time) runs just 10 minutes an hour to help circulate the HRV's fresh air throughout the home.

A relatively new product, the Guardian Plus by Broan-NuTone, has raised the bar for the HRV industry. Priced the same as a standard HRV, the Guardian Plus combines energy recovery ventilation with HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air) filtration. Quotes from distributors in Minneapolis and Denver indicate the Guardian Plus costs a dealer up to $600.

The typical cost of installation varies from twice to three times this amount, depending on the amount of dedicated ductwork.

Power Draw

Will running a ventilation system increase electric bills? Compared with most homes that have just heating and air conditioning systems, the increase could be $50 a year. But in some cases, they break even.

The HVAC industry often recommends that blowers be run on low speed 24/7 not a good idea in humid climates or with inefficient blowers.

A 1,000-cfm conventional blower motor consumes about 280 watts when operated at low speed and 400 watts at high speed. Installing a power-saving ECM motor cuts energy consumption by roughly 75% but adds $400 or so to the purchase price. Most builders won't go that route.

But Building Science Corp. says running a conventional blower continuously at low speed uses more energy than running the system at higher speeds 20 minutes per hour to circulate house air and bring in fresh air.

Rudd has field data indicating that the combination of a continuously operating 90-watt HRV plus 10 minutes of extra operation by the central air system blower costs roughly $75 a year. But that combination system uses less electricity than running the central blower 100% of the time at high or low speed ($310 and $240, respectively, with average heating/cooling operation).