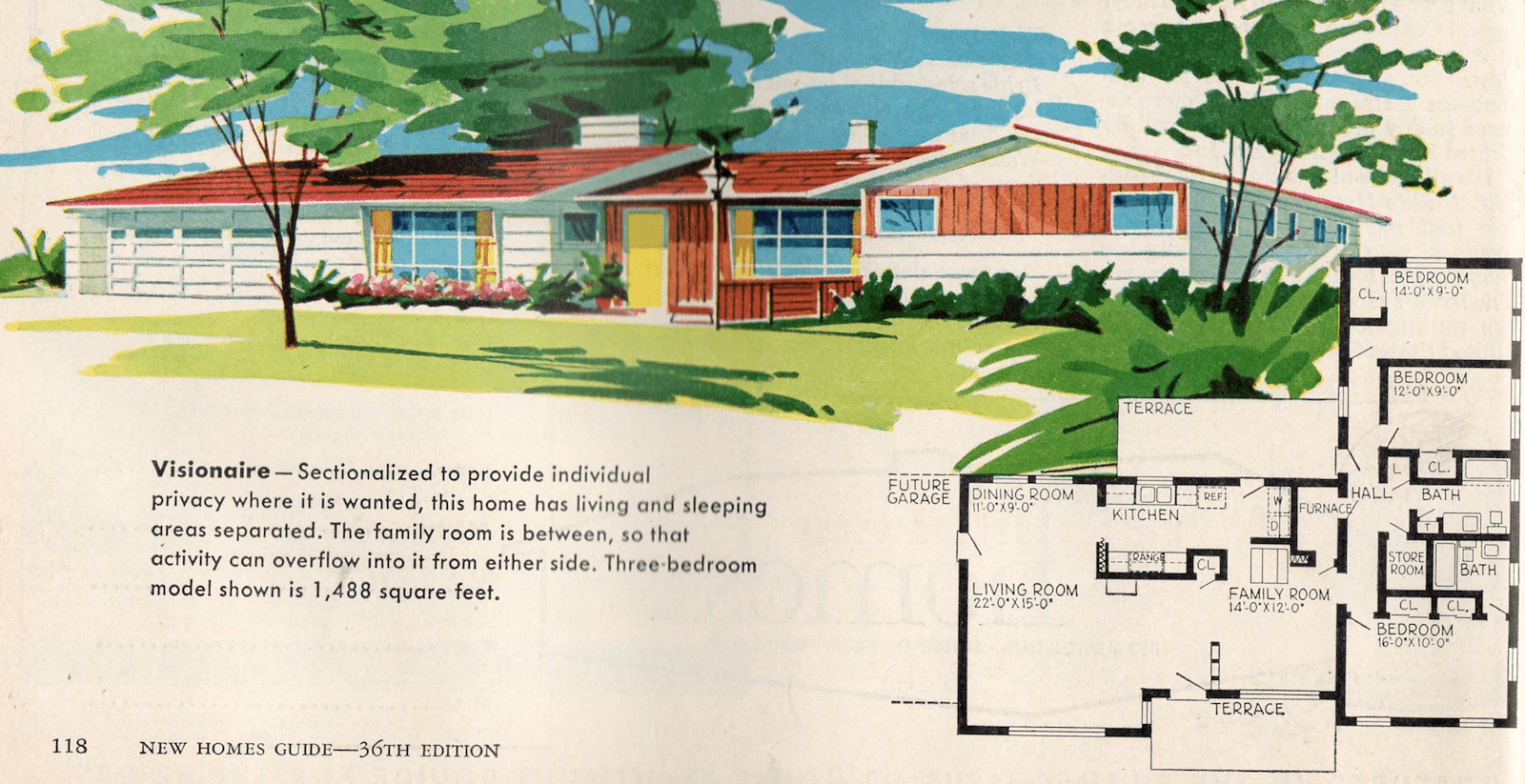

In 1962, with my older sister on the way, my parents bought a 1,400-square-foot, three-bedroom, two-bath, single-level ranch house with a living and dining room, galley kitchen, and a two-car garage. Nothing special; your basic postwar suburban home. They raised three kids there, transitioned to being empty nesters and then retirees before selling the house 50 years later—a full life cycle of use. The only structural change they made was a modest family room and den addition in year 12.

So when I hear that the standard 3-and-2 suburban house no longer suits today’s buyers, and that builders need to think (and build) outside that box, I bristle a little … until I expand my thinking beyond my own childhood experience to consider the demographic, employment, economic, and societal shifts that have occurred since then to alter our industry’s approach to providing shelter that meets today’s far more diverse definition of a household.

RELATED

- Rethinking Housing Design in 2023

- Living Now: America at Home Study Concept Home

- On-the-Boards Designs for Today's Homebuyer

Designing Homes for Changing Buyer Needs

Consider the rise of multigenerational housing. As of March 2021, the most recent data available, nearly 60 million people in the U.S. (or 18% of the entire population) lived with multiple generations under one roof, according to Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. That’s four times more than it was in the 1970s. Pew also reports that 25% of U.S. adults aged 25 to 34 resided in a multigenerational family household in 2021, up from just 9% 50 years ago. Chances are, those trends will continue.

Or the fact that 58% of new single-family homes sold in 2021 were two stories or more, a script flip from 33% in 1973. With that, the average square footage of a new home has ballooned from 1,660 square feet in 1973 to 2,486 in 2022. Those stats indicate the impact of declining availability and rising costs of land that have pushed homes upward to get more space while making it more difficult to age in place like my folks did.

But those dynamics don’t have to be at loggerheads if you tweak your product a bit. I won’t advocate for elevators, but ground-floor primary suites and pocket offices, as well as accessory dwelling units (where allowed), can go a long way toward making a multilevel house livable for multiple and aging generations. And if your buyers aren’t ready for that, such spaces can be flexible—a guest suite, a playroom, or a larger office—until different lifestyle needs arise. Wider hallways and doorways, while eating up some footage, also help, as do hard-surface floor finishes and zero-threshold showers and room transitions.

There’s a reason why the average homeowner moves every eight years, on average, and it’s not always to cash in on appreciation but often because their current house no longer meets their needs. Maybe that’s a form of planned obsolescence, but I think it’s also an opportunity for builders to distinguish themselves in an increasingly competitive market by providing homes for a lifetime of living.