(Editor’s note: This is the first of a series of a articles we’ll run each month during this millennium year, building on the theme of PB’s January cover feature. For that story, we asked top builders and consultants across the country to advise a young, but seasoned pro starting a new home building business this year. We came up with a list of dos and don’ts that could mean the difference between success and failure in this new era, where everything seems to change faster than ever before.)

It’s a growing market, yet one that limits competitive exposure. You’re not likely to find the big public builders doing tear-downs in the inner city.

The experience of Denver newcomer Scott Axelrod, 37, may be a lightning rod for others. When he decided to build houses for a living in his new home town, Axelrod was venturing way beyond his experience, but he did a lot of things right. Perhaps most important, he picked the right location and the right product. "My background was in athletic clubs," Scott says. "I had a downtown athletic club in Hawaii and a tennis club in Los Angeles. Then we moved to Denver from Hawaii to get better health care for my five-year-old daughter, who is diabetic."

"I’d invested in community development in the past, but never built homes. Because it was all new to me, I was willing to limit my upside if I also limited my risk, so I raised a ton of capital specifically for my first venture." And for that first project, Axelrod chose to build upscale homes on an infill site in Denver’s old, gentrifying, high-demand, and very posh Cherry Creek neighborhood. It was a smart move. A similar one might be available somewhere in just about every housing market in America.

Buyers of every age and description are tired of spending time stuck in traffic, and that’s especially true of aging baby-boomers. Now that their nests are emptying, many boomers face a mid-life crisis where they are suddenly more interested in making whoopee than watching the grass grow around their suburban homes.

As a result, there’s a budding movement of boomers heading back to the city, where they seek out gentrifying old neighborhoods that offer the opportunity to leave the car at home and walk to coffee shops, book stores, theaters, restaurants, and bars (youth is wasted on the young). Cherry Creek is just such a neighborhood.

Axelrod kept his start-up home building operation lean, with an office in his home. He contracted with an experienced home builder to teach him the sticks-and-bricks side by serving as his construction manager. He listed his houses with a Realtor rather than take on an in-house sales person. And he got the right price on his chosen site. "I saw it during my first two weeks in town," recalls Axelrod. "A 22,000 square foot lot where they’d already removed the house."

Axelrod built three houses on the site, ranging from just over 6000 to nearly 8200 square feet. He sold all three last summer, for nearly $2 million in revenue. And he returned 27% to his equity investors--not bad for a novice.

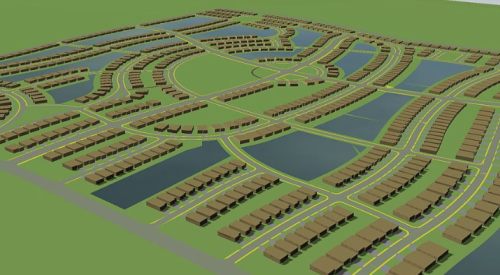

| Vancouver, B.C., is a hotbed of urban infill redevelopment. Shown here is a streetscape in Morningside, a 96-unit Omni Pacific project in the old, established bedroom community of Pitt Meadows. The detached homes on "pocket lots," designed by Bassenian/Lagoni Architects of Newport Beach, Calif., reach a density of nearly 10 units per acre. |

Tearing down small, older homes, built three or four units to the acre, to build more luxurious houses, at much higher densities, is the dominant modus operandi in Cherry Creek. It’s a strategy that will work elsewhere. And it’s not necessarily limited to small-scale operations like Axelrod’s.

On the West Coast, from San Diego to Vancouver, the infill redevelopment niche has become very specialized, but also incredibly profitable. And big business. For example, Olson Co. of California delivered 250 units last year, for over $60 million in revenue. "We’ll do over 500 units this year," says Olson vice chairman Sherm Harmer.

"As California continues to grow at a rate of over 400,000 new jobs a year, the cost of land, infrastructure, and housing in distant ex-urban developments is getting very high, especially in relation to the quality of life those locations can deliver. More and more people now see the prospect of living in established communities as increasingly attractive."

Harmer differentiates the urban redevelopment Olson does from infill housing on passed-over suburban sites. "We do re-urbanization. We’ve established relationships with about 35 cities and redevelopment agencies up and down the coast. We create solutions for them that in some cases take densities from 4-1/2 units per acre to 80."

Half of Olson’s projects are attached, half are high-density single-family. "We get single-family densities as high as ten units per acre," he says.

While he is enthusiastic about the potential of redevelopment in other markets, he also cautions that it is a high-risk business that calls for patient money on the front end. "The land acquisition and entitlements processes can take a long time," Harmer warns. "It’s very political. Most of what we do involves public/private partnerships. "And you’ve got to make sure the people on the public side understand that creating housing close to workplaces is not enough. The city has to actively rejuvenate a real urban lifestyle. Close to play is more important than close to work. The ideal is an urban setting that allows people to live, work, play, shop, and learn downtown."

A major stumbling block Harmer often runs into is archaic infrastructure, especially wiring. "We usually want a commitment from the city to bring fiber-optics or some other form of utility improvement that allows high-speed modem connections for work-at-home offices," says Harmer. "When people move back into the city, we find 40% of buyers have at least one person using the home as a full-time office."

Scott Ward of Classic Communities, a northern California specialist in the redevelopment of existing neighborhoods in established Silicon Valley cities like Palo Alto and San Jose, advises new infill practitioners to seek neighborhoods built in the 1950s to a density of four units per acre. Knock down those houses, he suggests, and rebuild in 1920s architectural styles, which are now much more highly valued. Classic did it in 1999 to the tune of $50 million for 125 units.

"The new urbanists have brought those 1920s styles back into vogue," says Ward. "We’ve just finished a 60-unit infill in San Jose, where our houses are 12-1/2 to the acre and sold for over $300,000 each, and a 33-unit project in Menlo Park, at nine to the acre, where prices ran from $650,000 to $750,000. Now we’re opening a 26-unit townhouse development in Palo Alto at 17 to the acre. The great thing about the California bungalow and Craftsman styles that we emulate is that they lend themselves to much higher densities. They built on very small lots in the 1920s and 1930s."

Like Harmer, however, Ward warns that these new city folks want modern lifestyles married to nostalgic architecture and neighborhoods. "Outside, they may look like the 1920s, but inside we have to be state-of-the-art modern. After all, this is Silicon Valley."

California architect and planner Aram Bassenian is a specialist in designing such projects. To get densities up without sacrificing nostalgic architecture, and keep the neighborhood pedestrian-friendly without asking buyers to give up any of their cars, is no mean feat. Then add the necessity for the homes to have all the electronic capabilities for a Roaring 2000s lifestyle.

"It’s changing our designs dramatically," says Bassenian. "But urban infill redevelopment offers builders the opportunity to be part of a solution to the perceived problems of growth and sprawl, rather than part of the problem. Why beat your head against a wall trying to get projects approved in the high-growth suburbs, where everyone seems to oppose you? In the city and in old established suburbs, the planners and politicians see redevelopment as a very positive force."