Colorado and Arizona voters last fall resoundingly rejected sweeping, statewide anti-growth ballot initiatives. The failed measures, Amendment 24 in Colorado and Proposition 202 in Arizona, would have required cities and towns to create growth boundaries beyond which growth — and building — would be prohibited, with costly voter approvals required for every exception.

|

The massive margins of defeat in the final vote mask the stark reality that such draconian proposals were popular enough to make it on the ballot. The Colorado initiative, which would have amended the state constitution to control growth and abolish sprawl, actually had a 72% approval rating late last summer before a coalition of development, building and business interests raised $6 million and spent every penny in an advertising and media broadside that finally turned the tide. Amendment 24 received only 30% of the votes in the November election.

Colorado-based land planner David Clinger, 62, a past PB Achievement Award winner, fears we have not seen the last of such anti-growth initiatives, especially in states such as Colorado, where it’s relatively easy to get a measure with even limited appeal on the ballot. He argues that the housing industry, in Colorado and across the country, should support moderate forms of development control legislation that recognize private property rights and provide flexibility to allow local economies to grow and prosper. The alternative, he says, might be facing a day when $6 million is not enough to win.

Professional Builder: What problems in Colorado spurred the popularity of Amendment 24 to the extent that it made it onto the ballot?

Clinger: Colorado is the third-fastest-growing state in the country. Traffic in and around Denver is horrendous. The two major interstate highways here, I-70 and I-25, have had no major improvements in 20 years. Transportation spending has just not been a priority.

You and I know that’s not a problem just related to growth and development, and certainly not just to home building. There are more cars today in every neighborhood, not just newly built ones. But the public perception is that all of the added cars are coming from new residential neighborhoods. So we get blamed for traffic jams.

But you think there’s more to the public’s anger than just road rage, don’t you?

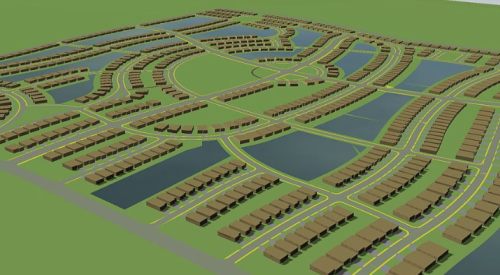

Yes. A lot of what our industry produces is pretty ugly when you see it spread across the foothills of the Rockies. I call it visual pollution. We have wide-open plains around Denver, without the trees that break up sightlines in other parts of the country. Drive around Denver on our interstates and arterial highways and you’ll see it — a sea of rooftops in builder gray. It’s visually unappealing, and it’s what our commuters see as they sit in traffic jams. You really can’t blame people for being appalled.

When you look at it, whom do you blame? The easy answer would be to say mass-production builders who build houses by the thousands, all with hardboard siding in various shades of gray and beige, with too few windows and spindly decks that look like they are attached to the backs of houses with superglue.

It’s not a pretty sight. There’s been no architectural control imposed, and people think these developments are ugly. Even the people who live in them don’t like the way these neighborhoods look from the highway. And they’ve been letting the city governments hear about it.

Now the cities are beginning to mandate architectural controls, like more masonry and 360-degree architecture. Aurora now has an ordinance that requires 40% brick, stone or stucco.

The problem is more acute here because we don’t have trees to hide it, but it’s there in every city in America. The real culprit is probably the FHA regulations adopted after World War II. Those regulations were meant to solve an acute housing shortage when the GIs came home and no housing had been built in 15 years. But those measures should have been temporary. Instead, they became permanent.

What groups sponsored Amendment 24 and supported it?

The Sierra Club was the big one. The Colorado Environmental Coalition, a group headed by nature photographer John Fielder, was another. Less than 1% of the population initially backed it, but then they got a lot of press coverage, and it just took off. It was actually poorly financed. Sierra Club and some other national environmental groups eventually raised about $1 million, which is not much when you consider that they were trying to amend the state constitution.

What turned the tide against it?

State and local HBAs mobilized opposition and finally got the word out that this would be a totally unworkable system. It was estimated that each local government would have to spend an average of $2.5 million to prepare a growth map, and of course there’s no way those maps could ever be done in such detail to deal with every piece of land. But once implemented, it would take voter approval — every year — to change the maps.

Can you imagine every proposed zoning change having to go to the voters? It’s beyond belief. You can’t plan a whole city 10 years in advance.

What lessons do you draw from this experience?

We’d better wake up this year and deal with these issues or we’ll have to deal with another ballot initiative next year, and this time it might be a little less ridiculous than this one. If thoughtful and responsible people don’t craft a solution, irresponsible people will force something on us that we don’t want. We can’t just stick our heads in the sand and hope they go away. The Sierra Club is not going away. They will be back, and they will learn from all the mistakes they made last time.

What advice would you give to individual builders across the country?

Take an active role in trying to shape growth control legislation at the state level. We can’t stonewall the public on this issue. We need to accept that some of what we do now is not good and show that we know how to make it better. Towns, cities and counties do need to plan for growth and control it well so citizens don’t turn hostile. Show goodwill and make it clear that you want to be a partner with the city to solve problems rather than create them.

Here in Colorado, some of our counties are mounting aggressive programs to buy land at market rates to preserve it as open space. They are paying for it with revenues raised via local sales tax increases. That’s a good idea. If the electorate wants open space, they should buy it. Put your money where your mouth is instead of trying to legislate land use.

Jefferson and Douglas counties are doing it. If all the municipalities in America took that approach, the sprawl issue would disappear.