| The inner core of the Glenwood Park plan will consist of row houses, public green space, civic or educational buildings, and shops and offices, with apartments above.

|

Green Street Properties LLC has a pretty sweet deal: a 28-acre parcel 2 miles east of downtown Atlanta, a city where people are leaving the suburbs in droves, in part to escape the standstill traffic caused by sprawl.

Most recently, the site was the home of a concrete recycling facility, but it has a long history of various industrial uses - all of which have left their ugly mark on the site. "This is an area that has been an eyesore for a long time," says Walter Brown, vice president of Green Street Properties. But when Green Street announced plans to develop a new mixed-use community, Glenwood Park, on the site, the company got static from the surrounding neighborhoods. Residents wanted the site redeveloped but were concerned about what kind of development would occur.

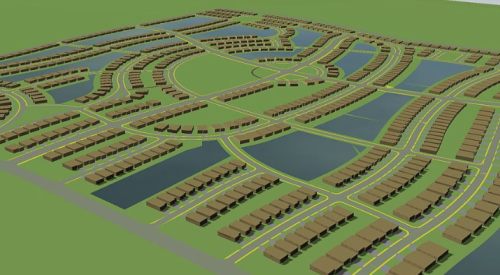

| Green Street Properties' site plan for Glenwood Park - designed by Tunnell-Spangler-Walsh & Associates and Dover, Kohl & Partners - centers around a town square and includes retail, mixed-use and residential blocks. The plan is not set in stone - Green Street envisions organic growth as the community emerges.

|

Brown, Green Street CEO Charles Brewer and president Katharine Kelley were not particularly surprised. They had intended to involve residents in developing a plan for Glenwood Park.

"We look at the impact on the Atlanta area," says Brown, whose company was founded on New Urbanism principles. "We are interested in making it a model of smart growth and sustainability. We are also interested in getting community input, but we're not turning it over to the community to tell us what should happen. We have our own vision for what we'd like to see there."

That vision included a "fine-grained mix" of for-sale and rental housing, green spaces, and office and retail space.

Develop Allies

Many residents liked the idea of a mixed-use development, partly because it mimicked how the rest of the area had been developed. But they were concerned that the height of the buildings would interfere with their views of downtown Atlanta. They also wanted small shops and businesses, not big-box retailers, and were concerned about traffic, safe bicycle paths and walkability.

Green Street's approach to addressing these concerns and gaining support for the community was to identify the key people in the neighborhoods and ask them to act as representatives. Leaders of area business associations and formal neighborhood groups, the chairs of neighborhood planning units and respected residents made up the 20-person Glenwood Park Task Force, which participated in six brainstorming sessions during the four months before Green Street filed its zoning application. From that task force, Green Street chose five people to join the Glenwood Park design charrette, a three-day process led by Dover, Kohl & Partners, a charter member of the Congress for the New Urbanism. The participants came up with a plan that met the goals of Green Street and the community - many of which had been similar from the beginning. The group process refined those goals to create a plan for implementation.

|

The Glenwood Park plan includes single-family and multifamily for-sale housing; market-rate and affordable rental; live/work, mixed-use and civic buildings; green and open space; and office, retail and light commercial space. The street pattern will connect to the existing grid, with streets flanked by bike lanes and bike parking areas. To fulfill a common desire for sustainability, Green Street and the task force decided that all single-family homes would be built under Atlanta's green building program, EarthCraft House, and some nonresidential buildings might conform to LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) standards, a national commercial green building program.

By the time Green Street presented the plan to the larger community, the company already had gained the support of key neighbors and turned potential opponents into advocates.

"I think the neighborhood at large appreciated that their representatives were included from the beginning," Brown says. "The problem is, when you get into these neighborhood meetings, you just don't have a lot of time to negotiate and debate with 40 people in a room."

Brown says builders and developers should choose a task force they can rely on to disseminate information well before town meetings. Task-force members should have a thorough understanding of complex ideas, the pros and cons of various issues, and the serious consideration that goes into each decision so they can explain it to their peers in the community in a language they understand.

"When you're in the meeting presenting a very narrow band of options within your proposed plan, it helps to have buy-in from audience members," says Brown. "If you don’t have buy-in, you're always susceptible to someone saying, 'Hey, why didn't you think of this? I don't know why you didn't look at that.' I can’t be anywhere near as persuasive as when a member of the audience stands up and says, 'Joe, we sat there and debated that very subject for an hour-and-a-half two nights ago, and this is really the best idea. It's what all of us at that table agreed upon.' That will stop it right there."