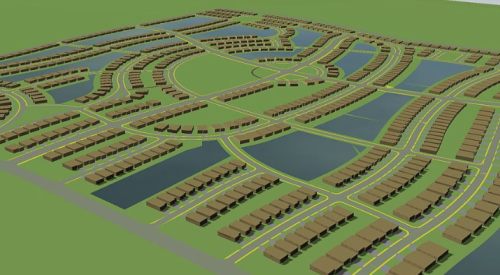

| Townhouses and single-family detached houses sit side by side along Issaquah Highlands’ main park.

|

Washington state adopted the Growth Management Act in 1990 to control the pace of development in its fastest-growing counties, particularly in the Seattle area. Under this legislation, local governments set their urban growth boundaries (UGBs).

The law had a significant impact on plans for a new community, Issaquah Highlands, in the Seattle suburb of Issaquah. "Most of this project was in a rural area under the former comprehensive plan, and it used to be very easy to change from rural to urban," says Judd Kirk, president of the development firm Port Blakely Communities. "We were in the process of annexing to the city of Issaquah when the Growth Management Act was adopted." The proposed development raised the hackles of citizens who wanted to hold the line on urban growth, and Kirk realized he was in for a lengthy, controversial permitting process.

Issaquah Mayor Ava Frisinger says that although the city was within the UGB, there were environmental constraints on further growth. "We had a floodplain, a salmon-bearing stream and steep hillsides that were slide-prone and heavily forested," Frisinger says. "It was obvious to the City Council that the least disruption to existing neighborhoods, and probably the least damage to the environment, would best be accommodated outside what were then the city limits and within master-planned communities or urban villages. They seemed like an opportunity to balance housing and jobs and also acquire large amounts of permanent open space."

The approval process involved surveys, public meetings, focus groups, study groups and City Council meetings. Port Blakely offered a number of options, including a suburban golf course community that was strongly rejected. It became clear that local residents were dissatisfied with the recent pattern of suburban growth, which translated into large, sprawling lots and traffic congestion. What they wanted was a more compact, mixed-use community with shopping and other services.

"This was an area that was undeveloped, though there were some small ranches nearby," Frisinger says. "I heard from the existing residents and people in the broader community, and they talked about the various things they identified as being part of Issaquah and wanted to retain." Study groups were formed to examine a range of issues, from groundwater and aquifer recharge to parks, recreation and transportation. There were also large public meetings where thousands of area residents were invited to speak their minds. Frisinger organized and chaired most of the meetings.

The meetings attracted some NIMBY types, says Frisinger. "There were a few people who kept hoping we would find [environmental issues] that couldn’t be mitigated and that the whole thing could be shut down. But once they were reasonably assured that there would be no environmental harm done, they really liked the idea of having a neighborhood in which you could walk from place to place."

One of the first builders at Issaquah Highlands was Lozier Homes Corp. of Bellevue, Wash. The company had no experience with neotraditional communities but had been building on smaller lots for 15 years. "Prior to this, we were building on 4,500-square-foot lots at a time when the average lot size was 7,200," Lozier president Mike Levy says. "Higher densities are a way of life in the Puget Sound area now, not just at Issaquah Highlands but at every community."

Levy says the site design and amenities are above average for the market. Much attention is given to the placement of street trees and neighborhood greens. "In 20 years there will be this great canopy of trees going down all the streets," he says. "And they were the first [developers] that even talked about putting Category 5 wiring into the houses, let alone fiber-optics into the streets and up to the houses."

Architect Doug Dahlin of the Dahlin Group, San Ramon, Calif., designed the original master plan for Issaquah Highlands. After the project received final approval, Peter Calthorpe of Calthorpe Associates, Berkeley, Calif., fine-tuned the plan and designed other elements, such as the town center.

A total of 3,250 homes are planned, plus 425,000 square feet of retail space and 3.5 million square feet of office space, of which Microsoft will occupy 3 million. There will also be schools on the site. Groundbreaking occurred in 1996, and the developer began selling lots to builders at the end of 1997; to date, approximately 500 homes are built and sold. The mix includes single-family homes, townhouses, condominiums and rental apartments.

Because the Issaquah Highlands property was originally part of King County, a three-party agreement was created between Port Blakely, the city of Issaquah and the county "in which we spelled out who would be responsible for building certain portions of the infrastructure and how much money was going to be dedicated to building parks and recreational facilities," Frisinger says. "Then we wrote a two-party agreement between Port Blakely and the city that is overseen by a major development review team, which is a division of public works and engineering."

The team reviews the planning and permitting process, and as long as proposals are consistent with the agreement, permits are issued much faster. "The developer doesn’t have to go back to the planning department and negotiate anything," Frisinger says. "It’s a way to cut red tape and dedicate city planning and engineering resources for the large projects." Issaquah Highlands is the first urban village to be developed under such an agreement, which will remain in effect for 20 years.

City engineering standards were also modified to accommodate certain aspects of the site plan, such as the narrower streets. The local fire station will have a smaller engine that can handle the turning radius of the streets, she says.

Ultimately, the city re-established its UGB to include Issaquah Highlands. In return, the developer donated 1,400 of the site’s 2,223 acres for open space on the east, or rural, side. "We were allowed to develop 1 acre of new urban land for every 4 acres we donated," Kirk says. "That was a major compromise."

Reaction to Issaquah Highlands has been mostly positive, Kirk says. "The city is very happy about it. All the governmental agencies like it, and the general community likes it. The 1000 Friends of Washington sort of grudgingly accept it; they’ve never gotten over the [UGB] issue.

"There’s been a lot of growth out here, and there are small pockets of people that just don’t want anything," Kirk adds. "But most people feel that if growth is going to occur, this is the way they’d like it."

Rewriting the Rules of Suburbia:

Issaquah Highlands, Issaquah, Wash.

Also See:

Rewriting the Rules of Suburbia

Integrating Old and New

Three Years, 200 Open Meetings, One Vision

Charrette Builds Consensus for TND

Rewriting the Rules of Atlanta's Vast Suburbia

Rewriting Land-Use Rules in Lancaster County: Balancing Framing and Growth