|

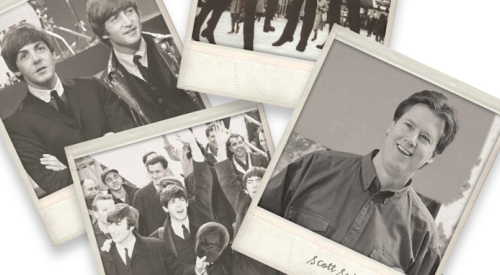

Contact Scott Sedam

via e-mail at scott@TRUEN.com

|

A long, long time ago as an undergraduate at Miami University (the original one by 116 years, the one where athletes actually attend classes, the one in Ohio), I had an excellent political science professor of some renown named Mustafa Rejai.

On one very cold February morning, the Gideons were handing out Bibles on campus, which prompted a spirited class discussion on the impact of religion in politics. Near the end of class, things became quite heated, with students vying to get into the fray and express the wise opinions of 19-year-olds, mostly about how religion has been the source of so much strife on the planet. Then, from out of nowhere, a coed in the front row who had never spoken in class stopped the debate when she asked in a clear and challenging voice, “Dr. Rejai, is it rational to believe in God?”

The class froze. Silence. This was the time of Vietnam, Kent State, anti-war protests and cynicism about anything organized, institutional or traditional. Disaffection was an art form. There was little talk about beliefs, especially belief in God. But the good Dr. Rejai was hardly fazed. He smiled, walked to the board and drew in chalk a diagram he attributed to some philosopher whose name I don’t recall. On one axis of a 2x2 matrix, he wrote “Belief” and “Non-belief.” On the other axis, he wrote “God exists” and “There is no God.” Dr. Rejai then explained the four possible outcomes when you die:

1) If you die, you believe, and there is a God, you dance in heaven for eternity.

2) If you die, you don’t believe, and there is no God, nothing happens.

3) If you die, you believe, and there is no God, you never know the difference.

4) However — and Dr. Rejai repeated the word slowly and with emphasis — how-ev-er, if you die, you don’t believe, and there really is a God ... well then, now you’re in trouble.

As the somewhat nervous laughter subsided, Dr. Rejai walked toward the front-row student, bent toward her and with a wise look said, “And with that in mind, young lady, I suggest that you believe.” He rose back up, opened his arms to the class and asked, “Any questions?” No one said a word. “That’s settled then. Class dismissed.”

It was one of my more memorable college classes, and that morning, more than 30 years ago, comes back to me often during my travels and work with builders. People get classified in a lot of overly simplistic ways. You know, the old “there are two kinds of people in this world ...” Yet when it comes to building truly successful, sustainable companies for the long haul, good times and bad, this simple model works well. There are two kinds of builders in the world: those who believe and those who don’t believe. Of course, that leaves this question: In what?

I have seen a few companies define this with statements on the wall, in brochures or on Web sites under headings such as “We Believe” or “Basic Beliefs,” and I always have been drawn to them. Somehow, a statement of beliefs seems stronger than simply a mission statement, which often merely describes what a company does. I often wonder where these beliefs came from. Did a visionary leader, perhaps the founder, write them? Did a group of employees develop them? Whatever the source, a statement of beliefs sends a strong message about what you will stand up for, fight for and, in matters of politics and religion, even die for. These beliefs are, at times, dramatic, such as the second sentence in the Declaration of Independence:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

When 56 American colonists signed their name to that document, they knew there was no turning back. By publicly stating their belief in independence, they set in motion events that would change the world for centuries.

Most of what builders might write as their beliefs might not sound earth-shattering, but don’t discount the importance of writing them. Remarkably, “true believers” then tend to take the action to make things happen. This does not apply only to broad philosophical positions. It is at least as important to set down some of the day-to-day how-tos about how you conduct your business. I’m talking about the practical things that guide an organization in daily decision-making.

Have you done this exercise? Do you use your list of beliefs to guide you and your company? Is it posted in construction trailers and model homes? Do your beliefs get discussed and challenged? If they are taken seriously, now and then someone will march into your office or a meeting and proclaim how you or the company is failing to live up to one of them.

So that’s your assignment. First, have everyone write down five to 10 basic beliefs, in private. Ask them to get practical and think about guidance for daily work. There will be plenty of 30,000-foot statements on philosophy; getting them to street level is the hard part. Then get together in a group and hash it out, get a consensus and publish your list.

As an example, on a plane recently, I did a quick, one-man brainstorm of 10 things the best builders believe:

1) At the end of the day, 97% of home buyers want what we want as customers.

2) We must spend money to make money ... on people, too.

3) Without our suppliers and trades, our business is nothing. Our actions must reflect that.

4) Winston Churchill was right. Builders who plan do better than those who don’t plan, even though they rarely follow their plan.

5) Training for everyone, new hires in particular, is an investment that produces returns — not an expense.

6) Anyone who spends more than $100,000 on anything has a legitimate expectation that it will be perfect.

7) We must believe in the concept of the perfect house, even if we never see one.

8) Every system is perfectly designed to produce the results it gets. If we don’t like the outcome, we must change the system. Yelling, screaming, memos, contests and bribes won’t change anything.

9) Starting projects before they are truly ready costs us way more money than it saves.

10) If we want people to act like owners, we must give them a stake in the profits.

If you do this in your company, and I hope you will, don’t show anyone my list. It’s important that your employees first develop their own lists, with no outside influence. Put the lists on the walls for everyone to see and contemplate. See what you all have in common. What does your company collectively believe?

But also consider what is missing. On which things — important things — is there no consensus of belief? These very well could be the obstacles holding you back. And if you finish a list of what you believe and feel good about it, e-mail it to me at scott@truen.com. A few of those lists might make for an interesting column.

A caution, though: Putting your beliefs in writing just might start something that could change your world.

I recently called the Miami of Ohio and found out that Dr. Rejai retired eight years ago but still keeps an office and comes in two or three times a week for mail and to check in. He won’t remember me from 1972 because I was in the “major-hopping” phase then, but I will mail this column to him. I don’t know if he still gives advice on believing, but I hope this column will confirm one belief to which most college professors cling: that a student can remember what a professor said 32 years earlier, and it can make a difference. Believe it.