In January 2014, the Wall Street Journal ran an article called “Looking for a New Old House?” which addressed Americans’ desire for new homes that look historic on the outside but feature modern floor plans and amenities on the inside. The New Old House movement isn’t new. According to Middleburg, Va., architect Russell Versaci, it dates back to the early 1980s when homebuyers grew disenchanted with tract-house subdivisions.

“There was a real longing for something more interesting and richer in lifestyle, texture, and associations,” Versaci says. As McMansions proliferated in the 1990s, he began to hear the complaint, “These houses are out of hand. It’s like a supersized trophy house that says nothing about us. It’s a lot of vacuous space, and it never feels like home.”

A Movement Emerges

The backlash drove Versaci to develop the New Old House. “I wasn’t the first to use the term, but I was the first to create an architectural movement around the idea, starting with the beginnings of my practice in 1985,” he says.

Today, a select group of architects and builders specialize in the New Old House. Horizon Builders of Crofton, Md., does custom versions in the Washington, D.C., area ranging from $5 million to $40 million.

“People are looking for new homes that have a classic type of design,” says George Fritz, Horizon’s chief operating officer. “A lot of our clients are looking at legacy houses they can pass down to the next generation. They’re planning on building it once and building it well so it’s sustainable and the maintenance can be easily tracked and managed.”

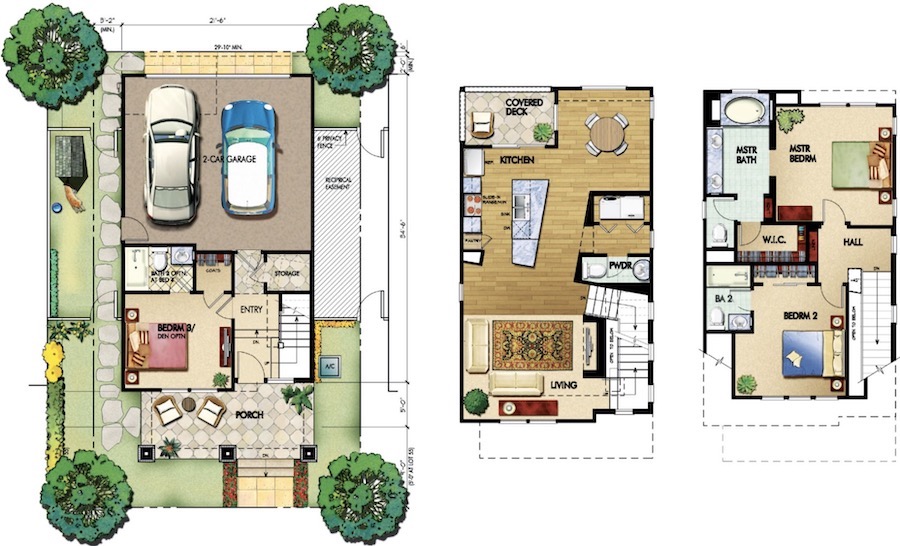

Production builders offer the New Old House at lower price points. Infill specialist Classic Communities of Palo Alto, Calif., recently completed the Classics at Station 361 in Mountain View, Calif. The single-family house styles include Shingle, Arts and Crafts, Spanish, Craftsman, and Bay Traditional, while the townhomes are either Spanish or Mission style. The builder worked with Dahlin Group Architecture, Pleasanton, Calif., taking cues from neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay area where the homes date back to the 1920s and 1930s.

Dallas-based Darling Homes has a foothold in the New Old House concept with its American Classic Series. David Mathews, vice president of product development, says the company has sold close to 400 homes since the series was introduced in 1997. Depending on location, the homes range from the mid-$200,000s to the mid-$400,000s.

“The person who buys these homes is typically a bit more affluent and more of a risk taker,” Mathews says. “In fact, [the American Classic Series] doesn’t necessarily attract a lot of engineers and accountants. It attracts a lot of entrepreneurs and designers and people who are more fashion-oriented.” Buyers range from singles and young couples to older families and empty nesters.

A Balance of Yin and Yang

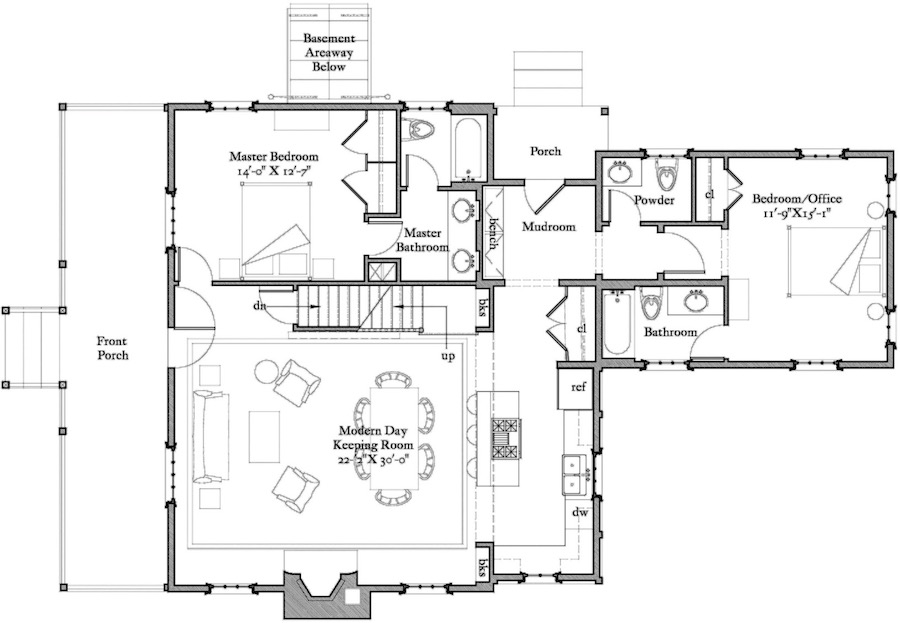

Versaci emphasizes that the New Old House is not a replica. “You don’t have to dress it in period costume to make it work for you,” he says. “The house has to have authentic historical characteristics, but it needs to be reconfigured for the way we live today.” Since old houses didn’t have family rooms or eat-in kitchens, architects must develop creative solutions that work within the New Old House fabric.

George Fritz, chief operating officer for Horizon Builders, Crofton, Md., adds, “You need an architect that understands the massing and the detailing and the relationships between the different pieces of trim on the exterior.”

It’s important to incorporate elements that are emblematic of the classic style on which the house is based. “For example, a Dutch Colonial is not a Dutch Colonial unless it has a gambrel roof,” Versaci says. “A Georgian house is nothing if it’s not completely symmetrical, with a center door and equal groups of windows on either side. It also needs to have a very strong classical portico or entry feature in its center. At the same time, it’s a kit of parts that the designer can use to create a new interpretation of that style.”

He recently designed a 2,800-square-foot Virginia Tidewater farmhouse that is built along the lines of a classic Colonial Williamsburg house. “I had to figure out how to make the plan much more open and add a guest bedroom suite. I also had to determine where to put the kitchen, because Colonial Williamsburg houses never had kitchens.”

Versaci housed the kitchen in what looks like a formerly open porch on the side of the house, subsequently enclosed with walls. “You can still see the column posts and it’s still shaped like a porch,” he says. “The guest bedroom suite looks like an old outbuilding that’s now attached to the main house by a breezeway.”

Building for the 10 Percent

Darling Homes’ Mathews estimates that the American Classic Series accounts for 10 percent of the company’s total production. “We’re higher in price than comparable standard product, but we’ve really tried to stay true to the vision we were trying to deliver,” he says.

When Mathews toured other builders’ homes around the country, he noticed that although the exteriors might suggest a New Old House, the interiors didn’t. “We changed up our trim detail, our stair parts, and our kitchen cabinets, and put in period-style fireplaces. The interior complemented what buyers saw from the street.”

Darling refined its process so that the homes could be produced consistently and effectively. “We trained our suppliers, trades, and construction managers to execute what we envisioned,” Mathews says. “We copied a lot of details from historical styles, at the same time keeping the economics of the project in check in order to hit the right market price. Consequently, there’s not a lot of difference from house to house on some of the details.”

Currently there are seven floor plans in the series, each with three different elevations. They range from 2,150 to 3,500 square feet. The builder initially worked with Addison, Texas, architecture firm Gary/Ragsdale, but the design work is now handled entirely in-house.

Unlike the brick and stone elevations typical of the Dallas market, the American Classic Series exhibits Craftsman and Victorian influences. The homes have masonry wainscots around the bottom, but the siding is painted. The covered front porches have columns set in brick or stone, and the interiors feature transom windows, interior beadboard finishes, crown molding, and built-in bookshelves.

Courting Silicon Valley Buyers

Classic Communities is tugging at the heartstrings of Silicon Valley buyers with its latest homage to old California, the Classics at Station 361. The Mountain View community opened in June 2013. To date, 41 of 65 homes are sold at prices ranging from $1 million to more than $1.5 million, says Scott Ward, project/development manager.

Ward says part of the community’s appeal is its proximity to downtown Mountain View and public transportation. Station 361 is also low in density (about 15 DUA) compared to the apartments along the San Francisco peninsula rail corridor.

But buyers also recognize that few neighborhoods with any design integrity remain in California. “We’re delivering a product that some people identify as emblematic of an historic period in Mountain View,” Ward says.

“Those old neighborhoods are very eclectic—Spanish, Shingle, cottage,” adds John Thatch, senior principal at Dahlin Group. “We took that as our inspiration.”

So in what type of area does the New Old House fit? Ward says it not only works well in an infill context but would also be appropriate in a larger-scale, New Urbanist context.

“Many of the original New Urbanist communities traded on that,” he says. “It’s turning the clock back a little bit. The architecture reinforces the pedestrian-friendly, small-town attributes that people romanticize.”

Reinventing Traditional Design

Architect Russell Versaci developed his “Eight Pillars of Traditional Design” as a blueprint for home builders and designers who want to create the New Old House:

- Invent within the rules

- Respect the character of the place

- Tell a story over time

- Build for the ages

- Detail for authenticity

- Craft with natural materials

- Create the patina of age

- Incorporate modern conveniences

The first pillar (invent within the rules), acknowledges that every traditional style is recorded in a common set of rules that shape the outline of the house, govern the appropriate materials to use, and determine the way the details go together.

“You can create a new design by inventing a clever plan arrangement or a distinctive detail that pushes traditional forms in a new direction,” Versaci says.

While he advocates the use of natural materials such as fieldstone for walls and heart pine for floors, Versaci is, ironically, a big proponent of synthetic materials such as stone, fiber-cement siding, and PVC moldings. But he cautions that while synthetics can be extremely durable, there’s not a lot of money to be saved by using them.

“It’s about the long-term amortization of costs, because you don’t have to do a lot of painting or tearing out and replacing,” Versaci says.

Practicality must complement authenticity, notes John Thatch of the Dahlin Group. “We want to make sure the money is wisely spent,” Thatch says. “We’ll make the side and rear elevations simpler as long as we can still pull off the character. It might mean squaring up the plans and the rooflines in some places, and simplifying masonry or shingles or eave details.” Like Versaci, Thatch believes newer building materials such as composite siding are better than their natural counterparts. “The different plaster chips and additives actually get closer to what was done in the past. They’re more dimensionally stable and don’t crack.”