The scene on this drizzly spring morning in front of DeVos Place, a huge exhibit and event complex in Grand Rapids, Mich., wouldn’t impress the average passerby, yet I am mesmerized. Flowing back up Monroe Street from the entrance, I count 10 school buses, with more queuing up around the corners east and west—at least 15, perhaps 20 buses in all. Each is quickly marshaled up and unloads 30 to 40 students who excitedly line up at the building’s front doors. I watch for about five minutes, and in just this brief time, hundreds of kids disembark. As one bus rounds the corner into the line, another immediately takes its place. I later learn that on this chilly May day, more than 9,000 junior high and high school students will pass through the entrance doors at DeVos Place.

I enter the grand lobby and see tables full of registrations and drawstring backpacks in an array of four colors. The kids quickly find their names and color groups while the impossible-to-miss ushers, who are all volunteers, wave huge “swim noodles” that match each backpack color. Incredibly, despite the cacophony of hundreds of teens simultaneously talking, the students quickly group themselves by vest color. I notice a walkway above the grand entrance hall that affords a better view and find my way upstairs. Looking out across the expanse below, I now notice a few hundred more students grouped at the west end as well that I hadn’t seen when I was downstairs. What a sight!

As I start to wonder how this is all organized, music begins to blast through the loudspeakers and on cue, doors open and the noodle-wavers lead their groups into the exhibit halls. By the time I get back downstairs, almost all of the students are inside, and while I’d hoped for at least somewhat-controlled chaos, what I watch is as close to choreographed ballet as you get with teenagers this side of North Korea. The marquee above proclaims “Welcome: West Michigan CareerQuest 2016!”

In the hall, the four colors the students wear correspond to the colors of four industries, and that shows them where to start. The four industries are: advanced manufacturing, construction, health care, and information technology. Each group gets 30 minutes to spend in each sector, and when the music starts again, they rotate to the next industry. Now, you may presume that with students of this age, construction takes a back seat to the more glamorous health care and IT exhibits, but you’d be wrong. Construction is packed, and the kids are engaged, animated, and having fun.

The Lecture-Free Zone

No lectures here. This is hands-on stuff and the students are busy. One section proclaims “Become an Electrician!” and kids line up to play a cool game where you have to throw switches and select wires in different combinations to complete a circuit. Each kid I watch smiles broadly when the lights and sound indicate success. For those who want to go deeper, a young man enthusiastically explains a portable power management system, the kind used in emergencies—and yeah, he knows how to relate this to the kids’ world. “What happens if a big storm hits and you’ve got no TV, no computer, and your cell phone runs out of power?”

Passing by a masterfully done framing and drywall exhibit, students use power drills to drive drywall screws through the wallboard into studs, and they love it. Just as many girls as boys take their turn. A guy at the concrete area shows a cool new electronic leveler that shoots signals to receivers around the hall to get elevations exactly right. Also on display is a huge ride-on concrete finisher with a big video screen alongside showing how this machine speeds up finishing time by more than 500 percent. If you think these students would be bored by concrete, you’d be totally wrong.

Zip and Ratchet

Next, I’m drawn to a big wooden deck with rails and the continual “zip-and-ratchet” sound of Milwaukee screw guns. Three or four kids at once run deck screws into the planks in less-than-more of a straight line. The guns are stand-up self-feeders, and the bright yellow strips of gold star-bit screws go fast. The kids beam when they get it right, and if you’ve ever done it, you understand. It’s that particular feeling when the screw bites at the right speed, then almost magically pulls itself into the wood and finishes with a high note that says, “Good job!” OK, it’s hard to explain, but you know it when you hear it. For these students, it’s a new experience that puts grins on their faces. I watch four 20-something guys help the kids, explaining the methods and the tools and talking about lumber, screws, building process, and all manner of things that I’m sure the kids’ parents would find hard to believe these students care one whit about.

I see the “old guy” in the bunch, must be 35, and introduce myself. Chris Heyduk is marketing manager for Zeeland Lumber & Supply, the stalwart West Michigan firm that built this exhibit. He describes how Zeeland is a big supporter of MiCareerQuest. “After all,” he says, “Who’s going to install all the materials we sell and deliver to builders?” He points out the other guys from his company who work with the kids. They’re young and casually but sharply dressed with MiCareerQuest shirts and slacks, all smiling, talking, and listening to the students while helping them run a never-ending series of deck screws into the planks. It’s noisy, in a good way. Then Chris makes an interesting point, which I try not to take personally. “See how young our team is here? That’s no accident. The average framer is in his mid- to late 40s. Brickmasons average around 55! The industry is aging at an incredible rate. We want these students to associate construction with young faces, not the old guys.” Looking as serious as I can, I ask, “So you’re saying old guys like me shouldn’t hang around the booth too long?” Chris just smiles in response.

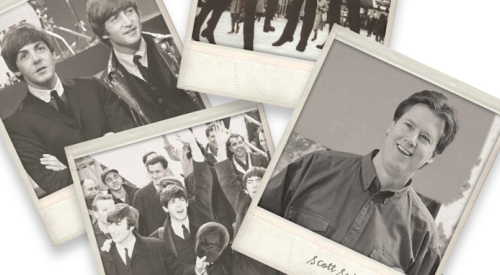

The Pied Piper

Now I spot the builder who invited me to this amazing show. John Bitely is president of Sable Homes, the third largest home builder in the Grand Rapids area. A couple of months back, John read one of my laments here in Professional Builder about how the entire industry has dropped the ball on trade development. He called and challenged me to get over to Grand Rapids for this show, just two hours across the state from me, and learn something. John’s attitude was so infectious that I couldn’t say no. I watch John now as he engages with a group of five students. He sports a big smile, looks each of them right in the eye, explains the high points in the home building exhibit, and leaves them thinking home building may just be a cool profession after all. A big, colorful board stretches along the back of the display showing specific trades at work while pop-outs show how much money, on average, each earns annually in the Grand Rapids area. To these students, it looks like big money.

One kid, I’d guess a high school junior, asks John how much it costs to become a tradesman compared with going to college. John explains that it’s anywhere from nothing—although you get paid less when learning—to some number of thousands to get a specific trade certificate at the local vo-tech or junior college. But it’s certainly a tiny fraction of the $12K to $50K annually it costs for traditional four-year college degrees. John is careful not to denigrate the college degree, but points out that too many kids go off to college with no plan, leave with $50K to $100K of debt, and can’t find the job they hoped for. He compares that to learning a trade, where you make good money right away and have the opportunity to have your own successful, high-paying business by the time you’re 30—with no debt. Now he points out that Grand Rapids was named by Forbes magazine as the No.1 housing market to invest in for 2016 and how much opportunity there is right here, close to home. I look at the kids. Clearly, he has them thinking.

John’s enthusiasm and energy are unfailing as I watch him work multiple groups. The kids all listen. For most of them on this day, they hear about job options they’d never considered. Whatever they decide, how much better is it that they’ve learned about opportunities in building as well as in health care, manufacturing, and information technology, many of which don’t require a full four-year degree?

Out front of the Zeeland booth I now watch another animated fellow with a group of willing students. When we exchange business cards, I learn that his name is Tom Pueler and that he’s from Fox Brothers, to my knowledge the largest supplier of roofing and siding in Michigan. With four sites covering most of the state, Fox Brothers is a material supplier only, and all of its material is installed by subcontractors who are usually directly hired by the builder. Yet Tom’s job is to spend almost all of his time helping those subcontractors find, develop, and train good workers. How progressive is this? While it’s obvious that suppliers have a vested interest in the quality of independently contracted installers, I’ve never before heard of a supplier directly working with them—unless they’re captive crews. Tom spends a ton of time talking to kids about construction opportunities and how to get qualified. He proudly relates how he brought five female students into the business in recent months. Tom also spends a lot of time talking with high school counselors and reports that they’re beginning to see the folly of the “four-year college or nothing” thinking that’s so prevalent with students, teachers, and especially parents.

John grabs me again saying there is someone I just have to meet. We cross the floor and I’m introduced to Jen Schottke, a tall, striking woman with a presence that says, Things are going to get done. Jen is director of workforce development and external affairs for ABC—Associated Builders and Contractors—Western Michigan. ABC is a pure commercial construction association and John and Jen tell a tale that’s hard to believe. Historically, HBAs and ABC have seen each other as rivals for trade talent. To their knowledge, this is the first time ABC and NAHB chapters have actively worked together on trade development. Jen tells me so much about everyone who came together to make MiCareerQuest happen—more than I can write and more than I can cover in this article—a consortium of committees, companies, trade schools, community colleges, builders, suppliers, trades, and of course, associations. Last year around 6,500 students participated. This year more than 9,000 signed up and, as a bonus, the group with overall responsibility for the event, West Michigan Works, added a “CareerFair 2016” from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. where job seekers will be able to connect with employers in the four industries represented.

I stayed at MiCareerQuest half a day and marveled at what I witnessed. The energy of everyone involved was contagious, and I didn’t find a single cynic. This year Kalamazoo will hold its first CareerQuest event, with Lansing planning to launch in 2017. When I wrote the first two articles on the growing and crippling nationwide trade shortage (“America’s Trade Shortage: Failure of an Industry,” in the March issue, and “Brick & Kick, Open the Borders or …?” in May) I made an appeal to anyone doing anything special—and effective—in the arena of trade development to contact me in hopes I could feature them in an article. I learned about great work being done in far-flung places, from northeast Nebraska to far southern Arizona and Texas Hill Country to, of course, Grand Rapids. And there are many more out there. As much as I’d love to feature each one in this monthly column, that’s not really practical. The takeaway here is that you don’t need to reinvent the wheel. Help and experience is out there, if you know how to find it. What’s needed is a searchable national clearinghouse where anyone can go to find which associations, builders, schools, and individuals are making things happen. In my view, the only logical place for that to reside is with the NAHB.

The Challenge … AGAIN

I hate to put any negative spin on MiCareerQuest, but it does highlight issues that must be confronted. At this remarkable event, just one local builder of significance was involved. One. Why not five or 10? There were a fair number of commercial suppliers and contractors, but just a few on the residential side. Why not 15 or 20? There was no one there from NAHB national, the state of Michigan HBA, or anyone from the Detroit side of the state, which is far larger and is also desperately seeking trades. I challenge you: How can this be? At a recent event in Florida, I asked the 75 builders from around the country in my session to show me something concrete and specific they’d done in the past two years to develop trades. There were many good builders in that room, yet the number of hands that went up was zero. Stunning, depressing, mystifying … pick your morose adjective … they’re all appropriate and well-earned.

A builder friend suggested that my assessment in previous articles was a bit harsh. Was I too harsh, really? So let me apologize—for not being harsh enough. And I defy anyone to prove me wrong. Home building sat back and watched its most precious resource dwindle and has done next to nothing about it, save the efforts of a few heroic folks working without much support in the hinterlands. Yet the experience of the folks in Grand Rapids and other places proves there are models that work, models that, if adopted at a level of critical mass, could solve much of our trade shortage—maybe even all of it. We are builders. We are attracted to this industry because it’s hands-on with a physical product people love. We make things happen. We fix things. Isn’t it about time we quit complaining about the nationwide trade shortage and fix it?