Los Valles was to be a 500-acre master planned California community with an Arnold Palmer-designed golf course ringed by 210 generous lots, each more than an acre in size. That was before the recession. After the failed project was taken over by the real estate developer and investor, iStar, the Santa Clarita, Calif., development today is going through the final entitlement stage to become a community with 490 lots and no golf course. Instead, there will be urban gardens, pocket parks, trails, a citrus orchard, and a vineyard at the entry.

Ponte Vista, in San Pedro, Calif., indefinitely lingered after proposals by two developers stalled thanks to the housing market crash and opposition from neighbors. One pre-recession plan sought to build as many as 2,300 units on 61.5 acres of former U.S. Navy housing, including a midrise building that would have looked down on the neighborhood of single-family houses across the street.

iStar took over and proposed fewer than 700 units of traditional single-family homes, attached townhomes, and single- and multistory flats, which were inspired by market research and designs solicited from architects for local home builders to accommodate various Los Angeles buyers such as empty nesters, move-down buyers, and young families; buyers who all lacked available entry-level or move-up homes. With more green space to work with, the project, renamed Highpark, will offer dog parks, pocket parks, and trails, including one that will take hikers up 60 feet of topography to views of Los Angeles.

EMPHASIS ON THE EXPERIENCE

“The Great Recession, going on as long as it did, quite frankly gave us more time to sweat the details,” says Steve Magee, iStar’s executive vice president of land and a former Pulte and Centex vet. “Gone is the day when we were running a big inventory of lots, pouring a thousand slabs every December, and then the boss would look at me and say, ‘OK, where’s our next deal?’”

Master planned communities (MPC) then were high-velocity construction projects built when anything would sell and were synonymous with cookie-cutter architecture, golf courses, and tennis courts. Some developments were so massive and isolated that cars were a necessity for residents to be able to meet their basic daily needs. But today, savvy developers are being more deliberate about understanding their market and delivering greater green space, fewer hard amenities, and more diverse product.

“Master plans are a lot more experiential than they ever have been before,” says Ken Perlman, a principal with John Burns Real Estate Consulting. “You’re seeing people live their lives, and it’s less about stuff, having the biggest house, and the fanciest car. Now it’s about where are there great things to do and where can I be outdoors?”

If Shea Homes had planned Sage prior to 2007, the MPC probably would have had a clubhouse, pool, and little more. But now when the new Livermore, Calif., community is built out, there will not only be a pool and spa; residents also can stroll along an art walk with eight public sculptures, meditate at the yoga lawn, exercise on a fitness path that connects with the Livermore trail system, harvest vegetables from the community garden, prepare a harvest-to-table meal at the indoor/outdoor clubhouse, and relax afterward with neighbors beside the outdoor fireplace—all activities that don’t typically happen in an attached housing environment.

“When we trained our sales team, we wanted them to see that it’s less about selling the floor plan and home and is more about marketing the community and lifestyle that customers can buy into,” says Adam Hieb, vice president of sales and marketing for Shea’s Bay Area division. “There are only so many ways you can go with three bedrooms and two baths. The difference-maker is the amenities.”

NATURAL BEAUTY, SOFT AMENITIES

Walking trails are the No. 1 attraction among residents in every HHHunt community, according to surveys the developer/builder commissioned from John Burns Real Estate Consulting. “We put a lot of focus on trying to do paved walking trails meandering through common spaces to create those natural vistas that you already have in communities where you have environmentally sensitive areas to develop anyway,” says Jonathan Ridout, director of development for the Blacksburg, Va.-based developer and home builder. “So you may as well take advantage of them from an environmentally safe point of view.”

Toll Brothers is putting miles of trails into NorthGrove at Spring Creek, in Magnolia, Texas. Two hundred acres of the 600-acre MPC are being left as heavily wooded greenbelts. Golf courses are out, dog parks, a stargazing facility, and bird houses throughout the community are in. “We’re trying to work far more on natural beauty rather than man-made beauty,” says Jim Jenkins, vice president of master planned communities for Toll. “In many areas, instead of formal plantings, we’re now conducting reforestation efforts.”

Another attribute of post-recession community planning: soft amenities. Toll Brothers’ club house at NorthGrove is an open-air building with window walls that open to the outdoors and the resort-style pool. Rather than packing the building with stuff, the center is conducive to entertaining at events such as wine tastings and food-sampling gatherings. “Years ago you wouldn’t have found a coffee machine in a recreation center, but now we wouldn’t build a rec center without a fairly elaborate one,” Jenkins says.

HHHunt has activity directors on its community staff who organize six large-scale programs—that’s up from organizing a single event a couple of years ago—per year per community to engage residents. Programs include a summer concert series and fall festivals, with live entertainment, food, and beer trucks, held on an athletic field or open lawn. Once a month, HHHunt brings in ice cream trucks to give away free frozen treats.

Determining the mix of open space and housing is a tricky business, particularly since the cost of land has increased 16 percent since 2009. Yet, consider that The Pinehills, in Plymouth, Mass., only builds on 30 percent of its 3,174 acres. But the community, if it was its own town, would be 9th among the 25 towns in Boston’s South Shore market in terms of residential sales volume and 4th in terms of price, even though more than 50 percent of the MPC’s housing is attached product, including a midrise apartment building and independent living, assisted living, and memory care housing where more than half of the seniors are the parents of Pinehills residents.

“The real trick is to be able to figure out how to add more green space and not lose any density,” says Tony Green, The Pinehills’ managing partner. “Part of that is having a really wide range of housing types, which was part of our plan from the beginning. If we were going to grab enough market share, we had to spread our wings very wide.”

SEGMENTATION AS A GROWTH STRATEGY

Edward R. James Companies was a builder for both phases of a former naval air station that was developed by the Village of Glenview, an affluent Chicago suburb. The company started the first phase in 1999 and built 299 luxury single-family homes in a golf course community called Southgate at the Glen. Before proceeding two years ago with the adjacent Westgate at the Glen, the village stipulated that it didn’t want detached single-family, so as not to overwhelm the public school system. However, “We can’t just throw 300 of the same units like townhomes, rowhouses, or condos in there,” says Jerry James, president of Edward R. James. “That would overwhelm the market, so we decided to segment this property.”

The builder proposed a segmentation strategy to appeal to a broader customer base, with about 60 units each of five different products: rowhomes for older buyers, clusters of single-family zero lot-line homes for buyers looking to downsize, and three townhouse styles. The mix made for quicker absorption and gave the builder leverage to price some homes at a premium because there was less of each type to sell. Some customers who bought a three-bedroom Southgate house have traded down to a smaller home in Westgate, which is about 80 percent sold.

“The segmentation strategy is the smart play; it’s just like the stock market,” James says. “If I buy big on one stock, I can win big if it goes up and lose big when it goes down. But if I have multiple product types to sell over a period of time, I have more than a one trick pony to ride in response to market demand.”

Real estate advisor RCLCO noted in its 2015 ranking of the top-selling MPCs that the communities that provided product segmentation increased home sales. Still, segmentation can be tough to pull off because community residents perceive attached products, especially rentals, as inferior and detrimental to property values and the character of the community. Another obstacle is the cost of land.

“In markets where the land is difficult to build on or is very expensive, that dictates the lowest price point you can get to, and then you essentially are having to deliver product that’s higher priced and only appealing to higher-income buyers. You can’t get volume in an environment like that,” says Todd LaRue, an RCLCO managing director.

When The Pinehills management proposed offering apartments from Avalon Bay, homeowners complained. During a community forum, a recently widowed middle-age homeowner put a face on the need for rental there. She told her neighbors that she loved her community but didn’t want to live alone in her big house. Their opposition would exclude her from the neighborhood. The homeowners relented, and management has since opened Hanover at The Pinehills, its second apartment complex.

IN PRODUCT DIVERSITY LIES STABILITY

Green says that homeowners tend to perceive townhouses and apartments as low-quality structures, so they need to see that that kind of housing, done right, can be high value. He adds that 5 percent of the community’s buyers last year were renters who were trying out The Pinehills.

Yet, even if housing diversity and density are assuming a bigger role, MPCs still have a dearth of affordable homes and rentals. There are notable exceptions, such as the starter homes selling for as low as $182,000 built by Holmes Homes at Daybreak, the largest MPC in Utah, which was developed by Rio Tinto Kennecott. But MPCs with affordable homes tend to be in private/public development partnerships with a municipality or a public housing authority. Elsewhere, the rising cost of land has pushed up home prices and, combined with a shrinking middle class, the home building industry has focused on providing for affluent buyers.

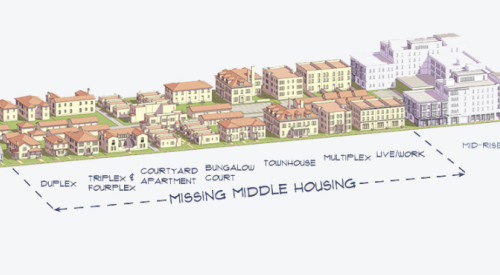

The industry used to build more duplexes, fourplexes, bungalow courts, and housing types with seven to 20 units per acre. The share of these attached products, which would be more attainable for young families, first-time buyers, and middle-income households, has substantially declined over the last several decades, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures. Daniel Parolek, principal with Opticos Design, a Berkeley, Calif., architectural and urban planning firm, says that developers and builders would do well to satisfy an unmet need in the market for “missing middle housing” for middle-income households.

“We’re getting more and more calls from builders saying: We’ve historically built mostly single-family; we dabbled in townhouses, but we can’t even build our townhouses for a price that a lot of people can afford. What is a product that we can introduce?” Parolek says. “I think what is a big challenge with the middle in these master planned communities is who’s going to build them? Multifamily builders want volume and bigger complexes so they can be efficiently managed. Single-family builders are allergic to anything that is stacked. One of the challenges right now is that there are so few builders out there that are geared to build these housing types, especially in the master planned community context.”