In many markets across the country, land and construction costs are pushing home builders toward higher density housing forms to keep home prices affordable for entry-level buyers. But the townhouses and duplexes that achieve densities above seven units to the acre often cram residents together so closely that privacy — and even security — are compromised.

We asked two of the nation's top practitioners of high-density design — Colorado land planner David Clinger and Scott R. Adams, senior principal of Southern California's Bassenian/Lagoni Architects — how to create townhouse and duplex neighborhoods that achieve both affordable pricing and privacy protection. Here's what they showed us.

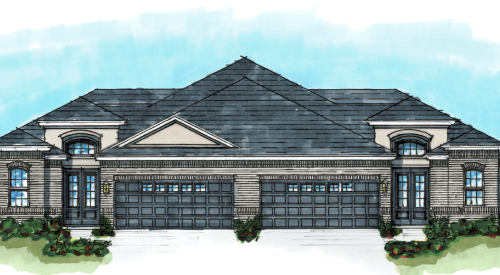

Varied rooflines, porches and balconies disguise the three-story nature of Centex's Citrus Commons townhouses in Chino, Calif. The development has 18 units per acre. |

Denver-based land planner David Clinger points out that housing development never happens in a perfect world where builders produce what the market demands. Local politicians, planners and neighbors are involved.

"Right now, planners and politicians are in love with Traditional Neighborhood Design," Clinger says, "but it's hard to get densities up and prices down in rear-loaded TND neighborhoods. Moreover, when the garage is at the back of the home, it's hard to fashion a back yard that's big enough to be useable or relates well to the adjacent interior spaces. And the front and side yards are anything but private."

Clinger came up with what he calls an "un-plex" to marry higher density to lower prices in TND homes that each have three useable, private outdoor spaces that make the adjacent indoor spaces in the home more pleasant and more functional.

"The un-plex is a detached home when viewed from the public street in a rear-loaded, traditional design community," Clinger says, "but it becomes a duplex — and qualifies for duplex zoning — by attaching the garages at the rear of the homes. This solves a big privacy problem common to duplexes. There's no shared wall in a living space, so there's no sound transmission. The residents experience living in detached homes. And by pushing the two garages together at the back of the homes, we create larger back yards, concentrating that space where it relates well to the adjacent interior space — and using the mass of the house and garage to screen it from neighbors' view on two sides. "

Although the lot line runs along the common wall of the garages and down the middle of the 10-foot space between the sides of the duplex, Clinger turns that space into a private side courtyard.

Every home in Clinger's concept has one blank wall and one that opens with windows and sliding glass doors to a private side courtyard that expands the indoor space visually and functionally. At the front of the home, Clinger uses the standard design element for TND communities — a 6-foot-deep front porch that is both a semi-private, social space relating conversationally to the front sidewalk and a privacy buffer for the interior living space behind it, at the front of the home. Wrought iron fencing with a gate and landscaping shield the side yards from the street in front.

Clinger says un-plexes can be built to densities ranging from seven to nine units per acre. "The lots in a suburban location would be 40 feet by 100 feet, with two parking spaces behind each garage," he says. "On high-priced, infill sites, we might eliminate the parking behind the garage and rely on the public street out front for guest parking. That would reduce lot size to 40 feet by 80 feet and boost the density to nine units per acre.

"At densities in this range, the biggest privacy compromises usually occur rear-to-rear," Clinger notes. "But with each side of a 20-foot alley right-of-way buffered by two-car garages ... distance is the best privacy protector."

The un-plex concept is now underway in eight projects around the country.

Solving a California QuandaryCalifornia politicians and planners want rear-loaded townhouses with front doors facing the public street. That's a tough nut in a state where the car is king and the public street may be a collector with 50 mph traffic and no pedestrians. But the Left Coast is also home to many of America's top housing designers — who are proving they're up to the challenge.

Density specialists Bassenian/Lagoni lead the way. Adams, who heads that firm's land planning operations, says a skyward movement of bedrooms in Orange County and the Inland Empire is actually promoting privacy in the latest generation of Southern California townhouses.

"Many builders are taking their housing forms vertical to get more square footage in a smaller footprint," Adams notes. "We even see it in detached homes, but especially in attached — so a two-story townhouse becomes three stories, or even four. But that's actually creating some privacy benefits because those third stories are usually bedroom space, and that verticality actually creates more isolation for a bedroom. But if you really want rear-loaded townhouses at 18 to the acre that don't have privacy problems, you have to be careful not only with the relationship of one building to the next, but with the way window patterns relate to each other — and even the way individual rooms relate to others in the same building."

As an example of this new generation of more vertical townhouses, Adams offers Citrus Commons, an 118-unit, rear-loaded, three-story townhouse community of five- and seven-plex buildings that Bassenian/Lagoni designed for a 6.64-acre site in the Inland Empire. Centex Homes opened models in February this year. It's in the master-planned community of The Preserve at Chino, just outside Orange County. Young couples are snapping them up. Even in the midst of a widespread slowdown in sales, this product sells at a rate of two to three a week (gross), at prices ranging from $375,228 to $431,900 for two-bedroom townhouses between 1,530 and 1,603 square feet.

"If you look at the three levels of these townhouse buildings, you see that the first level is fairly busy," Adams notes. Every home has a private entry and private garage access, and the upper floors have more carve-away niches for porches and more partial roof areas.

The most interesting plan of three carved into the seven-plex buildings is Plan 2, which is only 12 feet, 8 inches wide on the first floor — just wide enough for a private entry foyer and laundry room in front and a tandem two-car garage at the back. But at the second floor, this plan widens at the back of the building into spaces located above the first-floor garages of Plans 1 and 3. That main living level also has a private, outdoor balcony on the corner of the building, above the garage of Plan 3. The master suite is on the third floor, far above the mad world below.

It should not surprise that this is the best-selling plan at Citrus Commons because it carries the lowest price tag, starting at $375,228 for 1,530 square feet. But Centex vice president of sales Carola Cherief says buyers also love the youthful, urban, loft-like feel of the plan, and they are especially responsive to the private balcony.

The pedestrian paseo, at the center of the Citrus commons site plan allows interior buildings to face an active, social setting. |

Builders across America should pay attention to this trend toward verticality in townhouses that is just beginning on the West Coast. Adams sees four stories on the horizon in California.

"We are now seeing more and more use of private residential elevators," Adams notes. They're expensive, he says, but on pricey infill sites, where townhouses may be targeted to empty nesters, an elevator could make very private spaces in the sky a hot seller.