| The Olson Company founders Steve Olson (right) and Mark Buckland partner with cities to provide new housing for buyers seeking in-town living.

|

Who would you pick for National Builder of the Year in 2000, this first year of the new millennium? Certainly, in the midst of a building boom now nine years old, there are plenty of candidates. Profitable, fast-growing home builders stand out in markets nationwide and among national builders listed on Wall Street. Still, there’s bound to be a certain symbolism associated with the first recipient in a new century of the oldest and most prestigious award in the American housing industry.

When PB editors began deliberations to choose the 44th Builder of the Year, we quickly decided to give real weight to that inherent millennial symbolism, to search through the ranks of profitable, growing firms for a candidate with a new modus operandi - a business model geared to the challenges of a new decade and century.

With cities, suburbs and even ex-urban towns now grinding toward traffic gridlock every workday, we see little chance that the political pressure to limit growth (and home building) will cease. So it was logical for us to include in our search for a millennial Builder of the Year a candidate from the urban infill market niche.

In many areas of the country, such builders not only enjoy great success they are also bulletproof in the political battles between advocates of smart growth and those who want to slam the door on home building to arrest urban sprawl. Infill is seen as part of the solution, not part of the problem. In the Pacific Northwest, where urban growth boundaries are already in place, in-fill is the only game playing in some markets. It’s a hot niche not just for political reasons, but because empty nesters are now beginning to fight yuppies for space in line to buy lofts, townhouses and high-density detached homes within walking distance of work and urban entertainment districts.

When we went looking for a great infill builder, The Olson Co., based in Seal Beach, Calif., but building from San Francisco Bay to San Diego, quickly attracted our attention. This is the penultimate practitioner of urban infill. Olson benefits from an insightful business plan developed in 1988, and from the confluence of powerful California political and market forces that few saw back then except visionary founders Stephen E. Olson and Mark Buckland.

But when we looked closer we found much more than an astute marketer in a hot market niche. There’s much about Olson that builders large and small, in big cities, small towns and fast-growing suburbs, should try to emulate. It starts with understanding the niche and tailoring a company to meet the special demands of it. But it goes way beyond how the company is organized. It is about who works there and why.

This company is not just a collection of people with skills that mesh. It is a cadre of soul mates, all concerned with the problems of cities and the people who live in those cities. They are determined to make these places better, and to improve the lives of people.

We often say that a company should have a mission statement to give every employee a sense of purpose aligned to the needs of customers and the goals of the organization. Olson has much more than that. These employees don’t have a cute phrase, but they are on a mission. They care. If that sounds altruistic beyond belief, talk to them as we did. These are people who believe what they do makes a better world. From the evidence we can find, they are right.

What They Do

| Site-specific architecture defines The Olson Company’s work. Local architects are important partners in the company’s efforts to design homes that meet the city’s needs, blend with the existing housing stock and appeal to buyers.

|

With 110 employees, The Olson Co. will produce 450 for-sale housing units this year, for revenue of about $130 million, in a dozen urban and suburban infill projects up and down California. Remarkably varied in product type, density and architectural style, Olson’s projects not only sell fast, they always seem to escalate area property values. And that often turns one-time opponents into advocates of the firm’s next proposal.

The infill niche, in most places, is dominated by small firms. Most of Olson’s competitors, where any exist, build fewer than 50 homes a year. But Olson proves this is not necessarily a small builder market. Believe it or not, the firm already has enough projects,coming on stream and in the pipeline to project 700 units for $200 million in revenue next year and 1400 units for $300 million in 2002.

"I think the potential is there for us to sustain $500 million a year," says Steve Olson. "And that’s staying within our in-town niche, right here in California. There’s no restriction in terms of opportunity, only process. If we can build the internal processes that will allow us to grow, we don’t lack market opportunities."

We looked at many candidates for National Builder of the Year, but always came back to The Olson Co. When we finally made the call, it was not just for proving that infill is a market with real growth potential, and not just for doing it so well that the company’s design concepts, marketing programs, and finished products set benchmarks for excellence that are almost unassailable. In addition to those strengths, what really sets The Olson Co. apart is its people and the way they operate. The firm turns municipal planners, redevelopment agents and even elected government officials into partners rather than adversaries. And Olson’s employees, many of them former municipal workers, share an almost Messianic sense of purpose - to deliver affordable new housing in communities where, in many cases, none has been built in ten, even 20, years.

Talk to enough Olson employees and it soon becomes apparent that this is not just another production builder. The people are well paid and the work they do is profitable. But they all speak of more important goals beyond making money, even beyond personal fulfillment and creativity. It can only be described as public service. They believe their developments serve a higher purpose, like "bringing new homes to people who never dreamed they’d be able to buy one," and "getting people out of their cars and the endless traffic jams by bringing them a home that’s close to where they work."

After interviews, we often felt as though we were back doing Millard Fuller’s National Builder of the Year story again. These people have the same sense of service as Habitat for Humanity volunteers, and yet, this is a private, profit-driven company. But think about it. Why shouldn’t that be the case? Virtually all builders lay claim to a noble role in serving the public good by producing homes that build the social fabric of America. Why shouldn’t all builders have employees with this same sense of civic service?

Olson did not seek this award. In fact, chairman Steve Olson and president Mark Buckland might prefer to avoid both the scrutiny of our editors and the limelight associated with the award. The work they do is highly politicized and best accomplished patiently and quietly, without bombast or chest-thumping. Thoughtful, quiet and reflective are words that describe Steve Olson’s personality and that of his company.

The key to Olson’s success is the relationships of mutual benefit and trust the firm builds with city officials, community leaders, land owners and neighbors, as well as home buyers. Olson and Buckland prefer to call what they do "in-town housing" rather than infill. Whatever you call it, it is a completely different world from that of the typical suburban production builder. And yet, we think you’ll find Olson’s ideas compelling and valuable, especially in today’s political climate, even if you build much farther from city hall.

How They Started

"When we founded the business in 1988, Mark and I understood that California was probably at the peak of its housing market. We concluded that ‘in town’ was the best place for us - providing a new housing alternative for people who prefer living closer to jobs, entertainment and transportation than in new master-planned communities far out in the hinterland and driving more," Olson says now. "We saw there was tremendous demand for new housing in established towns, and nobody was really filling it."

They also saw some things about California state law that create an imperative for local governments to seek housing development, even in long-established, land-locked towns like Pasadena and Long Beach.

"California’s general planning law requires every county and city to plan how to meet increases in the demand for housing, as well as transportation, schools and other public services," says Juan Acosta, legislative advocate for the California Building Industry Association in Sacramento.

"The California Department of Finance projects how many housing units the state will need from year to year based on U.S. Census data, household formations and job creation. Then regional councils of governments break it down to assign what’s required to meet the housing needs of each county and city," says Acosta. "It’s also broken down by income level - very low, which is 60% of median income or less; low, which includes up to 80% of median income; and middle-income and above, the top level.

"The cities have to submit a plan to the California Department of Housing & Community Development, which then rules on whether each city is planning sufficiently to meet housing needs," says Acosta. "The local government has to do an inventory of the land that’s suitable for residential development, and also look at the zoning and existing services related to those sites."

The other peculiar piece of California law that relates to infill governs the redevelopment process. "Cities have to designate blighted areas, then set aside a portion of tax revenues to fund a redevelopment agency," says Acosta. "And 20% of those redevelopment agency funds are, in turn, set aside for housing, especially low-income.

"The trouble is, many of the cities are way behind on housing, especially ownership housing," says Acosta. "Job creation and household formations in most cities are far beyond the housing component. And the redevelopment agency law has those housing set-asides that are ‘use it or lose it.’ There are billions of dollars in those set-asides just sitting there."

This all helps The Olson Co. find municipal officials, planners and redevelopment agents who are eager to hear the firm’s ideas for ownership housing on the various infill sites the cities control.

How They Think

| The Promenade in Huntington Beach met the city’s need for an affordable housing component in a master-planned community; the design pleased existing homeowners in the coastal enclave.

|

Right here, Olson makes a drastic departure from the standard practices of most home builders. The company, from top to bottom, views the city as its client and partner in developing a product for the home buyer/customer. Think about how that compares to the average builder’s relationship to local planning, zoning and building departments. Olson bends over backward to make its municipal clients happy. Some of what they do in this regard adds costs that can never be recovered. No matter. They must perform for the city, even more than for the home buying customers.

"In the early 1990s, when we really got started, a lot of those redevelopment funds were going into seniors rental housing projects," says Mark Buckland. "That was the easy way for the cities to meet their housing requirement, even though the demographics showed that 85% of the need was for ownership housing for families. When we did our first project in Fountain Valley, our proposal pointed out that the real need was housing for families working in the city.

"With the support of the city, we got that (project) through some neighborhood opposition. It sold out in one day, and it won the California Planning Association’s Leadership Award. The city looked at it as a very positive thing, and we said, ‘Wow, there’s a real benefit associated with being a good partner with the city.’ If you’re just concentrating on building for the home buyer, then you might view the city as an impediment. When you see the city as a client, you realize that success for them leads to another opportunity for you."

From inception, The Olson Co. has had an independent board of directors including some of the top names in real estate, but also a broad cross-section from Southern California business and academic communities. On the board today are real estate consultant Sandy Goodkin; Jim Hankla, CEO of Alameda Transportation Corridor; Dick Cupp, president of First Bank of Beverly Hills; and Jim Wilburn of The Davenport Institute of Public Policy at Pepperdine University.

"The challenge from our board, from day one, was to differentiate ourselves," says Steve Olson. "They told us housing patterns were going to change in California, and that a lot of what was going on at the time in East Riverside and San Bernadino was not sustainable by limited job growth. Traffic now moves at just under 30 miles per hour on our freeways during rush hour. Within three years, the estimate is that average speed will be cut in half. So we are building housing where the jobs are."

How They’re Different

Olson doesn’t carry much land. Most of the sites on which it builds are owned or otherwise controlled by a city/partner until just before construction starts. Olson’s primary up-front investment is the time of highly skilled employees who work closely with city planners and redevelopment agents to take a site from the city’s request for proposal (RFP) through sometimes torturous entitlement processes that can stretch from 60 days to six months. Another big ticket item is the investment in design work by many of California’s top residential architectural firms.

"Probably 80% of our deals don’t require us to buy land," says Dave Schaffer, an architect by trade, and an Olson vice president who heads the "forward planning" team. "About 50% of them come to us through a city’s RFP process, 30% are deals we track down and take to a city and maybe 20% are just private transactions where we find vacant land that we try to get re-entitled."

Most of the time, Olson partners with a city redevelopment agency to take the site through entitlements. "The redevelopment agency is often our ally in working to get rezoning for increased densities through the planning department or city council," says Schaffer. Requests for proposal can take several forms. "More often than not, we are asked to present a conceptual design solution for a site and a financial pro-forma to go with it," Schaffer says.

A big part of his responsibility is deciding which of the architectural firms to use for these designs, then working with the architects to fashion a product that meets the needs of the city, fits the pro forma and also meets the desires of buyers. Thanks to the high-profile stable of architects, Olson’s projects are always beautiful. That helps sell the city and neighbors who are often leery of higher densities.

"When we respond to an RFP, the city will hold a formal review, then issue a short list of finalists. For probably 99% of the deals we have proposed, we are at least on the short list, and then of those, we probably have 90% where we are actually selected. Once that happens, we start down the community meeting path, working with city council people and planning commissions, along with the redevelopment agency," says Schaffer.

Do sites ever involve condemnation processes? "Sometimes," he says, "friendly or hostile. We’ve been down both of those paths, but we try to stay out of that. It’s really an issue for the cities and land owners."

Once Schaffer has a design concept that works for the city, he hands it off to Alex Hernandez, a former Long Beach city planner, now Olson’s director of development, who takes the design concept into the community to see if it will fly with neighbors. But Schaffer is not done with it. "From day one right through to construction, we’re fine tuning the design, trying to match land planning, product types, square footages, etc., to zoning requirements and the demographics of the market," says Schaffer. "We are constantly working to get the city what it wants, and deliver the best value to the targeted buyer."

Olson puts the city and buyers ahead of its own profit. "That’s just the mentality that works in our business model," Schaffer says. This is where Olson’s unique corporate mission comes into play. If the city and buyers did not come first, many of the people who now work for Olson probably would not be there. But there’s another way to look at that: Olson would not hire them if they did not have that unique sense of public service. It’s necessary to do the work.

Asked why he works for Olson, Schaffer says, "There’s no greater satisfaction than going by our projects and seeing how they live and age. You see the people and how they enjoy it. And the projects look so beautiful. I say to myself, ‘I can’t believe how much pain it took for us to get that.’ It’s why I’m starting to get all these gray hairs, but it’s worth it. You watch people spend eight to ten hours a week sitting in traffic... to me, what we do for a living is enhance quality of life. We bring housing to the job centers, so people can back away from reliance on their automobiles."

Steve Olson explains the logic behind this corporate psychology: "The worst thing for us is entering into a development agreement with a city and not being able to fulfill the agreement," he says. "Our reputation is based on completion at or above the city’s expectation. Because of networking, our reputation is critical to our ability to keep doing this work. It’s everything."

When Hernandez goes into action, there’s a design concept, a pro forma, an assessment of a political base for the product, and a schedule, but no final knowledge of how it will play in Peoria. "My first action is to show it to the neighbors. Sometimes, if they live in $500,000 houses, and we are proposing small lots and houses selling for $300,000 to $400,000, we have to go back to the drawing board. And that means taking a new design back to the city."

Like Schaffer, Hernandez has a strong sense of mission that sounds very much like public service. "We put the city first on our client list," he says, "because when we’re done with a project, we want our reputation in that city to move to the next city. We want the word to spread that we perform for clients.

"I’m here because of the vision of this company. Hearing Steve talk about providing housing solutions for cities really sold me. Someone has to provide the housing that’s necessary. To be able to see a first-time home buyer move his family into a new home... You hear the kids say, ‘Daddy, mommy, this is our house!’ I get the biggest charge out of it. That’s my reward."

| It isn’t enough for The Olson Company’s team to just understand a specific project; they must grasp a city’s whole vision for its future.

|

It only takes a few hours with Steve Olson to make clear that the company recruits to this psychological profile, and Olson reinforces it with his personal leadership: "If you’re going to be in this business, in this particular niche, if you don’t have a passion for service, you don’t belong here," he says.

Olson, who holds an MBA from Pepperdine, started in business as an investment banker and first got into housing by investing in a manufactured housing firm. "I didn’t grow up pounding nails," he says now. "I got my introduction to housing on the finance side, and because of that, I’ve got a little different perspective than most traditional builders. I see the need for affordable housing in the cities."

Mark Buckland graduated from University of California Irvine in civil and environmental engineering. He worked for the campus architect then managed apartments and shopping and business centers. He worked on an apartment development in Long Beach with a 20% affordable component. "That’s where I got a strong interest for what we’re doing now," he says.

What They Build

The striking architecture is the first thing you notice in every Olson community. Beyond that, each one looks different, as if custom-designed to fit the unique constraints of location, site, client city, pricing strategy and target market. But that impression is not quite accurate. There are lines of continuity linking elements that may not be visible to the eye. "If everything actually was completely different, we would run the risk of building projects where our cost would get out of whack," says Olson. "So we actually have a system of modules that allows us to arrange a combination of those modules for a design solution that looks custom, but is actually made up of things we know how to do."

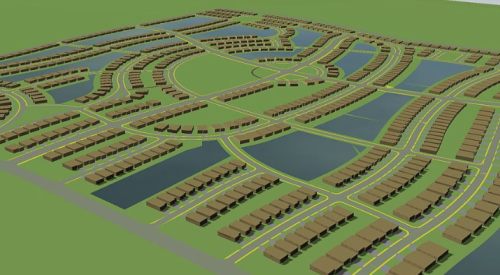

Another link among products is the category of design solution sought by the city. "Neighborhood revitalization, transit village, urban downtown, affordable housing, and urban master plan are all descriptions of designs that our city clients understand," says Olson. "They also represent core competencies and skill sets we have in the company. If a city wants a transit village around a BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) station, we know instantly that we are designing for a buyer who wants convenience more than anything else. If the city wants neighborhood revitalization, we know that it understands it is going to have to accept higher densities to pay higher land values."

Community-Based Marketing

While cities are Olson’s first priority, every project has to have a solid marketing plan based on a keen sense of targeted buyers’ psychographic as well as demographic profiles. Since all projects are located in well-established communities and sell the benefits of location first, it’s no surprise that 90% of buyers come from inside a five-mile radius.

That allows Olson’s director of sales and marketing Lenette Harmer to zero in on the target market with some of this industry’s most unusual marketing techniques. "The majority of our buyers are not even in the market for a new home," she says. "They are living in the community, and have for a long time. In many cases, they have no reason to believe new housing even exists in the community, since many of the cities have not had a housing development in 15 to 20 years. They often see one of our signs and come in, and they can’t believe they can buy a new home there."

Since Olson always sells location within walking distance to many community attractions, all of the firm’s projects now end in the word "walk," such as City Walk in Brea and Summer Walk in San Juan Capistrano. Beyond that link, however, each project is marketed differently, unique to the city and neighborhood each calls home. It is very tight community-based marketing.

"We do a lot of focus groups within the neighborhood," says Harmer, "to learn everything we need to know. For instance, we did one recently in Walnut Park, where the market is 100% first generation Latino. They speak no English and none are now home owners. They are all renters. We didn’t know their culture, so we went to one of their churches and got people from the congregation to come to our focus group.

"We learned that, for them, everything is price and value-driven, and that bed counts are very important."

In most markets, Olson also relies heavily on real estate brokers for information. "We are in many markets that are ethnically diverse, including Japanese, Chinese, Korean and Philippino. We’ve learned that having someone there to translate into their native language is very important. The Realtors who work the market can usually do that for us."

Local newspaper advertising is also important. "We don’t spend a lot of money, but we’ve found that the cities love it when we pump dollars into those local businesses," says Harmer. "Everything we do is lifestyle-oriented. Our buyers are not purchasing because they love a specific floor plan. They buy for the location and the ability to walk to schools and parks and shops."

Much of Harmer’s marketing budget for a project is often spent financing special events that help emphasize how the new neighborhood ties into the existing social fabric of the community. On the day of the grand opening of Artisan Walk in Brea, Calif., for instance, Olson held a "Celebration of the Arts Day" to support the city’s art in public places program.

They Do Make Money

Much of what Olson markets is affordable (by California standards), and sells to first-time buyers, but by no means is all of the firm’s production in that market segment. For example, Maple Walk in Torrance, Calif., has prices starting above $550,000 for plans ranging upward from 2646 square feet. While Olson won’t reveal margins on any project, probably because of the sensitive political nature of its city relationships, everything we know about the infill market in California leads us to believe Olson is highly profitable.

Larry Webb of Irvine, Calif.-based WL Homes is a sometime competitor who has done 20 infill projects over the past decade. "My most successful projects of the 1990s were infill sites," he says. "If you can solve the political and physical problems, there’s never a problem with financial or marketing issues.

"There’s always pent-up demand just waiting to buy in a location that will get them closer to work. Most buyers come from inside a five-mile radius, so you save on marketing costs. You pay more for sites, but the infrastructure is often in place, so the increase in the raw ground is offset by a reduction in development costs. And a lot of times, you can get a distressed site for a lot less than its intrinsic value, based on location.

"You need vision to do this stuff, and Olson has that," says Webb. "They see things that nobody else sees because of the contacts they’ve built up by specializing in that niche. Olson has done the best of anybody, and if you master it, the returns are unbelievable."

While infill is a niche most of builders cannot or should not pursue, we do believe Olson’s modus operandi - treating cities as clients and carefully tailoring the organization to meet the needs of the existing community before those of new home buyers - may be the trendsetter for the 21st century.

Also See:

How We Pick a Winner

Building Brea

The Promenade

Rose Walk