| Two basic plans expand to ten floorplans with options for a first or second-floor master suite, finished attic/loft space, formal or informal living areas and a home office. Exterior choices, op-tions and upgrades, such as a tumbled marble master bath or home theater system, further ex-tend the possibilities.

|

It was a pretty tricky little piece of property. Nestled just between the posh town of New Canaan, Conn. and the more diverse city of Norwalk, the 11-acre parcel that Jerry Effren of West Greyrock Development had his eye on was problematic at best. It took smart planning and developing - and some smart negotiating - to find a solution.

The property has a diverse history. Possible uses for the site have ranged from a post office to a hotel to an assisted-living facility for the elderly, but it was controlled for nearly 30 years by one developer whose many proposals for housing developments had been continually shot down.

After finally getting approval for an 18-home project, the developer allowed his permits to lapse and the city, apparently tired of his game, refused to renew them. He took the city to court, and when the property caught Effren's eye, it had already been in litigation for six years.

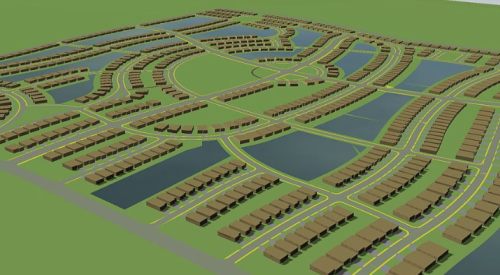

| The 17 homes of the cluster development are arranged to capture the best views of the 4 1/2 acre "green belt" adjacent to it, which was do-nated by West Greyrock Development to the Norwalk Land Trust.

|

Part of what slowed his predecessor down, and, Effren feared, might similarly halt his efforts, was a 33-member group of neighbors that had banded together under the name " Preserve Our Properties Association." As in many areas of Connecticut, says Effren, Norwalk''''s strong coalition of neighbors has a strong influence on the approval process. The main concern of this group was the preservation of open space in a spot that had been vacant for years and protection of property values.

In addition, the land itself held its fair share of challenges. What had always been a swampy, uneven piece of ground, was truly an eyesore after years of sitting idle - it had become a dumping ground for large boulders and similar debris. Even so, Effren thought, it was worth going for. Planned to bridge the pricey housing of New Canaan and the costly, but not outrageous homes of Norwalk, the project Effren had in mind, called New Canaan Way, would be a perfect match for the site: single family, detached homes with lots of amenities in the high $400,000s to low $500,000s.

Aware of what he was up against, when Effren came to the city about buying the land, he he was armed with not only a well thought-out plan, but also an open mind. If he could fulfill the terms of the litigation suit and the buyer would sell, the city told him, he could have it.

First, he reduced the number of houses in the project from his predecessor's projected 18 to 17. Then he forwent plans of his own to build a tennis court and nixed plans for certain outdoor lights. Finally he promised to relocate the development's entrance. When the site was laid out six years before, the location of the entrance worked, but since then an off-ramp from the highway had been added and a new entrance would make things run more smoothly.

Once the city was satisfied, Effren had to woo the neighbors. "I had to convince this group that what I was proposing would be good for the area, the lesser of two evils. After some give and take, they were actually thrilled with the end result."

His flexibility and innovative thinking, coupled with their genuine interest in his project helped speed up the approval process to four short months - impressive for any development, but especially for one with a history like this one.

Having been concerned for many years about the quality of any development that would affect the value of their properties, the neighbors were pleased with what West Greyrock had to offer. After visiting similar projects the company had done, they were able to get a feeling of what the project might look like. They also liked the idea of adding a higher price point to their area, and they hoped that Effren's development would set the tone for future projects.

To satisfy the neighbors' desire for open space, Effren donated 4 1/2 acres of the property to the Norwalk Land Trust, a land protection group that has been deeded a total of 55 acres in its 25 years in Norwalk. This was an especially desirable piece of land for the trust to acquire because not only does it have a brook running through it, but it also adjoins property already owned by the land trust, creating a stretch of contiguous green space along the development.

The donation qualified the development for participation in Norwalk's conservation development zone, in which at least 50% of a development site must be donated to the city, a private land trust or homeowners association. In exchange, he was granted cluster zoning, which allowed him to build at a higher density than typical developments, thus reducing his infrastructure costs.

After succeeding in pleasing the city, the neighborhood group and the Norwalk Land Trust, Effren turned to improvements of the land itself. After clearing the property of its accumulation of boulders, he spent $350,000 in wood and concrete reinforced steel pilings alone. "The land was low and flat in some areas. I had to put in piles up to 62 feet deep to change the elevations so that I could add basements and contours."

In addition, he relocated the entrance, replaced the infrastructure that the previous developer had put in, installed a sewage pump station and brought in 40,000 yards of material for grading. In the end, he says, the cost of land development was almost 20% more than his normal costs.

The rewards, of course, made the challenge worth it. With homes base priced at $555,000, and an average price of $649,000, West Greyrock sold $5 million worth of housing within 60 days of opening, despite the fact that market demand and costs drove prices higher than the company had anticipated.

In addition to the choice in floorplan options and amenities in the 2,700 square foot homes, what people really liked about New Canaan Way was that it was low maintenance. The cluster concept works with what is called a limited common element, which is similar to a lot in that homeowners have the exclusive use of the land immediately surrounding their home, but the land is actually commonly owned. A homeowners association is then responsible for the maintenance of the land.

"Today people are liking the maintenance-free aspect that comes with the cluster concept and a homeowners association," says Effren. "They realize you give up some privacy but don't really mind because they like the common maintenance."

New Canaan Way was applauded by both homeowners and neighbors, as well as by the Home Builders Association of Connecticut who named them "Best Cluster Development" for 1999.

West Greyrock is repeating their successful development formula elsewhere. In the city of Stamford, a nine-home cluster development called MacArthur Park uses the same floorplans and customizing options. Pepper Woods in Stamford and Hamilton Way in Greenwich, with 16 and 18 homes respectively, are both in the approval process.