| The Episcopal Diocese of Chicago sold this four-story building, next to St. James Cathedral, that it used for office space in exchange for cash and new office space in a larger, residential building. |

The best parcels never make it to market. Developers know from experience that deals for choice land often start as solutions brought to landowners who initially have no intention of selling. This is particularly true when it comes to downtown infill sites, says Martin Stern, executive vice president of U.S. Equities Realty in Chicago. At the Urban Land Institute conference on developing infill housing, Stern last month identified six not-so-obvious sources that residential developers should tap when looking for urban land.

- The school board.

- School districts are typically among the largest landowners in most urban areas. As times and neighborhoods change, land once needed for a planned school languishes on the balance sheet. School systems also are chronically cash-strapped. Builders should look for opportunities to lock up key locations and put money in the board's pocket to upgrade existing schools or build new ones in other locations.

Stern cites the example of a razed-school site, near a Chicago shopping district, that his company purchased and developed as low-rise luxury condominiums. In another former school location, a developer struck a deal with the board to build affordable, market-rate detached housing on surplus school land.

- Synagogues, churches and religious organizations.

- In most cities, established religious institutions sit on valuable real estate beyond the footprint of their sanctuary. In some high-density situations, air rights can be sold. Stern recalls a recent deal in which an Episcopal diocese sold its four-story office building for cash and office space in a larger, residential and office building at the same location.

Stern points out that many times these institutions have obsolete facilities and a need for expansion and want to raise funds to support their mission. New structures often can be built with capital from the sale of property. Builders should point out that new structures tend to capture the imagination of congregations when it's time to raise funds needed for a new building. "When it comes to fund raising, new buildings do better than rehabilitation and repair projects," Stern says.

- Not-for-profit agencies.

- Service agencies often hold title to prime residential and mixed-use sites. Many, such as Salvation Army facilities, were established decades ago in locations where they could best serve constituents. Now many of these areas have gentrified. A builder and developer's pitch might be to offer more money and an alternative site closer to the constituency. Stern says this formula has worked in three instances in Chicago.

- Mixed-use developments.

- Cities often em-bark on mixed-used developments through the use of eminent domain but focus on the retail aspect while the residential component withers. Developers should push for more robust housing plans with a pitch that housing will attract better, stronger retail.

"Office buildings, de-partment stores and retail, even cultural institutions, make for great 12-hour downtowns," Stern says. "It takes in-town residents to make an 18-hour or 24-hour downtown that feeds retail, restaurants and cultural institutions, attracts jobs, provides tax revenues, supports schools and builds neighborhoods."

- City-owned property and former public housing sites.

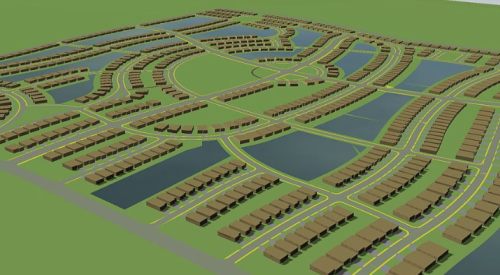

- Troubled high-rise public housing projects such as Chicago's notorious Cabrini Green are making way for new low-rise and townhouse communities with affordable and below-market-rate components. With a critical undersupply of housing in some gentrified areas, market-rate units next door to affordable units have sold well, says Stern, and cities are eager to encourage mixed-income neighborhoods.

- Property that can be replanned or re-zoned.

- Cities are often reluctant to rezone unused industrial properties in the hope that a white knight will come in to add working-class jobs. But municipalities yield the edges of these industrial zones to housing when a good plan is offered. Stern advises that patience is required when dealing with the bureaucracies of city governments.

"Much of the best real estate is in the hands of institutions or is zoned for other uses," Stern says. "The deals can be complicated, but you may need to solve someone else's problem before you can free up a site."