About 25 years ago, I sat in a classroom at an EEBA (Energy & Environmental Building Alliance) conference listening to Mark LaLiberte’s presentation, “Cure for the Common Callback.” Among many building science jewels he imparted that day, what Mark drove into my fertile mind was the (now) well-worn but still true mantra: “Build tight and ventilate right.”

That principle has stood the test of time, but so has the common rebuttal, “Houses have to breathe!”

That rebuttal is wrong, but some people still consider it common sense.

It’s not. People spouting the “homes need to breathe” cliché equate breathing with passive air leakage and the belief that air leaks keep structural systems from absorbing and retaining moisture that can lead to myriad problems.

Drying vs. Airflow for Wall Assemblies

Understanding the difference between Mark’s mantra and its rebuttal requires critical thinking. For me, it took a bit longer to wrap my head around the fact that airflow doesn’t do the same thing as diffusion through vapor permeability.

The truth is that while walls do need to be able to dry out, drying doesn’t require airflow. Rather, it requires well-designed, vapor-permeable wall assemblies. If you detail those assemblies correctly, moisture can escape through a wall without the aid of airflow. In short, you can build an airtight box that still allows moisture vapor to pass through.

The Basics of Indoor Air Quality for Homes

But while buildings don’t need to breathe, people do. The ideal in a modern-day home is to provide clean indoor air via an intentional, regulated air path. You can only create regulated airflow with mechanical equipment—namely, your HVAC system—and operable windows. Intentionally building an unregulated, leaky building to provide ventilation, healthy indoor air, and comfort is like managing your personal finances through bingo or the lottery. It’s a gamble, and it comes with inherent risks, such as:

1] The air will be contaminated with whatever it picks up along the way (read: stuff we don’t want in our lungs).

2] Warm, moisture-laden air will cool off in the wrong places, such as inside wall cavities, and will condense on cool surfaces. Studies show that far more moisture can be introduced into building assemblies by air leakage than by diffusion.

3] Airflow will carry heat in or out of the building, usually at the least desirable times.

These reasons, along with the need to prevent the spread of fire, are why you want to seal every potential air leak path between the exterior and the conditioned space of your homes, as well as decouple interstitial cavity connections, such as duct chases, within the building enclosure. (Fireblocking also prevents these cavities from carrying moisture-laden air from warm to cool parts of the home.)

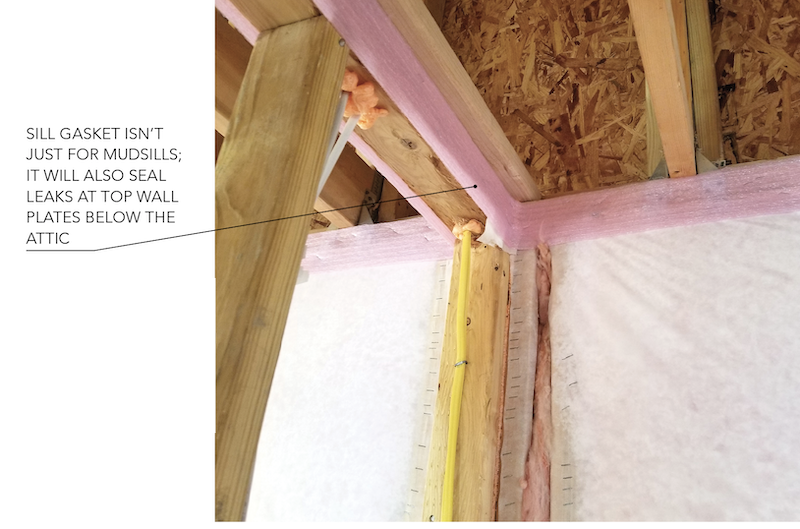

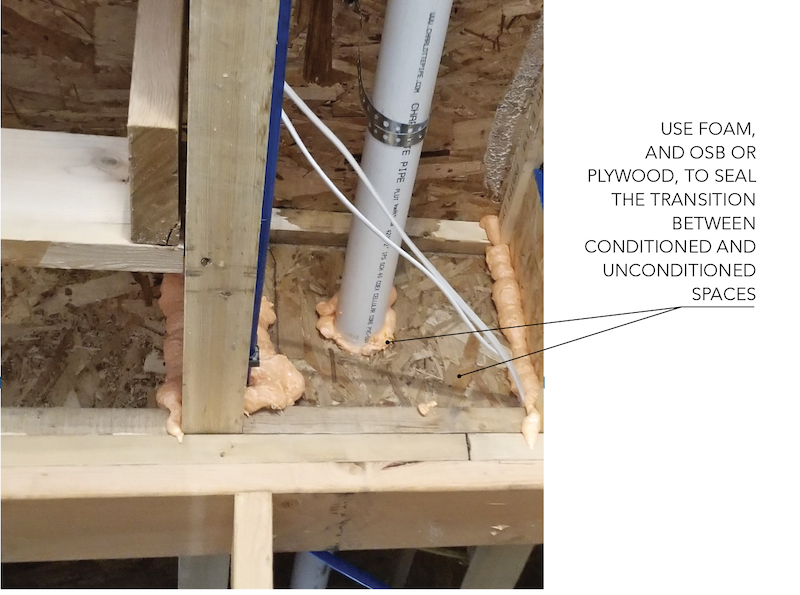

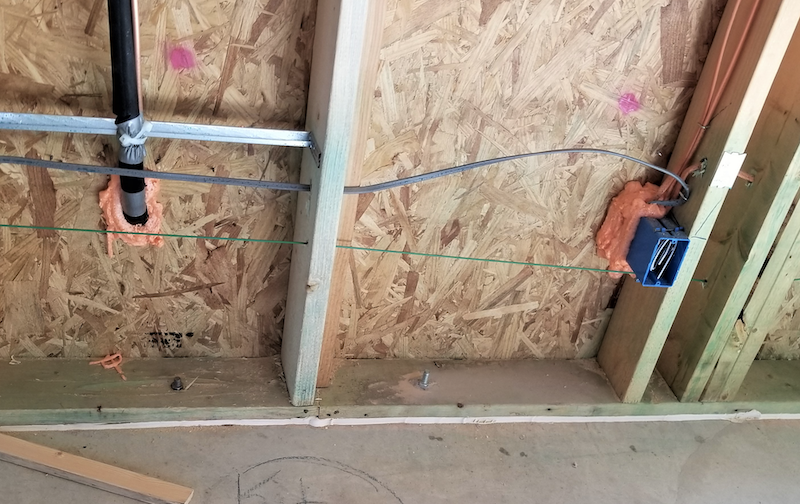

Exterior walls, as well as ceilings below ventilated attics, should be made as airtight as possible. Interior walls, plate penetrations, drop soffits, and connections with both conditioned and unconditioned basements should be air-sealed.

To achieve such airtightness, blocking, caulking, and spray foams are your friends. Don’t rely on “chinking” with fiberglass batting—it’s a filter, not an air barrier. Fire-rated caulks and foams that seal between floors and the attic space are required by many jurisdictions and are a best practice everywhere.

When combined with proper ventilation, air sealing to achieve a very tight home improves indoor air quality, reduces the potential for moisture damage in building assemblies, and enhances energy performance. Remember: Build tight and ventilate right!

Graham Davis drives quality and performance in home building as a building performance specialist on the PERFORM Builder Solutions team at IBACOS.

Read more on Pro Builder

Read more about tight homes and ventilation on our sister site, ProTradeCraft.com:

- Tight Houses, Blower Doors and Ventilation Explained in Under 3 Minutes

- The What, Why, Where, and How of Blower Door Testing

- Air Sealing Details for a Net Zero Energy Home

- Air Seal Wall Sheathing to the Foundation

Access a PDF of this article in Professional Builder's December 2019 digital edition