Patrick Zalupski can’t talk right now.

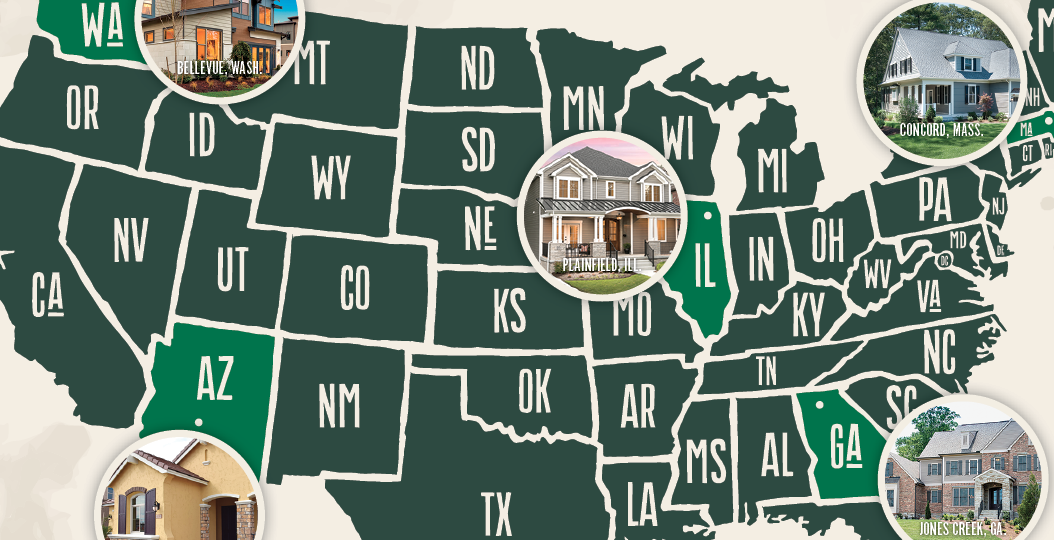

Zalupski, CEO of Dream Finders Homes, in Jacksonville, Fla., politely declined an interview for this story because, as he explained, the company is in the midst of several deals. Already active in 66 communities in seven states (as of late March), expansion-minded Dream Finders is among the regional production builders across the country that continue to make an imprint on their housing markets, despite stiff competition from larger national builders.

There’s no doubt that size helps when national public builders loom in just about every city. (Dream Finders is ranked No. 55 on this year’s Professional Builder Housing Giants list.) Last year at least one, and often several, of the 22 publics were active at 3,922 of the 8,998 communities—43.6 percent—in 34 metros tracked by John Burns Real Estate Consulting in this report. A public builder ranked first in community count in all but three of those markets.

Industry consolidation notwithstanding, however, private builders still have advantages, including closer relationships with local land sellers and being able to act more quickly on deals, says Jody Kahn, an SVP of research at John Burns. “Private builders are thoughtful, creative, and committed to their business,” Kahn says. They also tend to be more concerned with pricing and profitability than the more sales-volume-oriented public builders.

Below, we explore the competitive strategies of five regional leaders that, in an age of mergers and acquisitions, are leveraging their strengths to meet current market challenges head-on.

Conner Homes

Bellevue, Wash.

Last year, prices for existing homes in the Greater Seattle area rose by 12.7 percent. That was more than twice the national average and was higher than any other metro in the country, according to the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller Home Price Index.

The median home price in this market hit a record $757,000. Rents in Greater Seattle also rose last year by 5.4 percent. And despite predictions about a slight cooling down, expect more inflation in 2018, say most market observers. In February, Seattle topped the Burns Housing Market Hotness Index.

Home prices are partly a function of inventory, and in the Seattle market the available housing stock is regulated by growth management laws and boundaries. “As more people move into this market, there’s more opposition to new development,” observes Charlie Conner, owner and president of Conner Homes, in Bellevue, Wash., a company that his father, Bill, founded in 1959.

Conner Homes closed 151 homes in 2017, and expects to close 130 this year, but possibly fewer because it keeps getting tougher to get land entitled and approved for construction.

Conner recounts how it took 10 days of public hearings (instead of the usual one day) in Sammamish, Wash., to get approval for Meadowleaf, a planned community of 113 single-family homes priced in the low $1 million range. Conner Homes also developed this community at significantly below its allowable density.

The builder speculates that jurisdictions haven’t adequately planned for enough infrastructure to accommodate the additional housing needed for a metropolis that has grown to be the 15th largest in the country.

Nevertheless, this spring Conner Homes started selling from one of four new communities it plans to open this year. Its single-family homes range from 2,200 to 4,100 square feet and from $400,000 to $1.5 million. One of those new communities is Materra at Greenbridge, in West Seattle, with 80 townhomes from 1,300 to 2,200 square feet.

With developable land in tight supply, Conner says he is open to all options: “Finished lots, raw land. ... It all boils down to math,” he says, in terms of land and construction costs and current market conditions. Because Conner Homes doesn’t rely on one stock set of floor plans, it adjusts more easily than some other local builders to whatever land opportunities present themselves.

Conner just wishes people would stop talking about “affordable” housing and talk more about “value” housing that, in a perfect world, results in lower home prices by streamlining the entitlement, approval, and appeal processes. Otherwise, he fears, more small builders will exit this market because, he says, “only the big guys will be able to afford building here.”

DJK Custom Homes

Plainfield, Ill.

Chicagoland’s housing market registered slow and steady gains in 2017. Home sales (including single-family and condos) in the city of Chicago increased by 1.8 percent, to 28,621 units, with the median price up 4.8 percent to $285,000, according to the National Association of Realtors. Home sales in the nine counties in the Chicago metropolitan statistical area (MSA) increased by 1.2 percent to 118,131, with the median price for the area up 5.6 percent to $235,000.

While low inventory continues to restrain sales, there has been less demand for pricier homes than for those selling for between $300,000 and $500,000, according to a report from the Regional Economics Applications Laboratory at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. That dynamic could be related to the recent federal tax reform package that limits deduction thresholds for mortgage interest and property tax. About 12 percent of Chicago-area residential properties have property tax bills of more than $10,000 (the tax bill’s new limit), and 11 percent of homes on the market would require mortgages of at least $750,000.

Local builder DJK Custom Homes has been active since 1988, primarily in Chicago’s southwestern suburbs. Its key to longevity and success has been its willingness to customize. “For bigger builders,” says Dan Kittilsen, DJK’s president, naming two Housing Giants building in the area, “customization is nonexistent.” DJK Custom Homes thinks of its floor plans as an idea from which new designs develop.

The builder closed 25 homes from eight communities in 2017, and expects to close 30 this year. DJK’s prices start at around $400,000 and go up to $2 million for houses that range from 2,400 to 6,000 square feet.

Customers rarely buy off of DJK’s house plans, Kittilsen says, preferring instead to tailor their purchases. Lately he’s been seeing more homebuyers who want to downsize but also “scale up” on amenities, among the more popular of which are walk-in pantries, “planning centers” for home offices, and first-floor master bedrooms.

DJK recently retooled its plans so that more of them have very little wasted space, Kittilsen says, meaning they feature open floor plans without formal dining or living rooms. He refers to these models as his “reality” homes.

This builder’s competitive strategy also emphasizes its homes’ high performance. The HERs rating for a DJK home averages 49, compared with 100 for a comparable standard new home in the Chicagoland market. The company’s website—its primary marketing instrument—singles out 26 efficient features in its homes, including Dow Styrofoam insulation board, elastomeric sealant, blown-in cellulose insulation, and energy-recovery ventilation equipment for better air quality.

Northland Residential

Concord, Mass.

Last year, the five counties that comprise Greater Boston saw a 12 percent increase in housing permits issued, to an estimated 12,900. Nearly two-thirds of those permits were for structures with five or more units, according to the Greater Boston Housing Report Card 2017 by The Boston Foundation, Northeastern University, and The Warren Group.

After three regressive years, homeownership inched up to 60 percent in 2017. But sales of single-family homes in Greater Boston unexpectedly dipped by 11.7 percent to around 30,170 units, the steepest percentage decline since the Great Recession. Condo sales were off by 4.1 percent to 18,134, according to the Report Card. The administration of Boston Mayor Martin Walsh has committed to build 53,000 units of housing by 2030. That construction can’t be completed soon enough for a market that ended last year with a paltry 2.1 months of housing inventory.

Northland Residential has seen many ebbs and flows in its markets over its more than four decades in business. This builder and developer, which closes between 40 and 50 homes annually, has weathered adversity by emphasizing the excellence and diversity of its portfolio, and its stewardship of the land it develops, according to Elaine Leonard, Northland’s SVP and director of sales and marketing.

That portfolio runs the gamut, from 5,000-to-6,000-square-foot homes in Wellesley selling for more than $2 million, to 1,850-to-2,100-square-foot houses in South Weymouth with price tags from the mid-$500s to $695,000 that target empty nesters and first-time buyers. A new townhome community in Milton—which is being built under Massachusetts’ Chapter 40B program—will offer four of its 36 units at affordable prices (in the low $200s) compared with its market-rate townhomes selling from $885,000 to $1.05 million.

In Hingham, Northland took over the buildout of Residences at Black Rock, a golf course community where two developers had previously failed. After engaging existing homeowners, Northland eliminated two house plans, reworked two others, and introduced two more with open concepts. It also offered extensive upgrade options. The 52 homes it built are nestled into the existing granite landscape and optimize the view of the surrounding links.

The 26 single-family homes in South Weymouth were built in a community called Dorset Park that’s within a 1,400-acre smart-growth master plan called Union Point. Dorset Park—which NAHB awarded its 2017 Best in American Living Award in the single-family production category—also connects its homes with their environments. The lots, which average 5,000 square feet, were intentionally kept small, Leonard says. Northland positioned the homes so residents can enjoy views of a nearby park from their porches. Tight land availability prevails, so Northland is keeping an eye out for real estate opportunities for townhomes, duplexes, and maybe even rentals in the future.

The Providence Group of Georgia

Johns Creek, Ga.

Much of the talk about Atlanta’s housing market lately has revolved around whether prices are overheating. The decline in home sales during the second half of 2017 fueled that speculation. But this seems like a lot of hyperventilating about a market in which prices rose by 6 percent last year, according to Re/Max, and possibly less, according to other Realtor sources. In fact, Atlanta Magazine answered its own question (“Is Atlanta in a real estate bubble?”) in the negative, by pointing out that average prices are just getting above where they were in 2006. Zillow estimates that in Atlanta last year, 19.6 percent of homes sold above their asking price, compared with 24 percent for all U.S. home sales.

Jeff Kingsfield is one Atlanta home builder who isn’t losing sleep about inflation. But he is concerned about housing keeping up with the influx of people. Kingsfield, COO of The Providence Group of Georgia, notes that even though Atlanta’s population continues to expand—between 2010 and 2017, the 10-county metro added more than 372,000 people, according to Atlanta Regional Commission estimates—annual housing permits issued are only in the upper 20,000s, compared with a pre-recession 15-year average of 45,000 permits.

Over the past five years there have been 95,000 houses started, and last year’s construction barely kept pace with the total in 2016.

The metro’s population growth has created a steady snarl of traffic congestion that has made houses located outside of Atlanta’s urban core less attractive. “People are tired of sitting in their cars for an hour and a half to get to work,” Kingsfield says. “They’ll give up the big yard and house if it gets them out of their cars sooner.” Atlantans, he observes, are imposing geographic limitations on where they live.

The Providence Group, which closed 430 homes last year and expects to close 500 in 2018, has responded by introducing high-density condominium products to its portfolio this year. Kingsfield says one of the company’s goals is to shift its community count—currently about half each of single-family and townhome—to one-third for each and one-third for condos.

“We’re focusing on the ‘new urban-suburban’ market,” Kingsfield says, by which he means suburban areas with urban infrastructure and amenities that will attract empty nesters and Millennials looking for a lifestyle buy. He singles out Alpharetta and Woodstock, two Atlanta bedroom communities, as examples.

For the past five years, The Providence Group has been part of Green Brick Partners, an investment group that owns a majority stake in Providence and in four builders in Dallas, as well as a minority stake in Challenger Homes, in Colorado Springs, Colo.

Kingsfield describes his company as a hybrid that, with Green Brick’s financial backing, has access to capital so it can compete for land with public builders but can also operate its business independently. “It’s a different structure,” he says, “and though the money is more expensive than a bank’s, it’s also recession-proof. It’s been a great setup for us.”

Fulton Homes

Tempe, Ariz.

Between 60,000 and 100,000 people move to the Phoenix area every year. This metro ranked second last year, after Atlanta, for new and existing home sales (124,000 units). In February, Phoenix was among the “Sizzling Seven” on the Burns Housing Market Hotness Index. The market’s affordability is part of its allure; despite a 7 percent increase last year, median sales prices still hover around $250,000.

Several of Phoenix’s larger builders—including D.R. Horton, Meritage, LGI, and Ashton Woods—feature starter-home brands that target renters and other first-time homebuyers. That’s had a big impact on this market, concedes Dennis Webb, Fulton Homes’ VP of operations. Some of Fulton’s communities sell houses priced in the $190s. But Webb claims that Fulton’s homes include standard features that would cost buyers $20,000 to $30,000 more to personalize a competitor’s starter model.

Entry-level customers comprise about one-fifth of Fulton Homes’ business, Webb says. Another 60 percent of this builder’s sales come from move-up/move-down buyers who are typically empty nesters looking to shuck their 4,000-square-foot homes for a cozier but still well-appointed 2,500-square-foot model. Webb adds that Millennials seem to want the same floor plans as downsizing Baby Boomers.

Fulton Homes closed 796 homes last year and expects to close 850 units from a dozen communities in 2018. Despite being swarmed with public builders in the area, Fulton has consistently been more productive, averaging six sales per community per month, compared with the market’s average of 2.7 sales per community per month.

Webb attributes his company’s prosperity in the land of the Housing Giants to “little things,” such as aggressive marketing, sophisticated systems (especially for customer service), and a sales team that averages 15 years with the builder.

Unlike publicly traded competitors that buy finished lots from developers, Fulton Homes prefers to take down larger parcels and master plan them. Typically, Fulton looks to purchase between 400 and 2,000 lots, from which it would form between two and five communities.

“We also try to figure out who the customer is going to be before we buy land,” Webb says. Fulton Homes allows its salespeople to show houses in multiple communities, which gives potential buyers the fullest range of choices.

Another arrow in Fulton Homes’ competitive quiver is its 13,000-square-foot design center, the biggest in the state, according to Webb. Customers have online access to all of the options available at the design center and can get prices before they buy a house, which Webb says other local builders won’t do. “It’s like if you’re interested in a suit at Nordstrom, but the store won’t tell you the cost of the shirt, tie, and cuff links until you buy the suit,” he says. “That’s crazy.”