Operating expenses, as a percentage of sales revenue, should be going down in the robust markets we see across the country today, but instead they seem to be moving in the opposite direction, and that's not the sign of a well-managed company.

Our target for operating expenses is 18% of total sales revenue from home building operations. That breaks down as 3.5% for indirect construction expenses (field operations), 4.0% for financing, 6.0% for sales and marketing and 4.5% for general and administrative expenses. In the past, very few builders exceeded 20% of sales price with the contribution of operating expenses. But our recent Builder Financial Study (analyzing 2003 data from 94 builder clients of Lee Evans Group from all across the country) shows almost 54% had operating expense ratios exceeding the target of 18%, and a full third of them were in excess of 20%.

Inverse Relationship To Profit

The average operating expense for participants in our study was 17.82%, just under the target, with an average net profit of 9.31%. The range among the firms for operating expenses was 7.43% to 28.86%. (The low mark was set by a small volume builder, with little need to spend much in this cost category.)

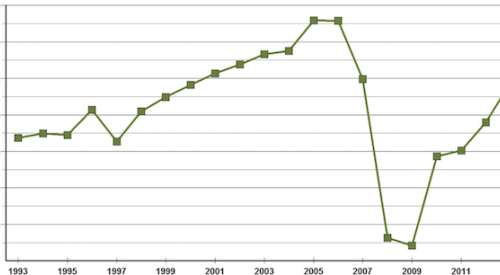

The most interesting thing we see is an inverse relationship between operating expenses and net profitability. The higher the operating expenses, the lower the profit, as can be seen in the chart for quartile averages (on page 55) and the trend line of all participants (on page 55 also).

Dividing the participants into quartiles based on their operating expenses, from lowest to highest, shows a strong correlation to net profits. The lowest quartile had an average of 12.53% for operating expenses and had the highest average net profit of 10.93%. (It's interesting that this quartile also had the highest average net sales volume —$56.6 million.) The second quartile's average operating expense was 16.41%, with the second highest average for net profit — 10.00%. The third quartile averaged 19.50% on the expense side and average net profit eroded down to 7.5%. The quartile with the highest operating expense, 23.57%, had the lowest net profit of only 5.45%.

Here's the kicker. The increases in operating expenses do seem to increase the overall efficiency of the firms on that trend line (shown by a corresponding reduction in cost of sales). However, the reductions in direct construction costs are not proportional to the increases in operating expenses. The chart showing the trend lines in operating expenses and net profits reveals that an increase in operating expenses of 14.5% only generated a reduction in cost of sales of 7.5%. So it eroded net profit by about 7%.

As builders try to take advantage of the strong sales they see in their markets, they appear to become less efficient and effective. They are working harder, with more people, but getting less done—and those results show on the bottom line!

Start packs and purchase orders are late. Construction schedules are extended because support staffs are overburdened and systems are breaking down in the office. Construction supers need assistants, but they are generating fewer houses.

To get the houses delivered on time, builders are hiring punch-out specialists. Because the high volume of work puts power in the hands of trades that are in high demand, builders are afraid to hold them accountable for their work, so instead, they hire extra laborers, on their own payroll, to finish what the trades leave undone.

Financing has been inexpensive, but growth is being financed with debt, so debt service has become substantial. The number of communities has increased, but the yield per community is dropping. The expense load for models and advertising is taking a bigger bite out of every sale. Somehow, builders are managing to get lower results out of more people and higher levels of operating expenditures.

We think that over the long extension of good times in the housing industry, builders have lost discipline.

To break out of this malaise, builders need to get back to the basics of efficient business management and streamline their organizations.

Instead of investing in people to prop up broken systems and processes, either find a new way to operate at the higher level of volume, or go back to the volume — and processes — used before rapid growth messed everything up!