Sometimes a builder has to play hardball.

Michael Marini had a Los Angeles infill site that was fully entitled and zoning approved. From the get-go, the CEO of Planet Home Living planned to underbuild an eight-unit, three-story project. It was fully set back, required no zoning variances, and complied in every way with the city’s small-lot ordinance. About 30 neighbors challenged the plan anyway. A municipal committee heard their appeal, sided with the neighbors, and recommended that the builder reduce the building height and add parking spaces. “We could have fought that, and half our company said we should fight it because we can’t let these things happen,” Marini says. “But we made an effort to listen and work with [the demands] even though we felt that, ultimately, we would prevail if we fought it. So we said OK, we won’t contest it, and let’s move forward.”

But then other neighbors abutting the property filed a lawsuit against the city, charging that the appeal and approval process was invalid and naming Marini’s company as a party of interest. The plaintiffs’ chief demand, among many others, was to reduce the project from eight to six units. That change wouldn’t have penciled out in terms of generating a return for Marini’s investors.

A couple of months later, Marini found himself in a conference room with the neighbors and their attorney. The plaintiffs restated their demands, and Marini told them he wasn’t going to fight them anymore for a project that already was code compliant and approved. Instead, he said he would scrap that plan and build an apartment building with 12 units of affordable housing. This complex would be bigger than his original plan and would be built to the very limit of the setbacks. Best of all, Marini would be able to break ground in short order because, unlike a small-lot ordinance project, the approval process for apartment construction doesn’t require jumping through a series of discretionary approval hoops.

The plaintiffs and attorney left the room for a short discussion. When they returned, the plaintiffs agreed to drop the lawsuit if Marini moved a window on a wall facing a neighbor’s home. And, as part of the settlement, Marini required the removal of a false, negative Yelp review that had been written by one of the plaintiffs. “We work so our first submittal is our most reasonable one,” Marini says. “It’s scaled back, we’ve done all these things that we believe are already correct, but we still get challenged, so then what are we supposed to do?”

NIMBY Attitude: A Given When It Comes to Many New-Home Developments

In some locales, zoning has little meaning. Municipalities and counties have multistep processes that provide opponents with plenty of opportunity to demand what should and shouldn’t be done with property they don’t own. Home builders of all sizes complain that in many locales residents have a sense of entitlement to stop or alter a project just because they don’t like it, citing impact on traffic, property values, safety, character of the neighborhood, or the environment. Steven Mungo, CEO of Mungo Homes, in North Charleston, S.C., had to sit through a hearing listening to opponents of one of the builder’s projects in Charleston reminisce about trekking to and picnicking under a grand oak tree on a proposed Mungo community site. “I got a kick out of the fact that they had to admit to trespassing on my property,” he says.

It’s a NIMBY (not in my backyard) world out there, but the perception that it’s overrun with tree huggers and naysayers opposed to any kind of change is an oversimplification. “Quite frankly, everyone is [guilty of being] a NIMBY,” says Sara Ellis, a former real estate lobbyist and current VP of Roni Hicks & Associates, a San Diego agency that helps developers and builders nationwide steer property through entitlement by constructively engaging with elected officials and communities. “When you own a piece of property,” she says, “it’s a large part of how you live in the world. It’s your home. Of course you’re protective. It can be scary that something could change.”

Behind any successful entitlement effort is deep and strategic research of the community and its political landscape long before a permit application is filed. The goal isn’t so much to get opponents to support your project as it is to strive for consensus by establishing trust, respecting different opinions, and forming relationships. “You have to do your homework,” says Ken Ryan, a principal with Irvine, Calif.-based KTGY Architecture + Planning, which also does consulting for building industry clients navigating various jurisdictions and local opposition. “That means understanding the total environment, from the community perspective, the decision-maker perspective, and the [municipal or county] staff perspective. You need to take the time up front, otherwise you’re going to spend it on the back end.”

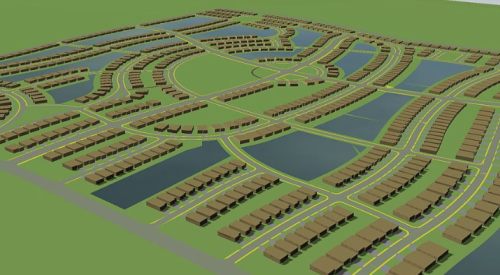

One of 109 homes in Mungo Homes’ Magnolia Bluff. Zoning was for 350 condos, but neighbors still objected to the density. (Photo: courtesy of Mungo Homes)

One of 109 homes in Mungo Homes’ Magnolia Bluff. Zoning was for 350 condos, but neighbors still objected to the density. (Photo: courtesy of Mungo Homes)

How Home Builders Can Play Nicely With Naysayers

In a classic standoff between developer and community—one with elements that evoke the Dr. Seuss story The Lorax and even attracted a tree-sitter—the Portland, Ore., neighborhood of Eastmoreland obstructed development by Portland-based Everett Custom Homes. With block after block of bucolically sited single-family homes with a median value of $761,200, according to Zillow, Eastmoreland residents complained to elected officials about density and outsiders parking their cars on Eastmoreland’s streets after a public transit station opened nearby. Vic Remmers, co-owner and president of Everett Custom Homes, in Portland, bought a double lot in the neighborhood with a century-old house that had been vacant for some time and was occasionally occupied by homeless people.

Outreach 101: A Crash Course

Whether you’re a Housing Giant building on thousands of acres or a small builder with a single lot, count on some opposition to your project. Below are questions that should be part of your project’s site research, followed by recommendations for outreach.

Due-Diligence Questions

• What’s unique about the area? Is there historical, architectural, cultural, or physical significance?

• Was anyone else’s development turned down before and why? (The answer can reveal who are the key communicators for that community, says Sara Ellis, VP of Roni Hicks & Associates.)

• Who are the quiet leaders of the community?

• Who are the planning and zoning board commissioners? Are they there out of a sense of public service or do they have aspirations for higher office? (That commissioner you’re working with could be a future mayor.)

Multiple bidders were competing for the property, so Remmers couldn’t engage with neighbors before buying it. After closing the sale, at community meetings he divulged plans to tear down the house and build two new homes. Some residents were cheered by the prospect of an unsafe blight being removed. But many others rushed to oppose the plan because it included cutting down three majestic sequoia trees on the border of the two parcels. Opposition quickly grew from merely the neighborhood association appealing to the city for a delay to throngs of Portlanders joining Eastmoreland residents and sneaking through temporary fencing to stand underneath the sequoias when tree removal crews arrived. Police were called to cordon off the site, but protests persisted and an environmental activist whom the protesters dubbed “Lorax Dave” climbed high into the branches of one of the 150-foot sequoias and stayed there.

The standoff attracted news coverage and social media attention, some of which painted Remmers as an evil developer and the Trump of Portland. Among the voices were supportive residents and housing advocates seeking options in a growing city experiencing a housing shortage. The animosity caused the mayor to ask Remmers to delay demolition. Eventually Remmers sold the land to the neighborhood association, which intends to turn it into a public park. Despite months of rancor, Remmers says he’s still on good terms with members of the neighborhood association and has even offered to build benches, or some other infrastructure, pro bono for the future park.

Remmers isn’t a novice when it comes to engaging a community. He regularly reaches out, as evidenced by a project he worked on a couple of years prior in which he presented a proposed five-story building with 68 studio apartments. The neighbors didn’t like his plan. But instead of filing a lawsuit or land-use appeal, they wrote a six-page letter with suggestions for improvement. Remmers scrapped his original plan and hired a new architect to design a building that included the neighbors’ suggestions, such as bigger apartments, more bike parking, and a board showing arrival/departure times for the nearby light-rail line. “That happens all the time when we go to a neighborhood to talk about initial plans,” Remmers says. “We’ll make changes if neighbors have great ideas for a better way to do the project. A lot of times they make the project more successful because they know that neighborhood better than anybody.”

Showing, Not Telling in a Community Development

Dan Gainsboro, founder and CEO of Now Communities, in Concord, Mass., envisioned a cottage community with two- and three-bedroom homes with shared gardens, walkways, and parking. But the Boston area’s first pocket neighborhood would require getting the planning commission onboard. Neighbors voiced concerns about density, traffic, property values, and changes to their view.

Having served on the planning board, Gainsboro was familiar with Concord officials. After getting the land entitled and the needed approvals from municipal boards, he reached out to the neighbors in two groups: the direct abutters and the larger group who lived near the site. Initially he wanted to engage the entire community, but his legal counsel recommended inviting the immediate neighbors to the first community meeting since the larger group could be unpredictable. Some residents from a nearby condo attended that session anyway. Gainsboro listened to their concerns and offered to meet with the larger group at their condo complex.

“[Meeting on their turf] meant a lot because all they had before then was one resident’s take on the project, and he was stirring the pot,” Gainsboro says. “But as people began to see what I was willing to do, the tenor of the interaction changed.” Gainsboro also recruited Seattle architect Ross Chapin to help design what eventually became Concord Riverwalk and to present the pocket-neighborhood concept to city planners and the community. As an experienced pocket-neighborhood developer in the Northwest, Chapin had more credibility than Gainsboro in the eyes of the community. It was Chapin who showed residents that his communities—with homes scaled down and tighter setbacks—actually appreciated in property value. The pair made a case that walkable Riverwalk and its connections to public transit and downtown wouldn’t add to traffic, and Chapin explained to the fire chief how emergency vehicles could get in and out.

Chapin also sat in the living rooms of neighbors and presented photos and drawings to show what their across-the-street views would look like and to prove that they wouldn’t have cars and garages bearing down on them. By the next hearing, a few neighbors showed up and spoke in support of the project. Gainsboro had taken the steam out of any opposition.

Now Communities’ Concord Riverwalk won approval thanks in large part to a sensitive, systematic approach to opposition. (Photo: Nat Rea)

Now Communities’ Concord Riverwalk won approval thanks in large part to a sensitive, systematic approach to opposition. (Photo: Nat Rea)

Chapin later partnered with a developer where the land causing pushback from locals was a parcel that residents felt they owned, as it was part of the small town’s open space and had many trees. The developer proposed a subdivision that would have cut down many of the trees, maxed out the property with rows of houses where bedroom windows looked into bedrooms next door, and streets were lined with garage doors. Neighbors vehemently opposed the development and the zoning board rejected the plan. The developer sought Chapin’s help. Chapin suggested having the houses face a pocket park but said he wasn’t going to work with the developer until they met the neighbors. A community meeting was set at a children’s theater near the site. Chapin purposely picked a neutral location rather than city hall, which “is a space where people are sitting in front of desks or conference tables and the audience can only speak when asked. It’s too formal and sets up an adversarial relationship,” he says.

About 40 people attended and were given index cards on which to write questions and comments. Chapin posted large sheets of paper on the wall labeled Concerns, Issues, Needs, and Ideas and wrote on the sheets. The group discussed. He also posted the content to a private website and invited neighbors and planning committee members to give more feedback. Next, he sought out stakeholders who didn’t attend the meeting and drew out their issues: traffic, keeping trees, the impact of construction on a well-water recharge area, and the desire for affordable housing for elderly parents and adult children. “I took that to the developer, and we came up with solutions,” Chapin says.

Chapin showed sketches of site plans and housing types at public meetings rather than finished, professional-looking renderings, which could connote that the project was a done deal. The sketches were always deliberately unfinished, to reinforce that the project was a work in progress. Eventually Chapin and his client presented a plan that provided the density the developer wanted, saved most of the trees, offered a variety of housing types with enhanced buffers and walkable connections to a nearby school and downtown. The audience applauded.

Understanding Objections to Development

Not only can performing due diligence on a community identify the players and red flags, it can also reveal chances to win support. A significant component of Sara Ellis’ research is going door to door to talk to every resident abutting a development and to show them renderings of proposed properties and preliminary site plans so they can see how their properties relate to the proposed project. Often Ellis is invited to sit at a resident’s kitchen table or in their backyard to look over a zoning or site map, and she’ll use that opportunity to interview them.

That’s how Ellis discovered that residents of a community next to a proposed development were worried that the new development would lengthen their evacuation time in the event of a wildfire, since they were living in an active fire corridor with only one way in and out. Armed with that information, Ellis would recommend that her client’s land-planning team include more ingress and egress routes so their development could provide a benefit to the neighboring community, which, in turn, could potentially motivate that community to support the project. “I could have looked at maps all day and would never have known about that concern until I had the real story,” Ellis says. “We would never have known this unless we walked door to door.”

Outreach 101: Engagement

Tips for Engaging Public Officials and the Community

• Share everything and answer all inquiries—people will assume the worst if they don’t know what’s going on.

• Don’t be “archy,” says Seattle architect Ross Chapin. Drop the jargon and use plain English when presenting to the public so you don’t appear arrogant or as if you’re talking over their heads.

• Don’t overwhelm public officials with information. They’re busy dealing with a multitude of other issues besides your project. Ken Ryan of KTGY Architecture + Planning recommends keeping the message simple with visuals and bullet points.

• Use the municipal/county staff as a resource to research the community and the predisposition of public officials. Keep this information confidential. Your sources need to know they can share information with you without any possible backlash.

• Sometimes when development opponents raise crime concerns or say that they don’t want “those kinds of people” in their neighborhood, they may be revealing a core fear that their property value will decline. Ellis says that fear can be turned into a logical discussion about connecting how a property improvement can raise market value.

• There is the organized environmental community and then there are neighbors who cloak their objections to a development with concern for the environment. Treat the environment as another stakeholder in the room. Be sensitive and pay homage to natural resources.

Home Builder Commits to Transparency

Ivory Crofoot, community relations and government affairs coordinator for Neal Communities, in Lakewood, Fla., has sat in many a neighbor’s kitchen, stood on their deck to check out their view and monitor construction noise, and even met on walking trails to get ideas for adjusting the trail map so the paths are less invasive for nearby residents. Crofoot provides her phone and email contacts at all meetings, so it’s not unusual for her to start her workweek with more than 30 emails, voicemails, and texts from neighbors with questions regarding a particular development.

One way the builder engages the community is through a unique format for community meetings, which Neal Communities calls “the stations of the cross.” Meetings are held in a convenient location such as a community center or church near the development site. The session starts with a brief introduction of the development team. Rather than staying at the front of the room and launching into a PowerPoint presentation, the team disperses to stations or tables around the room with visual displays about various aspects of the proposed project. “If a person has a question about a buffer, they don’t have to sit through a 20-minute presentation,” Crofoot says. “They can go to the station with the buffer graphic and ask the engineer. These meetings provide an intimate experience for residents, who can ask about concerns and leave feeling like somebody listened to them and their questions got answered.”

If your project is facing extreme NIMBY pushback and environmental criticism, Ryan of KTGY suggests trying to at least neutralize the other side by cultivating as many supporters as there are opponents. Loud voices and opposition leaders may not represent the majority. A tactic he uses to find quiet supporters amid loud opposition at a public meeting is interactive audience polling and instant displays of the vote tally. Someone who favors a high-density project with attractive amenities may be unlikely to take to the microphone in a large group and say so. But they can click a handheld device to vote when asked during a presentation whether they like the project.

And instead of talking about how great a project is, developers and builders would do better to focus on the benefits their development will bring to the community: a dog park, a long-desired road extension, or, as in Ellis’ example, more evacuation routes in a fire corridor. Presenting from that perspective gives municipal and county officials excuses to support your work. “Find out what your public benefit is,” Ryan says, “and sometimes it doesn’t [even] have anything to do with your project. But the public benefit can help you go a long way.”

For more data and analysis of the 2017 Housing Giants, see these related articles:

- 2017 Housing Giants Rankings

- State of the Industry: Slow But Steady

- The Housing Industry's Age of Acquisition